Pterois Volitans

– Red Lionfish –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

| Scientific classification |

Pterois volitans (Linnaeus, 1758)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scorpaeniformes |

| Family: | Scorpaenidae |

| Genus: | Pterois |

| Species: | P. volitans |

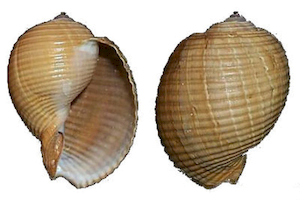

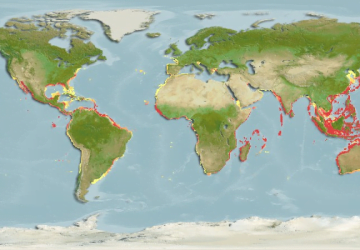

The red lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a venomous coral reef fish in the family Scorpaenidae, order Scorpaeniformes. It is mainly native to the Indo-Pacific region, but has become an invasive species in the Caribbean Sea, as well as along the East Coast of the United States and East Mediterranean.

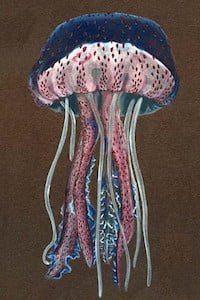

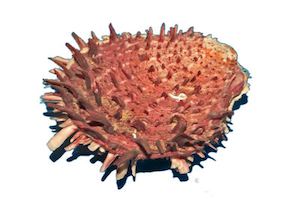

P. volitans and a similar relative, Pterois miles, have both been deemed invasive species. Red lionfish are clad in white stripes alternated with red/maroon/brown stripes. Adults in this species can grow as large as 47 cm (18.5 in)[2] in length, making it one of the largest species of lionfish in the ocean, while juveniles are typically shorter than 1 inch (2.5 cm).[3] The average red lionfish lives around 10 years.[4] As with many species within the family Scopaenidae, it has large, venomous spines that protrude from the body, similar to a mane, giving it the common name lionfish. The venomous spines make the fish inedible or deter most potential predators. Lionfish reproduce monthly and are able to quickly disperse during their larval stage for expansion of their invasive region. No definitive predators of the lionfish are known, and many organizations are promoting the harvest and consumption of lionfish in efforts to prevent further increases in the already high population densities.

Description

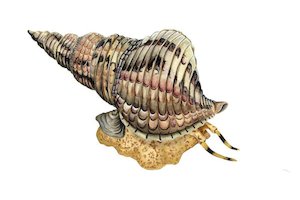

The Pacific lionfish can reach 38 cm . The massive body has alternating white vertical stripes and red to dark brown stripes . Small white spots along the lateral line are sometimes present. The scales are cycloid *. The mouth is wide. Skin flaps are present on the muzzle, usually more developed on the lower jaw. Most of the time, we note the presence of an appendix erect above each eyewhich evolve over time: juveniles have thin and straight “antennae”; young adults develop characteristically shaped leafy appendages, with an ocellus near the tip, and older adults gradually lose these eye appendages (it is during this process that an appendix can be seen on one eye and not on the ‘other).

The thorny part of the dorsal fin (13 spines) and the pectoral ones consist of very long free spines , with a veil running over their entire length . The flexible part of the dorsal fin (10-11 soft rays) as well as the caudal and anal are transparent dotted with brown .

The juveniles are very dark , almost black, with pectoral fins more developed than those of adults.

This description is also valid for the species Pterois miles (Bennett, 1828), the lionfish of the Indian Ocean, morphologically identical to P. volitans . We then speak of the Pterois volitans / miles complex .

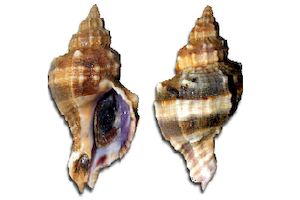

Similar Species

It is virtually indistinguishable from Pterois volitans from P. miles with the naked eye. The latter replaces P. volitans in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea (according to some authors in the Red Sea it would even be a distinct species, P. muricata ). It is a Lessepsian * species that is also found in the eastern part of the Mediterranean. These 2 species were long considered to be a simple geographic variation of P. volitans , but today genetic studies have shown differences and they are recognized as 2 distinct species.

Pterois russelli has a similar appearance but is differentiated from P. volitans by a deeper biotope, paler coloration and absence of punctuation on the soft rays of the dorsal, caudal and anal.

There are other species in the genus Pterois (such as P. antennata , P. radiata , P. mombassae ), but only P. volitans has pectoral fins with free rays and a large veil over their entire length. Finally, the genus Dendrochirus is also quite close, but the fin rays are shorter and the pectoral rays are connected by a membrane.

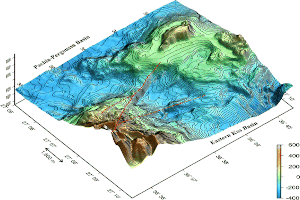

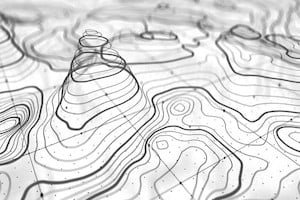

Biotope

Pterois volitans occurs in lagoons and outer slopes, between the surface and 55 m depth. In estuaries and murky waters, its coloring is darker. During the day, these fish are found under overhangs and dark places, where they stay against the vertical wall or upside down, against the ceiling. At night, they go out to hunt. It is very common to observe these scorpion fish in wrecks.

Alimentation

The Pacific lionfish feeds on fish and crustaceans, which it hunts mainly at night by knocking them down in a corner thanks to its long pectorals. When a prey is within reach, it snaps its huge protractile mouth * to swallow it.

