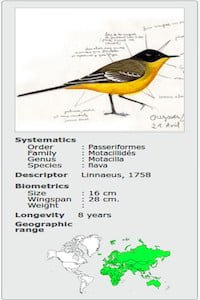

Sardina Pilchardus

– European Pilchard –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

| Scientific classification |

Sardina pilchardus

(Walbaum, 1792)[2]

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Clupeiformes |

| Family: | Clupeidae |

| Genus: | Sardina |

| Species: | S. pilchardus |

The European pilchard (Sardina pilchardus) is a species of ray-finned fish in the monotypic genus Sardina. The young of the species are among the many fish that are sometimes called sardines.[3][4] This common species is found in the northeast Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea at depths of 10–100 m (33–328 ft).[1] It reaches up to 27.5 cm (10.8 in) in length and mostly feeds on planktonic crustaceans.[2] This schooling species is a batch spawner where each female lays 50,000–60,000 eggs.[2]

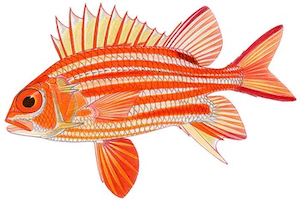

Description

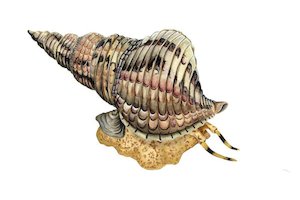

Sardina pilchardus is a fish of about twenty centimeters moving in schools.

Elongated and fusiform in shape, oval section, laterally compressed, it has a pointed muzzle and a terminal mouth.

The pectoral fins are low, the pelvic fins set behind the origin of the single dorsal fin. We note the absence of adipose fin.

The last two rays of its anal fin are longer than the others.

The European sardine has large scales for its size, easily detached, and a striated operculum *very characteristic. Scutes *, scales with a prominent point, are arranged along the ventral profile but do not form a true keel *.

She shows silvery sides and a relatively clear and shiny belly. Its emerald green, sometimes turquoise blue, back has iridescence as well as dark spots, along the lateral line, which are not always visible underwater.

After the fish dies, the color of the back changes from green to solid blue within a few hours.The upper parts are green or olive, the flanks are golden and the belly is silvery.[3]

Distribution and Habitat

The European pilchard occurs in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. Its range extends from Iceland and the southern part of Norway and Sweden southwards to Senegal in West Africa. In the Mediterranean Sea it is common in the western half and the Adriatic Sea, but uncommon in the eastern half and the Black Sea.[5] It is a migratory, schooling, largely coastal species but sometimes travels as far as 100 km (62 mi) out to sea. During the day it is mostly in the depth range 25 to 55 m (80 to 180 ft) but can go as deep as 100 m (330 ft). At night it is generally from 10 to 35 m (33 to 115 ft) beneath the surface.[1]

Ecology

European pilchard moves offshore in the autumn, preferring the deeper cooler waters and constant salinity out at sea to the variable temperatures and salinities of inshore waters. Spawning starts to take place in winter, and in early spring, juveniles, larvae and some adults move towards the coast, while other adults migrate inshore later in the year. Multiple batches of eggs are produced over a long breeding period, total fecundity being 50,000 to 60,000. Most juveniles become sexually mature at about a year old and a length of 13 to 14 cm (5.1 to 5.5 in); pilchards are fully grown at about 21 cm (8.3 in) when aged about eight years.[6]

Biotope

The European sardine is a pelagic * marine species, so it lives in open water in the seas and the ocean bordering the European continent. It is part of necton *, as opposed to plankton *, and lives from the coast to the open sea, between the surface and the bottom, up to about 100 m deep.

Due to their daily vertical migration, they are generally found more in depth during the day than at night.

Alimentation

Sardines are planktivorous * animals. They feed mainly on zooplankton * and more particularly on small planktonic crustaceans, the copepods ( Temora sp., Paracalanus sp.).

Although the presence of plants, phytoplankton *, has been observed in the digestive tract of some individuals, their consumption seems rather accidental. It is linked to the mode of feeding of the animal which feeds mainly by filtration. It moves with its mouth open, the preys being retained at the gills when the water comes out. Thus, non-animal preys can be eaten if they are retained by the gills.

Sardines have a rather nocturnal diet: they come to the surface during the night, following the vertical migration of zooplankton *, nycthemeral migration *, in order to feed on them.

