Torpedo Marmorata

– Marbled Electric Ray –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Data Deficient (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

| Scientific classification |

Torpedo marmorata

A. Risso, 1810

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Torpediniformes |

| Family: | Torpedinidae |

| Genus: | Torpedo |

| Species: | T. marmorata |

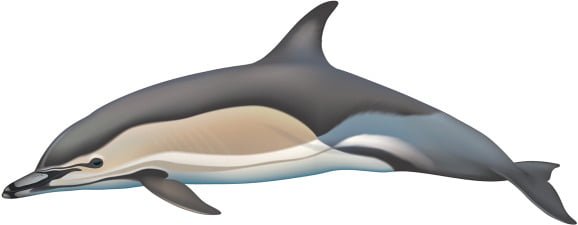

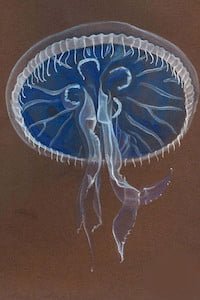

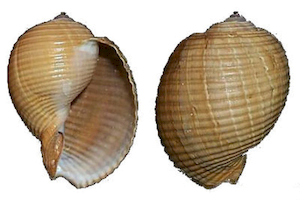

The marbled electric ray (Torpedo marmorata) is a species of electric ray in the family Torpedinidae found in the coastal waters of the eastern Atlantic Ocean from the North Sea to South Africa. This benthic fish inhabits rocky reefs, seagrass beds, and sandy and muddy flats in shallow to moderately deep waters. It can survive in environments with very little dissolved oxygen, such as tidal pools. The marbled electric ray has a nearly circular pectoral fin disc and a muscular tail that bears two dorsal fins of nearly equal size and a large caudal fin. It can be identified by the long, finger-like projections on the rims of its spiracles, as well as by its dark brown mottled color pattern, though some individuals are plain-colored. Males and females typically reach 36–38 cm (14–15 in) and 55–61 cm (22–24 in) long respectively.

Nocturnal and solitary, the marbled electric ray can often be found lying the sea floor buried except for its eyes and spiracles. This slow-moving predator feeds almost exclusively on small bony fishes, which it ambushes from the bottom and subdues with strong electric bursts. It defends itself by turning towards the threat, swimming in a loop, or curling up with its underside facing outward, while emitting electric shocks to drive off the prospective predator. Its paired electric organs are capable of producing 70–80 volts of electricity. This species is aplacental viviparous, with the developing embryos sustained by yolk and histotroph (“uterine milk”) produced by the mother. Mating takes place from November to January, and females bear litters of 3–32 pups every other year after a gestation period of 9–12 months. The newborn ray is immediately capable of using electricity to hunt.

The electric shock delivered by a marbled electric ray can be severe but is not directly life-threatening. Its electrogenic properties have been known since classical antiquity, when live rays were used to treat conditions such as chronic headaches. This and other electric ray species are used as model organisms in biomedical research. Various coastal demersal fisheries take the marbled electric ray as bycatch; captured rays are usually discarded as they have little commercial value. The impact of fishing on its population is uncertain, and thus International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed this ray under Data Deficient. In the Mediterranean Sea, it remains the most common electric ray and in some areas may be increasing in number.

Description

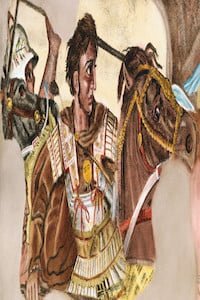

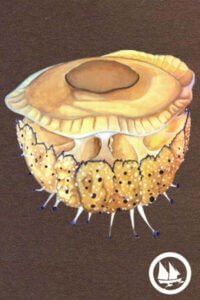

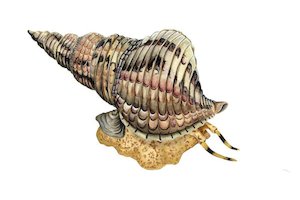

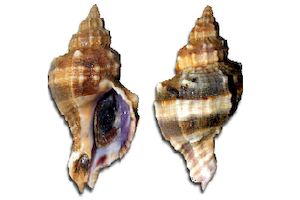

The marbled electric ray can be identified by its ornate color pattern and fringed spiracles.

