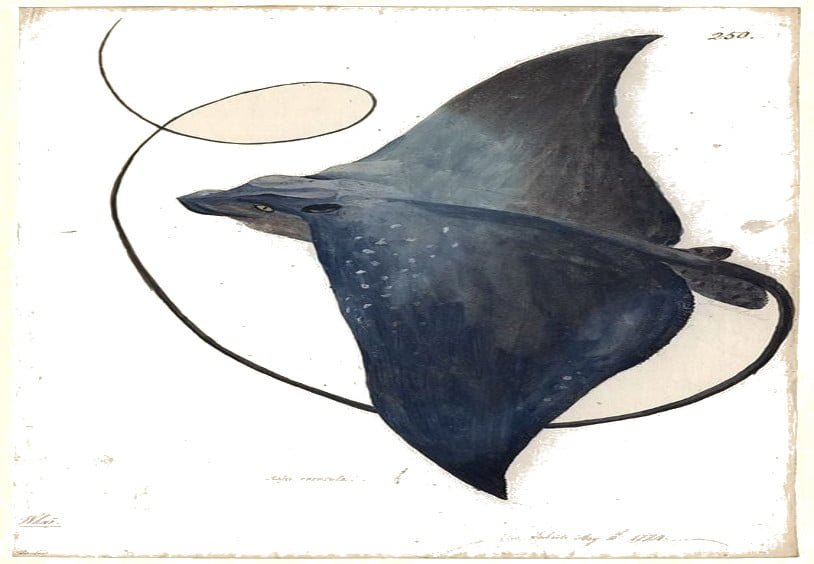

Mobula Mobular

– Devil Fish –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Endangered (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

| Scientific classification |

Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Family: | Mobulidae |

| Genus: | Mobula |

| Species: | M. mobular |

The devil fish or giant devil ray (Mobula mobular) is a species of ray in the family Mobulidae. It is currently listed as endangered, mostly due to bycatch mortality in unrelated fisheries.

Description

The devil fish is larger than its close relative the lesser devil ray. It grows to a maximum recorded length of 5.2 metres (17 ft), making it one of the largest rays. It possesses a spiny tail.[2] The devil fish is the largest species in the genus Mobula. It is the only mobulid species that lives in the Mediterranean Sea. The species has been observed to have a maximum disk width of 5.2 meters (roughly 17 feet).[3] The species is also considered endangered given its decreasing population density.[4]

[smartslider3 slider=267]

Mobula mobular is a ray that can reach 3.50 m in wingspan . The dimensions of 5.20 can be found in the literature but it is undoubtedly a question of errors of identification with another species of Mobula .

Its back is dark brown to bluish black , often with a large darker mark on the nape . The ventral side is white .

The devil of the sea has 2 large triangular pectoral fins , the animal therefore forming a large rhombus, twice as wide as it is long. The fins have an almost straight anterior edge, a very sharp lateral angle, and their posterior edge is markedly concave.

Mobula mobular has a broad head with the anterior part distinct from the rest of the body.

On the sides of the head, we can easily see the two cephalic fins, very flexible, which identify the “mantises”. Their outer face is whitish. In Mobula species , the ventral edges of the cephalic fins never overlap their dorsal margins when the animal curves them upward.

The eyes with the vertical pupil are in a lateral position, as are the spiracles *.

The mouth is located on the ventral side of the head.

We note the presence of a small dorsal fin (its base exceeding the level of the posterior tip of the pectoral fins).

The tail is long, since in good condition it greatly exceeds the wingspan of the animal. This whip-shaped tail, located just behind the dorsal fin, is armed with barbed spines at its base. On each side of this tail, there is a longitudinal row of white tubercles.

The dorsal surface of the pectorals bears sparse spinules * (small spines). On the midline and base of the tail, these spinules develop into large tubercles.

Like all elasmobranchs (rays, sharks, etc.), the gill slits are visible; these, 5 in number, are on the ventral part, on each side of the head. This ventral surface bears numerous spinules.