The zooplankton is largely copepods and their larvae, which make daily vertical migrations to feed near the surface at night, and this is when the adult pilchards feed on them; juveniles feed during the day as well.[6] Along with the European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus), the European pilchard plays an important intermediate role in the Mediterranean ecosystem as a consumer of plankton and as a food for larger demersal predators such as the European hake (Merluccius merluccius) and the European conger eel (Conger conger). This role is particularly noticeable in the Adriatic Sea where the water is shallow, the food chain is shorter and energy is retained within the basin; overfishing of pilchard and anchovy can thus cause dramatic changes in the ecosystem.[6]

Reproduction

Sardines reach sexual maturity at a size of between 10 and 20 cm, depending on the population.

The main spawning period would be between October and June, with a peak between December and March. However, mature sardines and eggs are found more or less all year round on our coasts. The more individuals live in the south, the earlier and the longer the spawning period begins.

Breeding occurs on the continental shelf, mainly in coastal waters, richer in food and warmer, without there appearing to be a well-defined area.

The female can lay up to 60,000 eggs, less dense than water: they therefore rise to the surface.

Fertilization, external, takes place in water by the milt of the male. Once fertilized, the eggs hatch after 2 to 4 days to produce a larva * of about four millimeters.

Fisheries and Uses

There are important fisheries for this species in most of its range. It is mainly caught with purse seines and lampara nets, but other methods are also used including bottom trawling with high opening nets. In total, around a million tonnes are taken annually, with Morocco and Spain having the largest catches. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) considers the Moroccan fishery overfished.[5]

The adults may be sold as pilchards; the juveniles, as sardines.[3] The terms “sardine” and “pilchard” are not precise, and what is meant depends on the region. The United Kingdom’s Sea Fish Industry Authority, for example, classifies sardines as young pilchards.[7] One criterion suggests fish shorter in length than 15 cm (6 in) are sardines, and larger fish are pilchards.[8] The FAO/WHO Codex standard for canned sardines cites 21 species that may be classed as sardines.[4]

The fish is sold fresh, frozen or canned, or is salted and smoked or dried; as the flesh is of low value, some of the catch is used for fishing bait, fertilizer and some is manufactured into fish meal.[1]

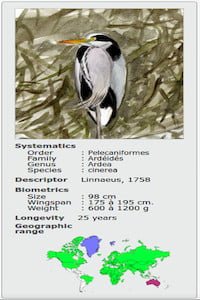

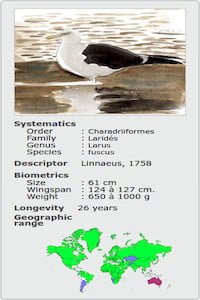

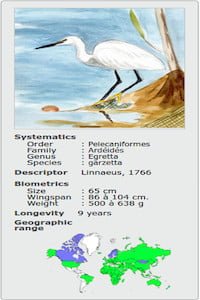

Associated Life

Sardina pilchardus is a forage species, that is to say it is the prey of many other marine species (birds, marine mammals, other fish). It therefore represents a major ecological interest: it feeds at the origin of marine food chains, on plankton, and it is a source of food for many predators.

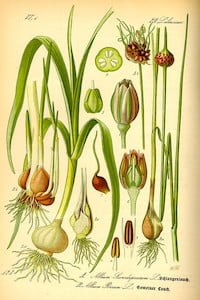

Similar Species

The European sardine can theoretically only be confused with the young shad, Alosa spp. due to its striated operculum. It is distinguished from it by the last two rays of its anal fin which are longer than the others and by the posterior end of its mouth located in front of the vertical passing through the center of the eye.

However, in diving, it is possible to confuse it with other Clupeidae such as sprats, Sprattus sprattus ; the implantation of the pelvic fins makes it possible to differentiate them: clearly behind the origin of the dorsal fin in sardines and in front or in line with the dorsal fin in sprat.

The anchovies are distinguished by their prominent snout and wide mouth very back.

Herrings, Clupea harengus , have significantly smaller, firmly established scales and pelvic fins anterior to the dorsal.

Sardinellae , Sardinella aurita , in the Mediterranean, show a yellow longitudinal line all the way down the body.

The silversides as sauclet , have two dorsal fins and swim in bursts, unlike the sardines that swim is called “rippling” or even “zigzagging” when they feed.