This ray has the shape of a thick and rounded disc , which can reach 80 cm in diameter, 100 cm for the largest individuals. It has a developed caudal fin which provides propulsion by flapping and two dorsal fins, the first a little more developed than the second.

Its spiracles *, or vents *, just behind the eyes, are provided on their border with long papillae (six to eight) whose tips touch.

Its color is generally mottled to speckled with light or dark patterns on a beige to dark brown background , sometimes even more or less yellowish, greenish or blackish.

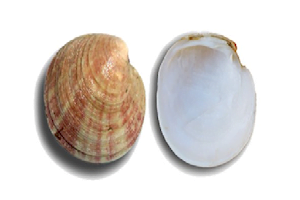

As in other rays, its gill slitsare visible on the stomach , behind the mouth.

The body of the marbled electric ray is soft and flabby, and entirely lacks dermal denticles. The thick pectoral fin disc is nearly circular and comprises about 59–67% of the total length; the paired kidney-shaped electric organs are visible beneath the skin, outside of the small eyes. Immediately posterior to each eye is a large, oval spiracle, which bears 6–8 long, finger-like projections on the rim that almost meet at the center. On the “nape” behind the spiracles, there are 5–7 prominent mucous pores. Between the nostrils, there is a quadrangular curtain of skin much broader than long, that almost reaches the small, arched mouth. The teeth are small with a single pointed cusp, and are arranged with a quincunx pattern into a pavement-like band in either jaw. The five pairs of gill slits are small and located beneath the disc.[5][11][12]

The two dorsal fins have rounded apexes and are placed close together; the base of each fin measures about two-thirds its height. The rear of the first dorsal fin base is located behind the rear of the pelvic fin bases. The second dorsal fin is only slightly smaller than the first.[5][11] The short, robust tail has skin folds running along either side, and terminates in a large caudal fin shaped like a triangle with blunt corners.[6][12] The upper surface has a dark mottled pattern on a light to dark brown background; some individuals are uniformly brown.[11] The underside is plain off-white with darker fin margins.[13] This species can grow up to 1 m (3.3 ft) long,[5] though few exceed 36–38 cm (14–15 in) long for males and 55–61 cm (22–24 in) long for females. The much larger sizes attained by females can be attributed to the resource investment needed for reproduction. There seems to be little geographic variation in maximum size.[14][15] The maximum weight on record is 3 kg (6.6 lb).[5]

Distribution and Habitat

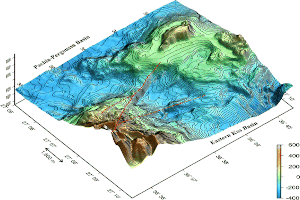

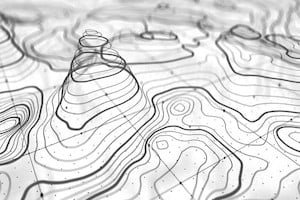

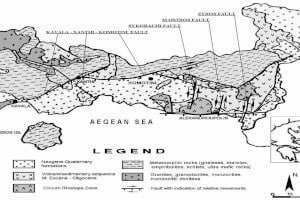

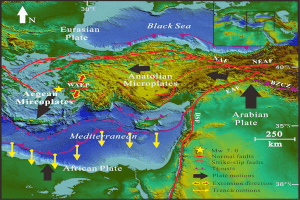

Widely distributed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, the marbled electric ray is found from Scotland and the southern North Sea southward to the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, including all around the Mediterranean Sea. It prefers temperatures cooler than 20 °C (68 °F).[1][6] This species is typically found at depths of 10–30 m (33–98 ft) off Britain and Ireland,[7] 20–100 m (66–328 ft) off Italy, and down to 200 m (660 ft) off Tunisia.[8] It has been recorded from as deep as 370 m (1,210 ft).[5] The marbled electric ray tends to be found deeper than the common torpedo (T. torpedo), which shares the southern portion of its range.[8]