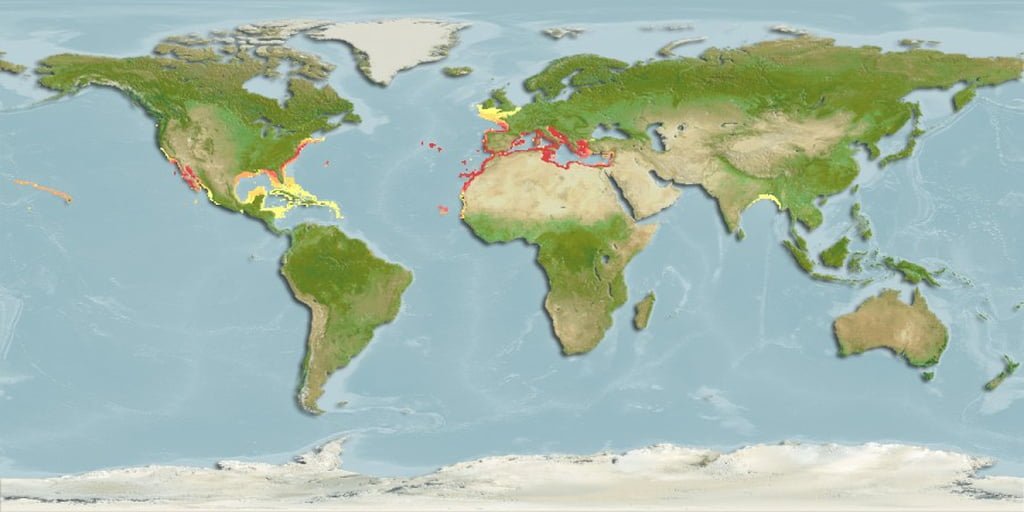

Distribution and Habitat

Devil fish are most common in the Mediterranean Sea and can be found elsewhere in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean, off the southwest coast of Ireland and south of Portugal, and possibly in the northwest Atlantic.[2] The species has been recorded in a number of Mediterranean countries such as Croatia, Greece, Italy, and Turkey, which shows that the species has a basin-wide distribution.[4] They predominantly prefer deep waters.[2]

Devil fish inhabit offshore areas to the neritic zone, their range as deep as several thousand meters. They are typically observed in small clusters, and may occasionally form larger groups.[1]

Giant devil rays are usually seen in deep coastal waters but are occasionally seen in shallow waters. In a tagging experiment conducted by the Italian National Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA), three giant devil rays were tagged and their depth was observed throughout different times of the day. The rays reached a maximum depth of 600-700 meters (1960-2300 feet) but mostly spent their time between 0 and 50 meters (0 and 165 feet); they prefer warmer waters with a temperature between 20°C and 29°C (68°F and 84°F). The giant devil rays also deep dive at random times, instances not correlated to the time of day unlike how other species deep dive at specific times of day.[3] In other observations studying ray abundance and habitat, giant devil rays were observed alone and occasionally in groups with a maximum of 18 rays. The same study also emphasizes that the rays undergo a species migration across the Mediterranean Sea with the seasons, taking advantage of warm, highly productive waters.[5]

Biotope

The devil of the sea lives from the surface up to 20-30 m depth (although it can descend much lower!). It is a species which frequents mainly the superficial oceanic waters, above the continental shelf (epipelagic zone).

Ecology

The average lifespan of a giant devil ray is 20 years. It is an epipelagic species. It has a very low reproductive capacity. This means that the species gives birth to a single offspring at unknown intervals.[6] The species is ovoviviparous: the young hatch from their eggs inside the mother’s body and emerge later when they are more fully grown.[1] It can be predicted that at the rate that its population is declining now, the population will decline by at least 50% in the next 60 years. This is due to a number of threats including the poor likelihood of recovering from declining populations.[6]

Alimentation

Devil rays feed on planktonic crustaceans and small schooling fish, which are trapped using the modified gill covers (branchial plates) responsible for its “devil-like” silhouette.[1] It mostly eats euphausiid shrimp (Meganyctiphanes norvegica) and small mesopelagic and clupeid fishes.[3]

If we think that the diet of each species of Mobula is specific, we can estimate for what we know that Mobula mobular feeds on zooplankton * fauna, in particular small crustaceans (shrimp larvae, copepods, etc. ) and probably small fish.

Sea devils feed while swimming. They unroll their cephalic horns (these can be unrolled and rolled up at will and independently of each other) which act as a funnel by directing a maximum of water, and therefore plankton, towards the open mouth. Zooplankton is picked up by the gills *. Indeed, the gills have a double function in rays: if they allow them to oxygenate their blood like most fish, they also filter the water to recover the plankton ingested. Despite the presence of small teeth on the jaws (ancestral remains), animals of the genus Mobula are filter feeders.

