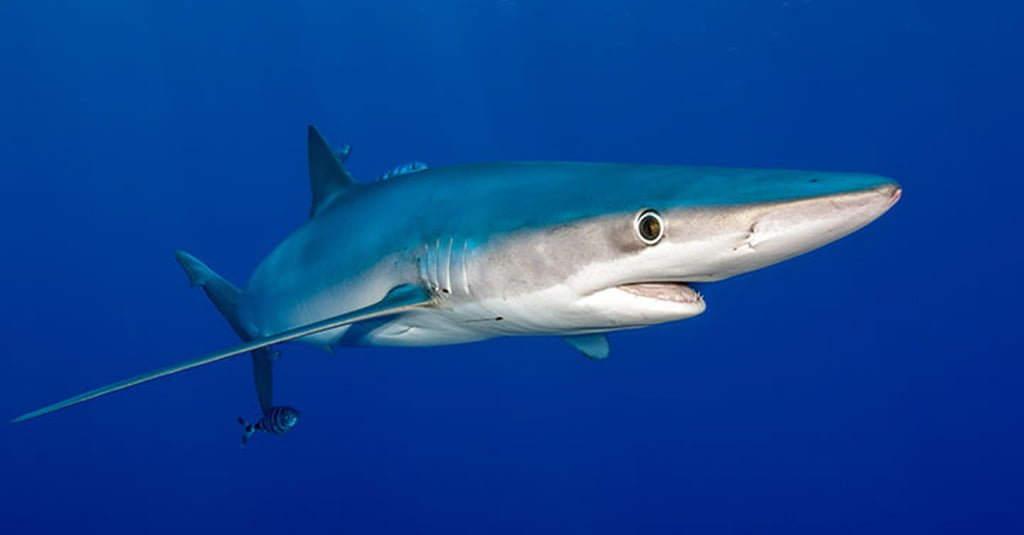

Prionace Glauca

– Blue Shark –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Near Threatened (IUCN 3.1)[2] |

| Scientific classification |

Prionace glauca (Linnaeus, 1758)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Prionace Cantor, 1849 |

| Species: | P. glauca |

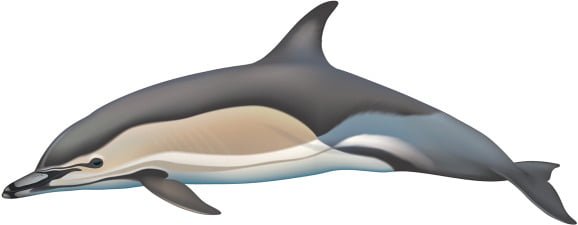

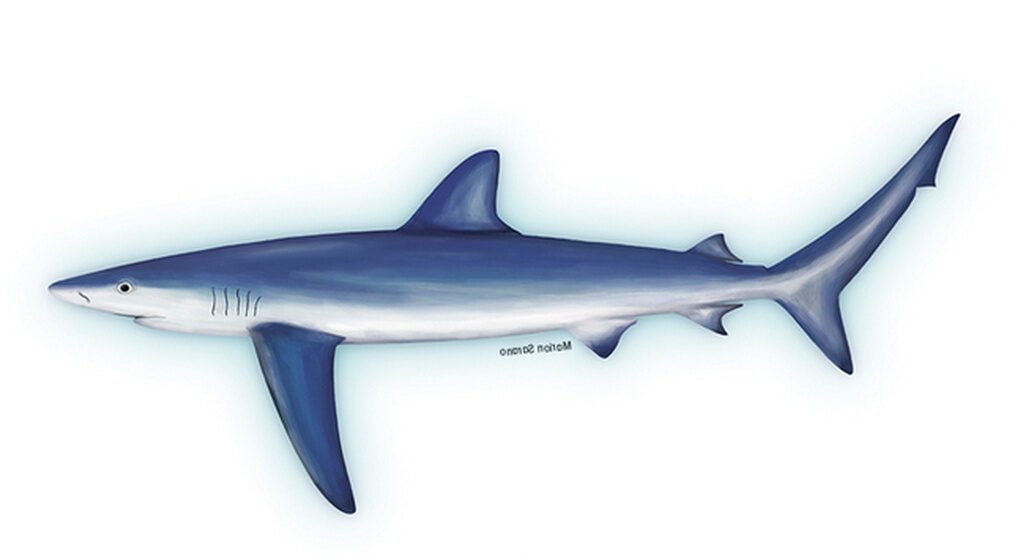

The blue shark (Prionace glauca) is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae, that inhabits deep waters in the world’s temperate and tropical oceans. Averaging around 3.1 m (10 ft) and preferring cooler waters,[3] the blue shark migrates long distances, such as from New England to South America. It is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