Bottom-dwelling in nature, the marbled electric ray inhabits rocky reefs and seagrass beds, as well as nearby areas with sandy or muddy bottoms.[6] During warm summer months, pregnant females are known to migrate into Arcachon Bay in northwestern France, where they are commonly found in very shallow, muddy pools near oyster beds.[9][10] This species may conduct a northward migration in summer and autumn, into the waters of the British Isles.[7]

Biotope

It will be found between 10 and 100 m deep on average in the Mediterranean, most often on sandy-muddy coasts, seagrass beds, especially Posidonia , or near rocks.

In the Atlantic it is found from the shore to a depth of 50 m.

Taxonomy

French naturalist Antoine Risso described the marbled electric ray as Torpedo marmorata in his 1810 Ichtyologie de Nice, ou histoire naturelle des poissons du département des Alpes maritimes (Ichthyology of Nice, or natural history of fishes in the Alpes-Maritimes). The specific epithet marmorata means “marbled” in Latin, and refers to the ray’s color pattern.[2] Because no type specimens are known, in 1999 Ronald Fricke designated Risso’s original illustration as the species lectotype.[3]

Within the genus Torpedo, the marbled electric ray belongs to the subgenus Torpedo, which differs from the other subgenus Tetronarce in having fringed margins on their spiracles and generally ornate dorsal coloration.[4] Other common names for this species include common crampfish, marbled torpedo, numbfish, and spotted torpedo.[5]

Biology and Ecology

Solitary and slow-moving,[13] the marbled electric ray may remain motionless for several days at a time.[9] It is more active at night and spends much of the day buried in sediment with only the eyes and spiracles showing.[1] Consistent with its sluggish nature, the marbled electric ray has a low blood oxygen carrying capacity and heart rate (10–15 beats/min), and consumes less oxygen than other sharks and rays of similar size.[9] It is highly tolerant of being deprived of oxygen (hypoxia), allowing it to cope with deoxygenated bottom waters or being stranded in small pools by the falling tide. The ray stops breathing entirely when the oxygen partial pressure in the water drops below 10–15 Torr, and can survive such a state for at least five hours. It deals with extreme hypoxia by coupling anaerobic glycolysis to additional energy-producing pathways in its mitochondria, which serves to slow down the accumulation of potentially harmful lactate within its cells.[16]

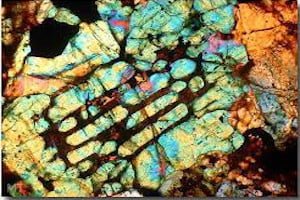

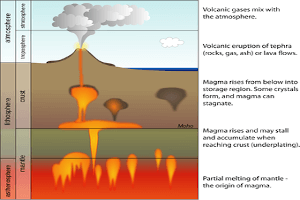

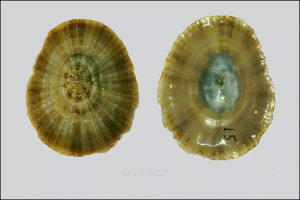

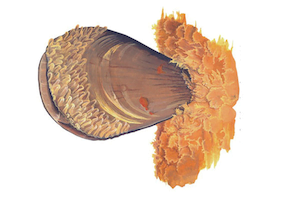

Like other members of its family, the marbled electric ray can produce a strong electric shock for attack and defense, produced by a pair of electric organs derived from muscle tissue. Each electric organ consists of 400–600 vertical columns, with each column composed of a stack of roughly 400 jelly-filled “electroplates” that essentially act like a battery.[10] This ray has been measured producing up to 70–80 volts, and the maximum potential of the electric discharge has been estimated to be as high as 200 volts. The strength of the electric shock declines progressively as the ray becomes fatigued.[12] Experiments in vitro have found that the nerves innervating the electric organ essentially stop functioning at temperatures below 15 °C (59 °F). As the water temperature in the wild regularly drops below this threshold in winter, it is possible that the ray does not use its electric organ for part of the year. Alternately, the ray may have a yet-unknown physiological mechanism to adapt electric organ function to the cold.[17]

