Carcharinus Plumbeus

– Sandbar Shark –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Vulnerable (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

| Scientific classification |

Carcharhinus plumbeus (Nardo, 1827)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. plumbeus |

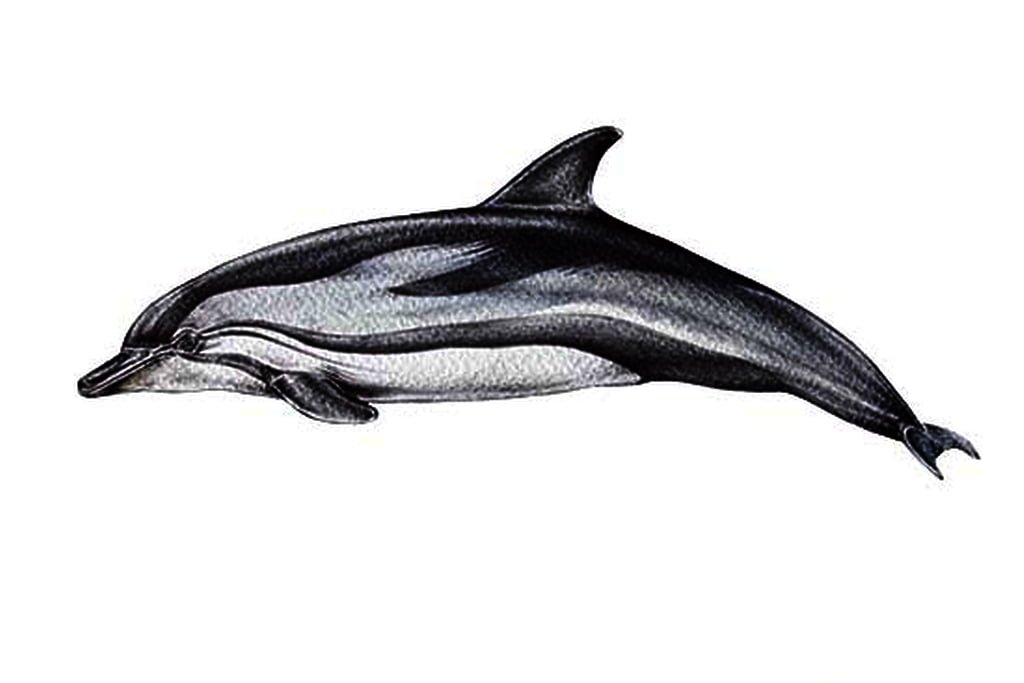

The sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus) is a species of requiem shark, and part of the family Carcharhinidae, native to the Atlantic Ocean and the Indo-Pacific. It is distinguishable by its very high first dorsal fin and interdorsal ridge.[2] It is not to be confused with the similarly named sand tiger shark, or Carcharias taurus.

Description

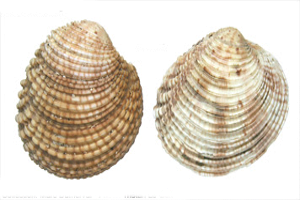

The sandbar shark is also called the thickskin shark or brown shark. It is one of the biggest coastal sharks in the world, and is closely related to the dusky shark, the bignose shark, and the bull shark. Its dorsal fin is triangular and very high, and it has very long pectoral fins. Sandbar sharks usually have heavy-set bodies and rounded snouts that are shorter than the average shark’s snout.

Its upper teeth have broadly uneven cusps with sharp edges. Its second dorsal fin and anal fin are close to the same height. Females reach sexual maturity around the age of 13 with an average fork-length (tip of the nose to fork in the tail) of 154.9 cm, while males tend to reach maturity around age 12 with an average fork-length of 151.6 cm.[3] Females can grow to 2–2.5 m (6.6–8.2 ft), males up to 1.8 m (5.9 ft). Its body color can vary from a bluish to a brownish grey to a bronze, with a white or pale underside. Sandbar sharks swim alone or gather in sex-segregated schools that vary in size.

Carcharhinus plumbeus is a shark relatively easy to identify by its silhouette. It has a massive, stocky body with a back provided with a high keel (hunchbacked part) carrying a very high dorsal fin .

The back, sides, fins are uniformly gray (sometimes more or less bronze). Only the ventral part is whitish. The size very rarely exceeds 2 m , animals of 2.50 m having nevertheless been encountered.

At the front, the head is quite flattened, the muzzle short, broad and rounded.. The eyes are small and round, with a fully functional lower nictitating * membrane (a sort of third eyelid, covering the eye to protect it). Under the muzzle and in line with the eyes, a curved mouth opens. It often remains ajar.

Like all carcharhiniformes, the gray shark has five independent gill slits on either side of the head.

On the anterior part of the body and originating from the fourth gill slit, the pectoral fins , half sickle-shaped * (leading edge a little more rounded than the rear edge), are imposing, long and rather pointed .