Although generally lethargic, they can move very quickly. Blue sharks are viviparous and are noted for large litters of 25 to over 100 pups. They feed primarily on small fish and squid, although they can take larger prey. Maximum lifespan is still unknown, but it is believed that they can live up to 20 years.[4]

Description

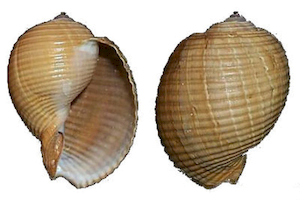

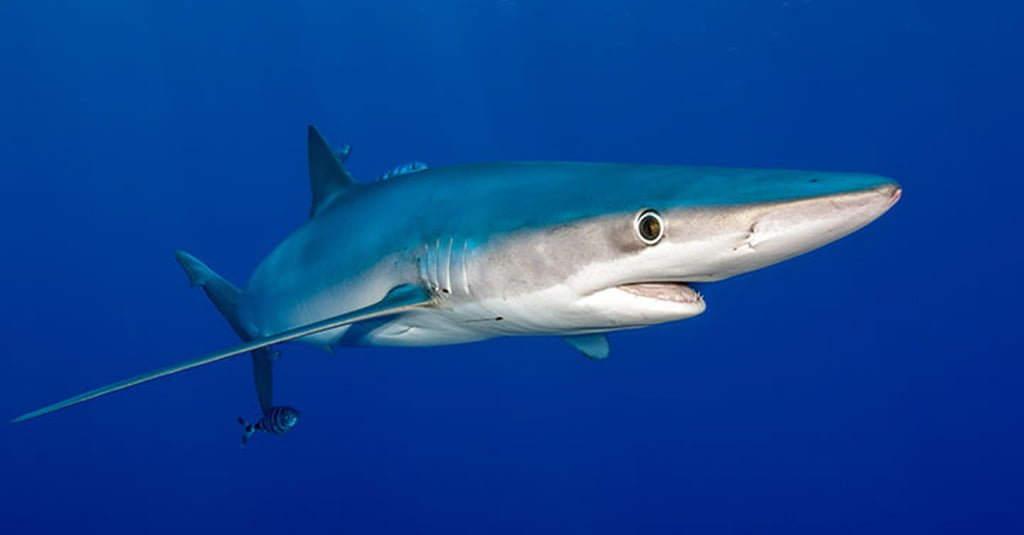

Blue sharks are light-bodied with long pectoral fins. Like many other sharks, blue sharks are countershaded: the top of the body is deep blue, lighter on the sides, and the underside is white. The male blue shark commonly grows to 1.82 to 2.82 m (6.0 to 9.3 ft) at maturity, whereas the larger females commonly grow to 2.2 to 3.3 m (7.2 to 10.8 ft) at maturity.[5] Large specimens can grow to 3.8 m (12 ft) long. Occasionally, an outsized blue shark is reported, with one widely printed claim of a length of 6.1 m (20 ft), but no shark even approaching this size has been scientifically documented.[5] The blue shark is fairly elongated and slender in build and typically weighs from 27 to 55 kg (60 to 121 lb) in males and from 93 to 182 kg (205 to 401 lb) in large females.[6][7][8] Occasionally, a female in excess of 3 m (9.8 ft) will weigh over 204 kg (450 lb). The heaviest reported weight for the species was 391 kg (862 lb).[9] The blue shark is also ectothermic and it has a unique sense of smell.

The tapered body of the blue shark is hydrodynamic. The color of its back varies from cobalt blue to electric blue , its sides and belly are white. It has a long muzzle with a parabolic mouth and large round eyes with a nictitating membrane *. Spiracles * are small or absent (small vents, remains of a branchial slit, located behind the eye).