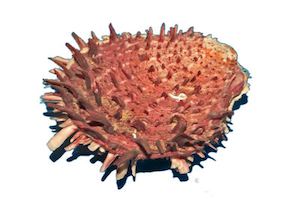

Known parasites of the marbled electric ray include the tapeworms Anthocephalum gracile[18] and Calyptrobothrium riggii,[19] the leeches Pontobdella muricata and Trachelobdella lubrica,[20] the monogeneans Amphibdella torpedinis,[21] Amphibdelloides kechemiraen,[22] A. maccallumi,[21] A. vallei,[22] Empruthotrema raiae, E. torpedinis,[23] and Squalonchocotyle torpedinis,[24] and the nematodes Ascaris torpedinis and Mawsonascaris pastinacae.[6]

Alimentation

The marbled electric ray is an ambush predator that employs electricity to capture prey. Vision is of little importance in hunting, as the ray’s eyes are often obscured as it lies buried on the bottom. Instead, it likely relies on the mechanoreceptors of its lateral line, as it only attacks moving prey. The electroreceptive ampullae of Lorenzini may also contribute to prey detection.[25]

A predatory species mainly of small benthic fish *, much more rarely of crustaceans (shrimps) and molluscs (cuttlefish). It approaches its prey and, once in proximity to it, it paralyzes it with an electric shock, before covering it to devour it. The torpedo swallows its prey without ceasing to perform electric shocks.

Sometimes this electric shock to paralyze the prey can be such that it has the ability to sever the spine of the passing fish when the fish contracts in shock.

Reproduction

The individuals are of separate sexes. This species is viviparous, with a reproductive cycle that spans 2 years.

The male has two copulation organs: the pterygopods *, which result from the modification of the pelvic fins. At the time of mating (we will luckily observe the two rays belly to belly), it will use only one to penetrate the cloaca of the female.

Fertilization is therefore internal, and after gestation of 8 to 10 months, the female torpedo ray will give birth to two to thirty juveniles at a time, these being able to reach 10 cm. The larger the female, the greater the number of young.

The calving period varies depending on the geographical position and extends from October to December for individuals living in the Mediterranean and from November to May in the Atlantic.

Small, benthic bony fishes constitute over 90% of the marbled electric ray’s diet by weight;[26] these include gobies, hake, sea bass, mullets, jack mackerel, sea breams, goatfish, damselfish, wrasses, conger eels, and flatfish.[5][8][11] Cephalopods such as European squid (Loligo vulgaris) and elegant cuttlefish (Sepia elegans) are a minor secondary food source. There is a single record of an individual that had swallowed a penaeid prawn, Penaeus kerathurus,[26] and a study of captive rays found that they reject live Macropodia crabs.[27] Off southern France, by far the most important prey species is the leaping mullet (Liza saliens).[26] Food items are swallowed whole; there is a record of a ray 41 cm (16 in) long that had consumed a three-bearded rockling (Gaidropsarus vulgaris) 34 cm (13 in) long.[11]

Two distinct types of prey capture behavior have been observed in the marbled electric ray. The first is “jumping”, used by the ray to attack prey fish that swim close to its head, typically no farther than 4 cm (1.6 in). In the “jump”, the ray pulls back its head and then thrusts its disc upwards, reaching about two or three times as high as the prey fish is from the bottom. Simultaneously, it makes a single tail stroke and produces a high-frequency (230–430 Hz, increasing with temperature) burst of electricity. The initial electric burst is very short, containing only 10–64 pulses, but is still strong enough to cause tetanic contraction in the body of the prey fish, often breaking its vertebral column. As the ray glides forward, the motion of the jump sweeps the now-paralyzed prey beneath it, whereupon it is enveloped by the disc and maneuvered to the mouth. Electric bursts continues to be produced during this process; the total number of electric pulses over a single jump increases with size, ranging from 66 in a newborn 12 cm (4.7 in) long to 340 in an adult 45 cm (18 in) long. The jump lasts no more than two seconds.[25][27]