Reproduction

In sea devils, it is often difficult to spontaneously identify males from females. The only effective way is to distinguish the presence or not of the two pterygopods *, under the base of the tail. It is estimated that sexual maturity is reached from a wingspan of 2 m.

Reproduction is gonochoric * and sexual, fertilization is internal. It is an ovoviviparous * (aplacental viviparous) species. The baby therefore first feeds on the vitelline reserve and then feeds itself by indirect absorption of the enriched uterine fluid, before leaving already well formed. Mobula mobular gives birth to a single large-sized newborn (estimated wingspan of around 1.60 m for 35 kg). The interval between two parturitions is unknown.

Full term embryos have been observed during captures on the French, Sicilian and Tunisian coasts suggesting that births occur in the summer in the northern zone of the Mediterranean basin.

Similar Species

Mobula mobular is the only ray of the genus (there are nine species in the genus Mobula ) to frequent the Mediterranean.

But among the other species, some cross the extended distribution area of Mobula mobular if one avoids the problems of confusion with M. japanica .

Let us quote:

Mobula japanica (Müller and Henle, 1841): it is a species of the hot and temperate tropical waters of Africa but which perhaps frequents Europe. With a maximum wingspan of 3 m, M. japanica is a species extremely close to M. mobular(with very few dissimilar morphological characters, they are difficult to discriminate, maybe even identical, which generates controversies in the respective distributions of the two species; a fortiori in underwater observations). However, we can sometimes see a white spot at the tip of the dorsal fin, possibly a clear area behind the head. The back is dark blue to black, the white belly is sometimes speckled with gray.

Recent molecular studies () from 2015) suggest that M. japanica is only a junior synonym of M. mobular .

Mobula tarapacana(Philippi, 1893): this devil of the sea is widespread in all tropical to warm temperate seas and in particular on the African Atlantic coasts and its offshore archipelagos (Azores, Madeira …) where it could overlap with the distribution of M. mobular . With a wingspan of between 2.50 m and 3.50 m, Mobula tarapacana has two straight, thick and rather pointed horns. Its body is 1.6 times as wide as it is long and its ventral surface is white anteriorly, gray posteriorly with an irregular but sharp demarcation and dark markings at the gill slits. The back is brown to olive, the tail significantly shorter than the body.

There are still other species of the genus Mobulabut they are generally confined to the Atlantic tropics and / or Indo-Pacific, such as

Mobula birostris (Walbaum, 1792): it is the famous manta ray! It is found in most of the world’s tropical seas (circumtropical species) but it is on the African Atlantic coast and its offshore archipelagos (Canaries, Madeira) that it undoubtedly shares its distribution area with Mobula mobular (even s (it is probable to think today that the first identifications of M. mobular concerned in fact individuals of M. birostris lost in the Mediterranean).

The general shape resembles that of M. mobular. But with a wingspan of up to 8 m, it is the largest of the pelagic rays and the size alone makes it possible to distinguish it. The head is even larger than with Mobula mobular . It has two flattened, rounded, often curved cephalic horns, which can roll up on themselves (which M. mobular cannot do ), a very large terminal mouth (unlike M. mobular whose mouth is inferior) and a short tail without a poisonous sting. Blackish back (often with light markings) and white belly (with dark markings).

or

Mobula alfredi (Krefft, 1868): The reef manta has shoulder patches that curve towards the middle of the back and can meet. They form at the level of the spiracles a hook-shaped design that winds around the middle of the back. The ventral surface may have black spots in the middle area between the gill slits. She does not have a tail spine, nor a calcified mass on the posterior part of her back. The mouth is white or light gray in color. It is mainly found in the tropics and subtropics, in the Red Sea and in the tropical and subtropical West and central Indo-Pacific.

Regarding the other kinds of rays encountered in diving, let us note for a quick discrimination that the sea eagles (Myliobatidae), diamonds, have a prominent muzzle with a recognizable nose; mourines (Rhinopetridés) have a scalloped snout. As for the torpedo rays (Torpedinidae), stingrays (Dasyatidae) and related (Rajidae), they often have rather round pectoral fins and a shape to match and / or they live near the substrate.

Associated Life

The opportunities to inspect specimens of Mobula mobular are quite rare but on a female stranded near Narbonne (Gulf of Lion) in December 1966, two copepod parasites were found. One is Diphyllogaster thompsoni Brian, 1899 and Mobula mobular is the sole host of this species; the parasite was attached to the dorsal face of one of the wings. The other copepod, Eudactylina olivieri sp. was on the gill rays of the stingray.