The animal has five gill slits . The one in the center is the largest and the last two are located above its slender pectoral fins. The latter, sickle-shaped * and quite long , arecolored black at the ventral ends . The second dorsal is perfectly aligned with the anal fin; we note the presence of a little pronounced caudal carina. The caudal has a notch below the end of the upper lobe.

The maximum recorded height is 3.83 m . Some mention specimens over 5 m long, but caution should be exercised in the absence of scientific findings. The average is between 2.50 and 3 m .

The upper teeth are shaped like a large cusp * (crest), relatively narrow curved and oblique with serrated edges. The lower teeth, comparable, are even narrower and smooth at their base.

Dental formula *: 14 to 16 – 1 to 2 – 14 to 16/13 to 16 – 1 to 4 – 13 to 16 (i.e., here, a variable number of teeth per half-jaw and per half-mandible, including in central position).

Biotope

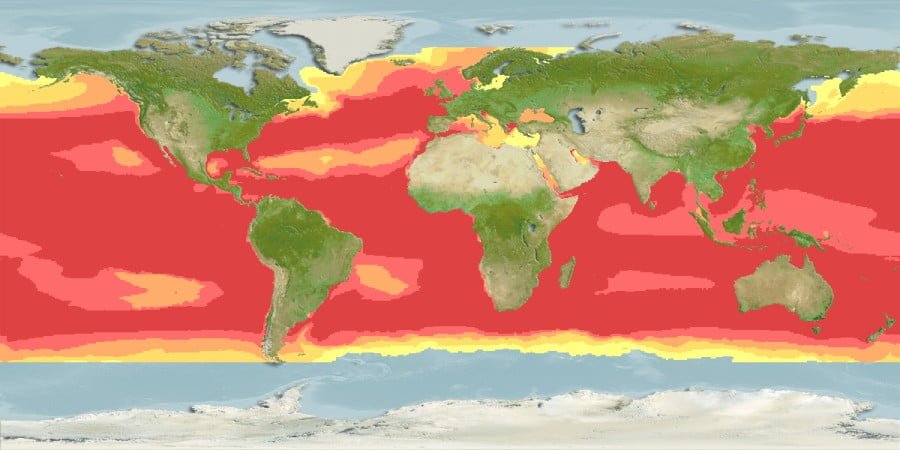

The blue shark is an oceanic and epipelagic shark found worldwide in deep temperate and tropical waters from the surface to about 350 m (1,150 ft).[10] In temperate seas it may approach shore, where it can be observed by divers; while in tropical waters, it inhabits greater depths. It lives as far north as Norway and as far south as Chile. Blue sharks are found off the coasts of every continent, except Antarctica. Its greatest Pacific concentrations occur between 20° and 50° North, but with strong seasonal fluctuations. In the tropics, it spreads evenly between 20° N and 20° S.[3] It prefers water temperatures between 12 and 20 °C (54–68 °F), but can be seen in water ranging from 7 to 25 °C (45–77 °F).[11] Records from the Atlantic show a regular clockwise migration within the prevailing currents.[3]

Ecology

Alimentation

Prionace glauca has a varied diet, consuming mainly small epipelagic species; it nevertheless makes nocturnal incursions into coastal areas to feed.

The blue shark particularly appreciates squid, of which it makes real orgies, going so far as to regurgitate to better feed itself when the resource is abundant. However, it also plays a role of scavenger, not disdaining the corpses of cetaceans, whose adipose layer constitutes a precious energy reserve.

Its menu also includes small sharks, octopus and crustaceans, even sea birds.

From Gibraltar, this shark joins the Ligurian-Provençal current in the Mediterranean, one of its well-identified pantries …

Squid are important prey for blue sharks, but their diet includes other invertebrates, such as cuttlefish and pelagic octopuses, as well as lobster, shrimp, crab, a large number of bony fishes, small sharks, mammalian carrion and occasional sea birds. Whale and porpoise blubber and meat have been retrieved from the stomachs of captured specimens and they are known to take cod from trawl nets.[3] Sharks have been observed and documented working together as a “pack” to herd prey into a concentrated group from which they can easily feed. Blue sharks may eat tuna, which have been observed taking advantage of the herding behaviour to opportunistically feed on escaping prey. The observed herding behaviour was undisturbed by different species of shark in the vicinity that normally would pursue the common prey.[12] The blue shark can swim at fast speeds, allowing it to catch up with prey easily. Its triangular teeth allow it to easily catch hold of slippery prey.