The second type of prey capture behavior is “creeping”, used by the ray for stationary or slow-moving prey; this includes stunned prey that may have drifted out of reach from a jumping attack. In creeping, the ray makes small up and down motions of its disc coupled with small beats of its tail. The raising of the disc draws water beneath it and pulls the prey towards the ray, while the lowering of the disc and the tail beats move the ray towards the prey in small increments. When it reaches the prey, the ray opens its mouth to suck it in. Short electric bursts are produced as necessary, depending on the movement of the prey, and continue through ingestion.[27]

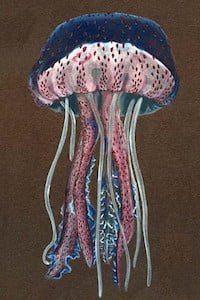

Similar Species

It can be confused with the black torpedo, Torpedo nobiliana (Bonaparte, 1835), but the latter has a marbling, black-purple coloration.

Confusions are also possible with the ocellated torpedo Torpedo torpedo (Linnaeus, 1758) but this species has 5 dark blue ocelli on the body and has no marbling.

Finally, the Alexandrian torpedo ( Torpedo alexandrinsis Mahzar, 1982) is a close species although the disc constituting the body is longer than it is wide and there are 7 short papillae around the vents.

Associated Life

Occasionally an annelid of the Hirudinea Subclass, the ray leech Branchellion torpedinis , parasite Torpedo marmorata to which it sucks blood.

Various Biology

This fish often remains motionless on the bottom, more or less well buried, and only letting its eyes appear to watch for its prey, which are mobile, mainly at night.

The electric shocks caused by this species last a fraction of a second. Their intensity is correlated with the size of the individual and they are delivered thanks to specific organs, in the shape of beans, located in the thickened areas, on either side of the head (see photo 10). These discharges can reach 45 V or more in this species (although other species of the genus can approach 230 V!).

Electric discharge is a voluntary act of the animal. It can generate several successive discharges but the intensity of the pulses decreases sharply when they follow one another. It will then take, like an electric battery, a certain time for the individual to recharge his electrical organs.

The generated electric field helps locate, attack and stun prey, but it also allows the fish to self-defense.

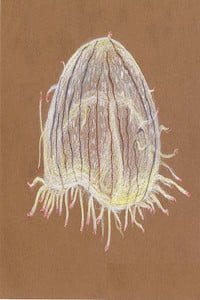

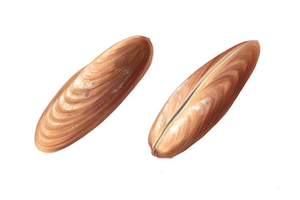

To produce its electricity, the ray therefore has specialized electrical organs. These are muscle structures made up in particular of cells called electrocytes. They are made up of columns of discs stacked from the skin of the back to that of the stomach and linked together by a gelatinous substance.

The brain supplies these discs with 5 electrical nerves. The disks are connected in series and each of them carries charges of opposite signs on its faces. Indeed, the ventral surface of these discs is negatively charged, the dorsal face is positively. The series connection of the disks makes it possible to generate a remarkable difference in electric potential for an intensity of 5 to 10 amperes and a frequency of up to 600 hertz. This is an electrochemical membrane potential of the same type that any animal cell can produce but it is, in the torpedo ray, amplified by the large concentration of ionic channels.

These rays perform seasonal migrations. This is how in the Arcachon basin one mainly meets gravid females who enter towards the end of May to leave at the beginning of October.

Defense

electric ray adopts

a defensive posture that facilitates

the delivery of electric shocks.