We can also guess that a pelagic animal of this size will be followed by a few species of fish, using it as protection or the like. We have thus observed a regular of the fact: the pilot fish Naucrates ductorin the wake of Mobula mobular .

Various Biology

The outer surface of the cephalic lobes shows a predominantly whitish color in all Mobula species . The extreme flexibility of these appendages allowing to play with the appearance or disappearance of the clear zone induces the researchers to suggest that these white faces could play a role in social communication or in the gathering of food.

Along the entire length of the jaws, there are 150 to 160 parallel and spaced rows of small, short, sharp, overlapping teeth.

The branchial apparatus has horny membranous plates with free edges.

A study ([Canese & al. 2011]) reports that three adult specimens tagged in the Strait of Messina (passage between the boot of Italy and Sicily) spent more time in the first 50 meters of the column of water, preferably remaining above the thermocline with a temperature between 20 and 29 ° C; they went deep in the morning, between 6 a.m. and 12 p.m. Unlike the basking shark ( Cetorhinus maximus ), the devil does not perform a vertical migration responding to that of zooplankton. It remains mostly in the upper layers; its deep immersions are not correlated with the hours of the day. This preferential behavior for warm surface water could facilitate the maintenance of body heat.

Conservation Status

The devil fish has a limited range and a low rate of reproduction. As a result, it is sensitive to environmental changes.[7][5] Its population trend is decreasing. Most of the information on the giant devil ray has been gathered through bycatch data because the species has a high bycatch mortality. Giant devil ray mortalities are mostly reported as bycatch from swordfish nets, and occasionally reported as bycatch from longlines, purse seines, trawls, trammel nets, and tuna traps.[3] There are many threats against the giant devil ray such as fishing, resource harvesting (being taken as bycatch in different fisheries), industrial garbage, and solid waste.[6] The main threats to this species come from pollution in the Mediterranean and bycatch capture in various fishing equipment including trawls, tuna traps, and dragnets meant for swordfish.[5][7] All species of the genus Mobula have been targeted by recreational and commercial fisheries for centuries.[8] Fisheries in Gaza and Egypt are reported to catch giant devil rays for local consumption, and they are reported as bycatch in various places including the Indian Ocean and Atlantic Ocean.[8]

The 2004 IUCN Red List listed the devil fish as a vulnerable species. It was reclassified as endangered in 2006 due to low population resilience coupled with continued high bycatch mortality.[1] In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the devil fish as “Data Deficient” with the qualifier “Secure Overseas” under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[9] Off of the Adriatic Sea, the giant devil ray is legally protected in Italy and Croatia. Fishing, transportation, landing, and trade of the giant devil ray is forbidden in Albania. The giant devil ray is also protected under the Bern and Barcelona conventions.[4]

Further Information

The adult Devil Seals are usually encountered solitary or in pairs, although occasionally groups of 2 to 6 pre-adults can be seen near the coast or offshore.

Seen from the surface, it is sometimes a pectoral fin slicing through the water, like a fin, which can make it possible to spot a devil of the sea.

The animal can occasionally be seen jumping out of the water!

Mobula mobularhas a low reproduction rate with limited litters. Therefore, it is extremely vulnerable and sensitive to environmental changes. The main threats to this species therefore come from pollution in the Mediterranean. It is also the object, accidental certainly, of the involuntary capture by various fishing equipment (trawls, traps, dredges intended for swordfish, etc.). It has hardly any predator locally, except humans.

It rarely appears on fishmongers’ stalls (a little more occasionally in Sicily).

Two associations carry out joint monitoring of this ray in the Mediterranean: AILERONS and Corsica – Research Group on Mediterranean Sharks(forms to be filled in on the context of the observation and photo collections).

Understanding the correct taxonomy of manta and devil rays ( Mobula spp.) Has remained difficult since the initial description of the first two species of the monotypic Mobulidae family at the end of the 18th century (Bonnaterre, 1788; Walbaum, 1792). Confusion has persisted in nomenclature for centuries, exacerbated by erroneous reports and identifications of mobulid species across the world’s oceans. It is very likely that the descriptions and studies evoking the large sizes of these animals, blithely exceeding 5 m, were in fact carried out on Mobula birostris , lost in the Mediterranean where they had never been reported until then.