Reproduction

They are viviparous, with a yolk-sac placenta, delivering four to 135 pups per litter. The gestation period is between nine and 12 months. Females mature at five to six years of age and males at four to five. Courtship is believed to involve biting by the male, as mature specimens can be accurately sexed according to the presence or absence of bite scarring. Female blue sharks have adapted to the rigorous mating ritual by developing skin three times as thick as male skin.[3]

The maturity reached between 4 and 6 years corresponds to a size statistically close to 2.03 m for a male and from 1.86 m to 2.12 m for the female. In Prionace glauca , the latter’s skin thickens three times more than that of males, which protects it from copulatory bites suffered during reproduction. We also know that it supports colder water than its male counterparts. Thus, in the North Pacific, it has been noted that subadult females (measuring between 1.34 and 1.99 m) are kept north of the parturition areas, and that the subadult males are kept south of the same areas. As for the waters of the Channel, they are mainly frequented by females.

Mating occurs mainly from spring to early summer, after which females awaiting ovulation can store sperm for several months, perhaps even years.

The skin blue is viviparous placental *: fertilized eggs develop in the uterus from a yolk sac placenta serving. The embryo is first lecithotrophic * (it benefits from little or no exchange of nutrients directly from its parent). When resources are exhausted, the mother takes over and feeds each baby directly through the placenta attached to the wall of the uterine wall. An umbilical cord attaches each of them to this wall. This phenomenon is called matrotrophy * or maternotrophy *.

The blue-skinned female, like other shark species, has multiple uterine chambers. During gestation, the uteri compartmentalize into as many chambers as there are embryos. The development of the latter continues there until the end. Depending on her size, the female carries from four to one hundred and thirty-five embryos, ie, on average, twenty-five to fifty small 35 to 60 cm at birth.

Gestation lasts 9 to 12 months. Childbirth occurs between spring and autumn, during which the embryo breaks its ties. At birth, the juveniles are completely formed and totally independent.

The species has a long reproductive cycle, at least biennial (the organism must reconstitute itself before another fertilization), with a generation time of 8 years (8.1 to be precise, which corresponds to the interval between the birth and fertility of an individual).

We note that the Algerian coasts seem to correspond to a reproduction zone, while the Adriatic and the central Mediterranean constitute one of the nursery areas (also called nursery) of the species. The newborn finds there a favorable biological environment, allowing it to avoid (as much as possible) intraspecific (cannibalism) and interspecific competition.

The life expectancy is 16 to 20 years.

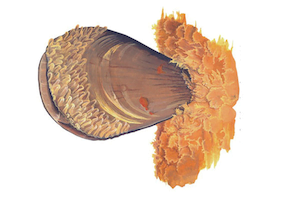

Associated Life

The blue shark is the target of three species of copepods ( Kroyeria lineata , Phyllothereus cornutus and Echthrogaleus coleoptratus ) and of several Cestodes but also of the nematode Anisakis simplex . The first two attach to the gills, the third to the skin. The last parasite was observed in the third larval stage, both in the stomach and the spiral valve constituting the intestine, but it could be an accumulation linked to the consumption of prey without the shark being directly concerned.

Predators

Young and smaller individuals may be eaten by larger sharks, such as the great white shark and the tiger shark. Killer whales have been reported to hunt blue sharks.[13] This shark may host several species of parasites. For example, the blue shark is the definitive host of the tetraphyllidean tapeworm, Pelichnibothrium speciosum (Prionacestus bipartitus). It becomes infected by eating intermediate hosts, probably opah (Lampris guttatus) and/or longnose lancetfish (Alepisaurus ferox).[14]

Various Biology

Sometimes solitary, sometimes gregarious * in its seasonal movements, Prionace glauca groups together in schools of individuals often of the same sex and of the same size (segregation *).