Because of its size and electrical defenses, the marbled electric ray does not often fall prey to other animals such as sharks.[6] This species exhibits different defensive behaviors depending on whether a prospective predator grasps it by the disc or the tail. A ray touched on the disc will quickly turn toward the threat while producing electric shocks; this is followed by it fleeing in a straight line, after which it may re-bury itself. A ray touched on the tail will propel itself upward into a loop; if it has not escaped after the maneuver, the ray will curl into a ring with the belly facing outward, so as to present the area of its body with the highest electric field gradient (the underside of the electric organs) towards the threat; these behaviors are accompanied by short, strong electric shocks. The ray tends to produce more electric bursts when protecting its tail than when protecting its disc.[27]

Life History

The marbled electric ray exhibits aplacental viviparity, in which the developing embryos are nourished initially by yolk, which is later supplemented by nutrient-rich histotroph (“uterine milk”) produced by the mother. Adult females have two functional ovaries and uteruses; the inner lining of the uterus bears a series of parallel lengthwise folds.[28] The reproductive cycle for females is probably biennial, while males are capable of mating every year. Mating occurs from November to January, and the young are born the following year after a gestation period of 9–12 months.[14][15] The litter size ranges from 3 to 32, increasing with the size of the female.[11][15]

The electric organs first appear when the embryo is 1.9–2.3 cm (0.75–0.91 in) long, at which time it has distinct eyes, pectoral and pelvic fins, and external gills. At an embryonic length of 2.0–2.7 mm (0.079–0.106 in), the gill clefts close dorsally, leaving the gill slits beneath the disc as in all rays. At the same time, the four blocks of primordial cells that make up each electric organ rapidly coalesce together. The embryo’s pectoral fins enlarge and fuse with the snout at a length of 2.8–3.7 cm (1.1–1.5 in), giving it the typical circular electric ray shape. When the embryo is 3.5–5.5 cm (1.4–2.2 in) long, the external gills are resorbed and pigmentation develops. The embryo can produce electric discharges by a length of 6.6–7.3 cm (2.6–2.9 in). The strength of the discharge increases by a magnitude of 105 over the course of gestation, reaching 47–55 volts by an embryonic length of 8.6–13 cm (3.4–5.1 in), close to that of an adult.[10]

Newborns measure approximately 10–14 cm (3.9–5.5 in) long,[1] and are immediately capable of performing characteristic predatory and defensive behaviors.[10] Males mature sexually at approximately 21–29 cm (8.3–11.4 in) long and five years of age, while females mature significantly larger and older at 31–39 cm (12–15 in) long and twelve years of age. The maximum lifespan is 12–13 years for males and around 20 years for females.[1]

Human Interactions

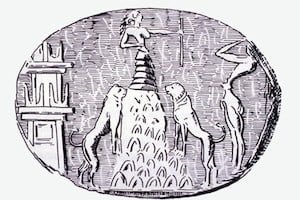

The shock delivered by the marbled electric ray can be painful but is seldom life-threatening, although there is a danger of a shocked diver becoming disoriented underwater.[6] Its electrogenic properties have been known since classical antiquity, leading it and other electric fishes to be used in medicine. The ancient Greeks and Romans applied live rays to those afflicted with conditions such as chronic headaches and gout, and recommended that its meat be eaten by epileptics.[13][29]

The marbled electric ray is caught incidentally in bottom trawls, trammel nets, and bottom longlines; it has little economic value and is mostly discarded at sea when captured. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) presently lacks enough population and fishery data to assess its conservation status beyond Data Deficient. At least in the northern Mediterranean, surveys have found that it remains the most common electric ray, and is perhaps becoming more abundant in Italian waters.[1] This and other electric ray species are used as model organisms in biomedical research because their electric organs are rich in acetylcholine receptors, which play an important role in the human nervous system.[30]

Further Information

Approaching this torpedo ray is fairly easy, but beware of electric shocks! They can be painful to humans, but are usually harmless. However, a large specimen can cause a shock liable to lead to a diving accident (shock, disaster recovery, etc.).

It has been observed in aquariums that if you touch a torpedo ray at rest, it turns against its attacker instead of fleeing as another fish could.

The electric shocks from the torpedo ray were once used as a therapeutic treatment to overcome epileptic shocks. The Romans also used this ability to treat rheumatism.

Today, the electrical capacities of Torpedo marmorata, and in particular the organs concerned rich in ion channels, make it a privileged subject of study for neurosciences.