Les chinchards ont eux aussi deux nageoires dorsales et une ligne latérale très marquée en forme de “baïonnette”.

Les bogues, Boops boops, présentent de gros yeux, et un profil de tête plus arrondi. Ils apparaissent plus argentés dans l’eau que la sardine, vert émeraude ou turquoise.

Further Information

Sardine fishing has been of paramount economic importance for centuries along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. It supplies a large fresh fish market and canneries.

It is an inshore fishery, the boats rarely stay at sea for more than 12 hours, and possibly seasonal.

Like all fatty fish, sardines do not tolerate freezing well. They must be kept in ice, and landed quickly, or salted, as was done in the 19th century.

The original straight gillnet is replaced by the purse seine and purse seine (the purse seine) and, more incidentally, the pelagic trawl.

In the past century, this fishery has resulted in the construction of specific boats, such as the Breton sardine boats or the Arcachonnaise and Luzian pinnacles.

At the start of the 20th century, Douarnenez and Concarneau were the first sardine ports. In the middle of the century, the schools of sardines migrated further south, deserting Brittany.

Around 1950, around 30,000 people made a living from fishing and canning on the Atlantic coast. During this period, the main sardine ports were La Turballe, St Gilles-Croix-de-Vie and St Jean-de-Luz in the Atlantic, and Sète, Marseille and Port-Vendres in the Mediterranean.

The annual catches in France were then of the order of 30,000 tonnes, half in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. In Morocco, they reached 220,000 tonnes.

However, in 1983, barely 5,000 tonnes were officially landed by the French fisheries in the Bay of Biscay. Despite the fluctuation in the number of catches from year to year – due to significant variability in stocks, which are very sensitive to overfishing and environmental conditions for recruitment * – catches have increased overall, reaching 20,000 tonnes in 2009 in the Atlantic for France. In the Mediterranean, they have obviously never exceeded 5,000 tonnes for France since 1993.

Every year since 1983, IFREMER has been monitoring stocks of sardines and other small pelagic fish in the French part of the Bay of Biscay, in particular thanks to the PELGAS oceanographic surveys (from 2000, from the end of April to the beginning of June), with the research La Thalassa . Professional fishing boats have also participated in this campaign for a few years, working in concert with scientists. This sharing of knowledge and skills allows, among other things, to improve the quality of expertise carried out on fishery resources. In the Mediterranean, similar missions (PELMED) are also carried out every year from 1993, between the end of June and the beginning of August, on board the oceanographic vessel L’Europe .

Currently, IFREMER estimates the sardine biomass in the Bay of Biscay between 300,000 and 500,000 tonnes. On the other hand, in the Gulf of Lion, it has fallen sharply since 2005 (from over 200,000 tonnes in 2005 to less than 50,000 in 2010), with the decline in spawners in particular: their biomass is estimated at less than 5 000 tonnes for 2010. The fisheries were forced to restrict their activity at the end of 2009 pending a recovery of stocks.

In the Alpes-Maritimes, highly traditional and emblematic, fishing for poutine ( poutina in nissart) and nonat (meaning “not born”) is exclusively authorized in the prud’homies of Antibes, Cros-de-Cagnes, Nice and Menton. Very few fishermen still practice this fishing for fry, mainly sardines, still quite transparent. Depending on the weather, fishing stops as soon as the first scales appear on the fish.

In fact, poutine fishing is highly regulated by the European Parliament’s “Fishing” Commission, which conditions it with a standardized mesh size and restricts it to very specific harvest dates, generally beginning in the middle of January and for 45 days.

While until the 1960s, the sale was carried out on hand carts parked in the alleys of the old town, to the bantering cries of the fishmongers ” A la bella poutina !!” », The fruit of the peach is now generally sold directly on the beach, when the pointus is brought up and barely out of the nets. The price is quite high (more than 60 € / kg in 2012). A rare and popular dish among locals, poutine can be enjoyed as an omelet or donuts, even for connoisseurs with a simple drizzle of olive oil and lemon.

From an environmental point of view and conservation of resources, it is better to favor for our food the species located relatively low in the food webs (Clupeidae, mules) than the large predators (tuna, swordfish, sharks and rays), less numerous and with less important reproductive capacities: late sexual maturity, fewer descendants. Not to mention that the latter generally have very high levels of heavy metals and other contaminants compared to fodder species.

Sardine is therefore one of the interesting species to include in our diet.