The populations of the northern and southern ocean basins have been shown to be genetically different; on the other hand it seems that the blue skins do not circulate from one ocean to another: there is no communication by the Arctic Ocean nor the Antarctic.

West Atlantic attendance peaks in late summer and fall. In Canadian waters, its presence on the Nova Scotia shelf occurs in late spring, while it begins during the summer in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in early fall for the Grand Bank.

No notorious blue-skinned predators are not known, but juveniles may fall prey to great white sharks ( Carcharodon carcharias ), shortfin mako sharks ( Isurus oxyrinchus ) as well as Otariids (such as Zalophus californianus ) which regulate populations.

If swimming is slow most of the time, the blue skin belongs to the category of the fastest sharks, with a top speed of around 69 km / h.

The intensification of pelagic fishing over the last thirty years has generated dramatic repercussions on the blue-skinned population in the Mediterranean. The nearly 40% decrease in catches must be correlated with a decrease in size for 96% of them. Concretely, this means that the great majority of catches have not reached maturity. Similar results were obtained in the Bay of Biscay, where all subjects were immature (Cavanagh & Gibson, 2007).

The growth of Prionace glauca appears to be faster in spring.

Relationship to Humans

It is estimated that 10 to 20 million of these sharks are killed each year as a result of fishing.[citation needed] The meat is edible, but not widely sought after; it is consumed fresh, dried, smoked and salted and diverted for fishmeal. There is a report of high concentration of heavy metals (mercury and lead) in the edible flesh.[16] The skin is used for leather, the fins for shark-fin soup and the liver for oil.[3] Blue sharks are occasionally sought as game fish for their beauty and speed.

Blue sharks rarely bite humans. From 1580 up until 2013, the blue shark was implicated in only 13 biting incidents, four of which ended fatally.[17]

In captivity

Blue sharks, like most pelagic sharks, tend to fare poorly in captivity. The first attempt of keeping blue sharks in captivity was at Sea World San Diego in 1968,[18] and since then a small number of other public aquariums in North America, Europe and Asia have attempted it.[19] Most of these were in captivity for about three months or less,[19] and some of them were released back to the wild afterwards.[18] The record time for blue sharks in captivity is 246 and 224 days for two individuals at Tokyo Sea Life Park,[18] 210 days for an individual at New Jersey Aquarium,[19] and 194 days for one at Lisbon Oceanarium.[18]

Blue sharks are relatively easy to feed in captivity, and the three primary issues appear to be transport, predation by larger sharks and trouble avoiding smooth surfaces in tanks.[18] Small blue sharks, up to 1 m (3.3 ft) long, are relatively easy to transport to aquariums, but it is much more complicated to transport larger individuals.[18] However, this typical small size when introduced to aquariums means that they are highly vulnerable to predation by other sharks that are often kept, such as bull, grey reef, sandbar and sand tiger sharks.[18][19] For example, several blue sharks kept at Sea World San Diego initially did fairly well, but were eaten when bull sharks were added to their exhibit.[19] Attempts of keeping blue sharks in tanks of various sizes, shapes and depths have shown that they have trouble avoiding walls, aquarium windows and other smooth surfaces, eventually leading to abrasions to the fins or snout, which may result in serious infections.[18][19] To keep blue sharks, it is therefore necessary with tanks that allow for relatively long, optimum swimming paths where potential contact with smooth surfaces is kept at a minimum. It has been suggested that prominent rockwork may be easier to avoid for blue sharks than smooth surfaces, as has been shown in captive tiger sharks.[18]

Conservation Status

In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the blue shark as “Not Threatened” with the qualifier “Secure Overseas” under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[20] The species is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.[2]

Further Information

Attacks on humans are reported (especially in Newfoundland) and it is reported that the blue shark would not hesitate to attack the boats. These testimonies, insufficiently documented, should be taken with caution.

We do know, however, that the blue skin is capable of turning around twenty minutes around a diver. During his solo swim across the Atlantic (Dec. 16, 1994 – Feb. 9, 1995), Guy Delage was approached by a shark of this species, swimming slowly near the surface. The animal “could only be detected as it was about to bite the swimmer’s right calf. This slow and” gentle “attack strategy is typical of the blue shark. Before the attack, dolphinfish, which usually surrounded the swimmer, the