On the hunchbacked part of the back ,the first dorsal fin, triangular in shape, has its origin clearly in line with the axis of the pectoral . This dorsal fin is very high , making it easier to identify the species. Behind, the second dorsal fin is much more discreet. Between the two, an interdorsal wrinkle (small ridge of skin) is not very marked.

On the lower part of the animal, the pelvic fins precede the anal fins (which are relatively close to the former). The anals are directly above the second dorsal. In males, the pelvic membranes are modified and show two pterygopods *.

The shark’s body ends in a heterocercal * caudal fin (asymmetrical) whose upper part is more developed. At the end of the upper lobe, we can notice an apical triangle.

The fins of C. plumbeus are gray and do not show an obvious colored part, although the tip and posterior edge may be a little darker than the rest.

Distribution and Habitat

Biotope

Both coastal and bentho-pelagic *, Carcharhinus plumbeus lives above continental and island shelves. Often near estuaries, it frequently evolves in sandy, silty bottoms and frequents muddy port areas as well as lagoons and bays. Even if its area of evolution is mainly between 20 and 80 m, it can cross between the surface and 1800 m.

The sandbar shark, true to its nickname, is commonly found over muddy or sandy bottoms in shallow coastal waters such as bays, estuaries, harbors, or the mouths of rivers, but it also swims in deeper waters (200 m or more) as well as intertidal zones. Sandbar sharks are found in tropical to temperate waters worldwide; in the western Atlantic they range from Massachusetts to Brazil. Juveniles are common to abundant in the lower Chesapeake Bay, and nursery grounds are found from Delaware Bay to South Carolina. Other nursery grounds include Boncuk Bay in Marmaris, Muğla/Turkey[4] and the Florida Keys.[3]

Alimentation

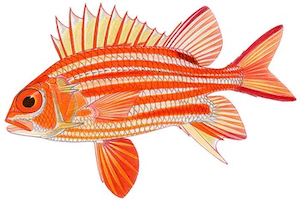

Active mainly at night, its diet is mainly composed of fish (Osteichthyans and Chondrichthyens) as well as cephalopods and crustaceans, which are nevertheless only secondary prey.

This predator observes a hunting procedure which is personal to him, with an attack which is performed obliquely. The sharp teeth of the lower jaw planted in his victim, he advances his upper jaw to drive in sharper teeth then begins a violent swing allowing the two jaws to meet and thus tear pieces of good size.

Reproduction

Carcharhinus plumbeus is a placental viviparous * species. The maturity of males is reached when their size is around 1.30 m to 1.80 m while for females, it is necessary to wait for a size of 1.45 to 1.80 m.

During the mating period, the individuals are found on the breeding sites. Mature, sexually available females release a chemical message into the water that educates males. A pursuit of the males behind the females is set up only on the traceability of an olfactory message, the male follows the female by the scent she gives off and tries to mate with her. No female, already pregnant or not mature, or who has not delivered an olfactory message, will be attacked by breeding males.

A period of fasting takes place during this phase which lasts about a week in females.

The actual mating process begins when the male follows a female, biting her between the dorsal fins to slow down her swimming and thus try to grab one of her pectoral fins by its jaw.

Once “stowed” in this way, one of his partner’s pectorals entirely in the mouth, the male finds himself next to the female. It is at this moment that he tries to insert one of his two pterygopods * (copulatory appendages), the right if it is on the right side, the left if it is on this side, in the cloaca * of the female. The sperm will thus be transmitted (internal fertilization).

It is therefore a violent and traumatic coupling for the females, the bites inflicted by the males leaving many traces in their partner, despite the greater thickness of the skin in the latter. Indeed, as in other species of sharks, females of C. plumbeus are often seen with scars on the sides and on the back due to this mating ritual.

Gestation generally lasts between 8 and 12 months, depending on the temperature and the place of life. The range varies between 1 and 16 cubs (maximum). They will reach at birth a size of between 56 and 75 cm and, when they come out, these little ones will be endowed with developed motor and sensory systems already allowing real autonomy.

It can be noted that the female has the ability to postpone the fertilization of mature oocytes * up to two years after insemination. Indeed, it can store, at the level of the nidamentary glands (part of the oviduct *), the precious semen of the male (s) for later use. It has also been observed that a single copulation can give rise to several pregnancies.

The embryos are supported in placental yolk sac inside the mother. Females have been found to exhibit both biennial and triennial reproductive cycles, ovulate in early summer, and give birth to an average of eight pups, which they carry for 1 year before giving birth.[3] The longevity of the sandbar shark is typically 35–41 years.[5]

Similar Species

Carcharhinus plumbeus is a relatively easy to recognize species. Indeed, its very high triangular dorsal fin and its positioning avoid confusing it. The other sharks-requiems (Carcharhinidae) which can possibly lead to confusion have this smaller first ridge and most often placed further back ( Carcharhinus limbatus , C. obscurus , C. leucas , …). Some have distinctive white or black markings on their fins ( C. albimarginatus , C. amblyrhynchos , C. melanopterus , etc.), some have a more or less homocerque caudal * ( Lamna nasus , Carcharodon carcharias ,…). More often than not, it is even a combination of these characters that makes it possible to differentiate shark-requiem species.