Reproduction

They are mainly a solitary species and courting is the only time they aggregate, generally one male with several females.[4] Both P. volitans and P. miles are gonochoristic, only showing sexual dimorphism during reproduction. Similar courtship behaviors are observed in all Pterois species, including circling, sidewinding, following, and leading. The lionfish are mostly nocturnal, leading to the behaviors typically around nightfall and continuing through the night. After courtship, the female releases two egg masses, fertilized by the male before floating to the surface. The embryos secrete an adhesive mucous allowing them to attach to nearby intertidal rocks and corals before hatching. During one mating session, females can lay up to 30,000 eggs. However, it has been observed that females will lay more eggs in the warmer months.[6]

The sexes are separate and reproduction is external, in open water. It takes place at night, 6 to 8 females regrouping for a single male. It is an ovuliparous * fish. A female can lay up to 40,000 eggs, which are clustered by the thousands in small balls of mucus. Over the days, this mass of mucus breaks down, gradually releasing the eggs. The larvae hatch after a few days and drift for 3 to 4 weeks in the current. Pelagic juveniles can therefore swarm over very large distances.

Various Biology

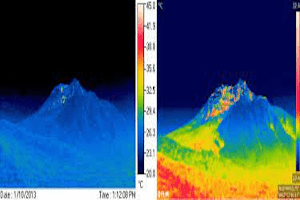

The coloring of the Pacific lionfish is variable, more or less dark. Depending on the biotope, the same individual can change color in a few minutes.

It is a solitary fish but which is sometimes found in small groups.

The maximum reported age of this species is 10 years.

Distribution

P. volitans is native to the Indo-Pacific region,[5] including the western and central Pacific and off the coast of western Australia. However, the species has been accidentally introduced into the Western Atlantic, becoming an invasive species there and in the northern Gulf of Mexico as well.

Life History

Early life history and dispersal

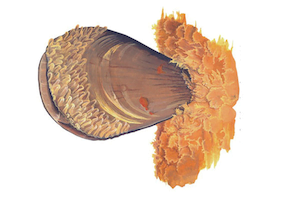

Although little is known about the larval stage of the lionfish, some traits of the larvae include a large head, a long, triangular snout, long, serrated head spines, a large pelvic spine, and coloration only in the pelvic fins. Larvae hatch 36 hours after fertilization.[4] They are good swimmers and can eat small ciliates just four days after conception.[4] The larval stage is the shortest stage of the lionfish’s life, with a duration of about one month.[7]

Venom

Lionfish venomous dorsal spines are used purely for defense.[disputed – discuss] When threatened, the fish often faces its attacker in an upside-down posture which brings its spines to bear. However, its sting is usually not fatal to humans. Envenomed humans will experience extreme pain, and possibly headaches, vomiting, and breathing difficulties. A common treatment is soaking the afflicted area in hot water, as very few hospitals carry specific treatments.[8][9][10] However, immediate emergency medical attention is strongly recommended, as some people are more sensitive to the venom than others.

As an invasive species

Two of the 15 species of Pterois, P. volitans and P. miles, have established themselves as significant invasive species off the East Coast of the United States and in the Caribbean. About 93% of the invasive lionfish population is the red lionfish.[11] The red lionfish was likely first introduced off the Florida coast in the early to mid-1980s,[12] almost certainly from the aquarium trade.[13] Adult lionfish specimens are now found along the East Coast from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Florida, and in Bermuda, the Bahamas, and throughout the Caribbean, including the Turks and Caicos, Haiti, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, Belize, Honduras, Aruba, Cayman Islands, Colombia and Mexico.[14]

Predators and Prey

In its invasive range, few predators of the lionfish have been documented. Most larger Atlantic and Caribbean fish and sharks that should be able to eat the lionfish have not recognized them as prey, likely due to the novelty of the fish in the invaded areas. Lionfish have, however, been found in the stomachs of Nassau and tiger groupers in the Bahamas,[15] but the former is critically endangered and therefore highly unlikely to provide significant predation. In its native range, two species of moray eels were found preying on lionfish.[16] The Bobbit worm, an ambush predator, has been filmed preying upon lionfish in Indonesia;[17] similar species inhabit the Caribbean.

The lionfish themselves are voracious feeders and have outcompeted and filled the niche of the overfished snapper and grouper. When hunting, they corner prey using their large fins, then use their quick reflexes to swallow the prey whole. They hunt primarily from late afternoon to dawn. High rates of prey consumption, a wide variety of prey, and increasing abundance of the fish lead to concerns the fish may have a very active role in the already declining trend of fish densities.[18] As the fish become more abundant, they are becoming a threat to the fragile ecosystems they have invaded. Between outcompeting similar fish and having a varied diet, the lionfish is drastically changing and disrupting the food chains holding the marine ecosystems together. As these chains are disrupted, declining densities of other fish populations are found, as well as declines in the overall diversity of coral reef areas.

Further Information

Like most lionfish, the Pacific lionfish has a pair of venom glands incorporated into each spiny ray of its dorsal, anal, and pelvic fins. The sting is very painful and even fatal in rare cases. The venom is heat sensitive and can be destroyed by a heat source. An application of corticosteroids reduces the inflammatory reaction caused by this toxin.

Therefore, this species has practically no predator. The best known, strangely enough, is the pipefish Fistularia commersonii . We can also mention the moray eels. In Honduras, experiments are being carried out to “train” sharks to feed on lionfish!

It is a little shy fish that does not hesitate to follow the divers in night diving, throwing themselves on the small fish lit by the lamps.

To fight against its proliferation in the Caribbean, a brochure with many recipes for the lionfish, whose flesh is very good, has been published!