One of the problems to be noted, however, concerns the vernacular name and leads to species confusion. Indeed, there is a second shark commonly called “gray shark”, it is Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos . This is why it is preferable to specify for C. amblyrhynchos, “gray reef shark”.

Associated Life

In the Northwest Atlantic, it was found on male and female specimens, the presence of parasitic copepods, Alebion lobatus . Taking advantage of the absence of one or more placoid scales *, forming a crevice, the copepod parasitizes the external surface of its host.

Carcharhinus plumbeus is a prized species for breeding and breeding in captivity. As a result, studies and observations are numerous for this species. Strains of the bacterium Vibrio harveyi (not specialized in sharks) were thus taken from the gray shark (as well as the lemon shark Negaprion acutidens). The infection by bacteria led to various symptoms (lethargy, anorexia, loss of sense of direction, infections …) until the death of the animal which carried necrosis, subcutaneous cysts and lesions. external and internal tissue at all levels! [Bertone & al. 1996]

Predators

Natural predators of the sandbar shark include the tiger shark, and rarely great white sharks.

Various Biology

The half-open mouth reveals a dentition made up of 14 to 15 rows of teeth. The upper teeth are wide, triangular and denticulate in shape, with a high cusp *. The lower teeth are narrower and more finely serrated. The front teeth are erect and symmetrical, but the farther away from the center of the jaw, the more the teeth become oblique and smaller.

The teeth of Carcharhinus plumbeus , as in many Carcharhinidae, have the particularity of renewing themselves indefinitely. The phenomenon is due to the constant development of the gum tissue, which, covering the edge of the jaw, creates tension, thereby straightening new perfectly sharp teeth.

The gray shark is constantly in motion because it does not have gill muscles and therefore has to swim constantly in order to allow water to circulate in its mouth. This thus prevents it from being suffocated by the supply of oxygen present in the medium.

On average, females weigh 68 kg compared to 50 kg for males. However, specimens weighing up to 118 kg are described in various publications.

The lifespan of this species is estimated to be around 30 years or even a little longer.

The gray shark generally lives in groups during the day but prefers to remain solitary at night, during the hunt.

Interactions with Humans

Fishing restrictions

Sandbar sharks have been disproportionately targeted by the U.S. commercial shark fisheries in recent decades due to their high fin-to-body weight ratio, and U.S. fishing regulation requiring carcasses to be landed along with shark fins. In 2008, the National Marine Fisheries Service banned all commercial landings of sandbar sharks based on a 2006 stock assessment by SEDAR, and sandbar sharks were listed as vulnerable, due to overfishing. Currently, a small number of specially permitted vessels fish for sandbar sharks for the purpose of scientific research. All vessels in the research fishery are required to carry an independent researcher while targeting sandbars.[3]

Danger to people

In spite of their large size and similar appearance to other dangerous sharks such as bull sharks, very few, if any attacks are attributed to sandbar sharks, so they are considered not to be dangerous to people. As a result, they are considered one of the safest sharks to swim with and are popular sharks for aquaria.

Further Information

The gray shark is part of the “sharks-requiems” (nickname given to the family Carcharhinidae).

Sharks-requiems generally show on their dress a particular graphic “pattern” (the “requiem pattern” [Louisy 2002]) consisting of two stripes, white and gray staggered on their sides. This “requiem pattern” is, in C. plumbeus , little marked, almost invisible compared to other species.

Numerous specimens of gray sharks congregate in schools of different sizes and sexes before making large seasonal migrations. The water temperature has a lot to do with it, but the great ocean currents are thought to play an important role as well. These migrations show quite different characteristics (periods, composition of groups, distances, etc.) depending on the location of the populations of gray sharks.

Carcharhinus plumbeus is not known to be particularly dangerous to humans. However, he displays a daring curiosity towards an element new in his perimeter such as a diver, a boat and does not hesitate to approach them very close. Once his curiosity is satisfied, he moves away instantly.

The word “shark” probably comes, the hypothesis is not certain, from the word “requiem” (death, eternal rest). The latter, if the use has been lost, was also used to designate the animal shark, as evidenced by old French dictionaries of the seventeenth century. Some of them offer two reasons for choosing the word requiem. On the one hand, “the French called it that because there is nothing more than to blackmail requiem (the mass of the dead) for those who are bitten by it” or “others want us to gave this name (rest) because it is used to appearing when the weather is quiet “( ” Dictionary of Arts and Sciences “, 1694).

A little later, the word “shark”

(the shark) has received the sinister name it bears, and which, awakening so many gloomy ideas, above all recalls death, of which he is the minister. Shark is indeed a corruption of requiem, which for a long time designates, in Europe, death and eternal rest, and which must have often been, for frightened passengers, the expression of their dismay, at the sight of a shark more than thirty feet in length, and victims torn or swallowed up by this tyrant of the waves . “

Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon,” Histoire naturelle, générale et particularly des poisson “, XIXth century.