Monachus Monachus

– Mediterranean Monk Seal –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Endangered (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

Endangered (ESA)[2] |

| Scientific classification |

Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipediformes |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Phocidae |

| Genus: | Monachus Fleming, 1822 |

| Species: | M. monachus |

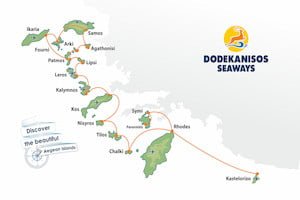

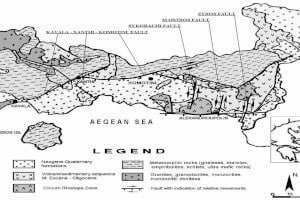

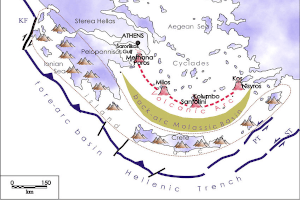

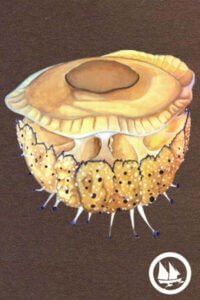

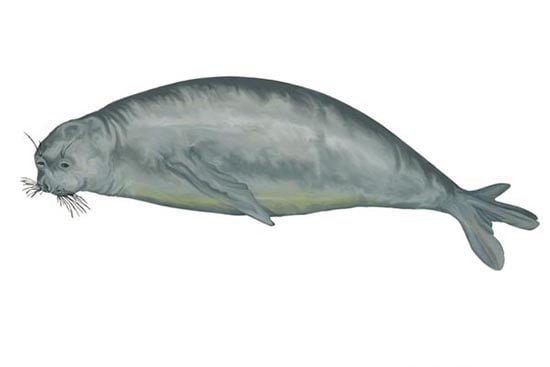

The Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) is a monk seal belonging to the family Phocidae. As of 2015, it is estimated that fewer than 700 individuals survive in three or four isolated subpopulations in the Mediterranean, (especially) in the Aegean Sea, the archipelago of Madeira and the Cabo Blanco area in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean.[3] It is believed to be the world’s rarest pinniped species.[1]

Description

This species of seal grows from approximately 80 centimetres (2.6 ft) long at birth up to an average of 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) as adults, females slightly shorter than males.[4] Males weigh an average of 320 kilograms (710 lb) and females weigh 300 kilograms (660 lb), with overall weight ranging from 240–400 kilograms (530–880 lb).[1][5][6][7] They are thought to live up to 45 years old;[5] the average life span is thought to be 20 to 25 years old and reproductive maturity is reached at around age four.

The monk seals’ pups are about 1 metre (3.3 ft) long and weigh around 15–18 kilograms (33–40 lb), their skin being covered by 1–1.5 centimeter-long, dark brown to black hair. On their bellies, there is a white stripe, which differs in color and shape between the two sexes. In females the stripe is usually rectangular in shape whereas in males it is usually butterfly shaped.[8] This hair is replaced after six to eight weeks by the usual short hair adults carry.[5] Adults will continue to molt annually, causing their color vibrancy to change throughout the year. [9]

Pregnant Mediterranean monk seals typically use inaccessible undersea caves while giving birth, though historical descriptions show they used open beaches until the 18th century. There are eight pairs of teeth in both jaws.

Believed to have the shortest hair of any pinniped, the Mediterranean monk seal fur is black (males) or brown to dark grey (females), with a paler belly, which is close to white in males. The snout is short broad and flat, with very pronounced, long nostrils that face upward, unlike their Hawaiian relative, which tend to have more forward nostrils. The flippers are relatively short, with small slender claws. Monk seals have two pairs of retractable abdominal teats, unlike most other pinnipeds.

Habitat

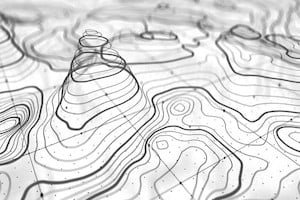

The habitat of this pinniped has changed over the years. In ancient times, and up until the 20th century, Mediterranean monk seals had been known to congregate, give birth, and seek refuge on open beaches. In more recent times, they have left their former habitat and now only use sea caves for these activities. Often these caves are inaccessible to humans. Often their caves have underwater entries and their caves are often positioned along remote or rugged coastlines.

Scientists have confirmed this is a recent adaptation, most likely due to the rapid increase in human population, tourism, and industry, which have caused increased disturbance by humans and the destruction of the species’ natural habitat. Because of these seals’ shy nature and sensitivity to human disturbance, they have slowly adapted to try to avoid contact with humans completely within the last century, and, perhaps, even earlier. The coastal caves are, however, dangerous for newborns, and are causes of major mortality among pups when sea storms hit the caves.

Alimentation

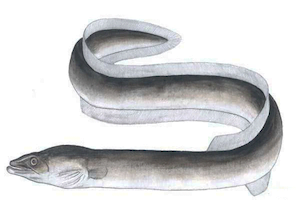

Mediterranean monk seals are diurnal and feed on a variety of fish and mollusks, primarily octopus, squid, and eels, up to 3 kg per day. Although they commonly feed in shallow coastal waters, they are also known to forage at depths up to 250 meters, with an average depth varying between specimens.[1] Monk seals prefer hunting in wide-open spaces, enabling them to use their speed more effectively. They are successful bottom-feeding hunters; some have even been observed lifting slabs of rock in search of prey.

Reproduction

Very little is known of this seal’s reproduction. Scientists have suggested that they are polygynous, with males being very territorial where they mate with females. Although there is no breeding season since births take place year round, there is a peak in September, October, and November. Although mating will take place in the water, females will give birth and care for the pups on beaches or underwater caves. The use of underwater caves may have began in order to make predatory actions almost impossible as these caves are difficult to access. Because they will stay with the pups to nurse and protect, using their stored fat reserves to nurse. [4] Data analysis indicates that only 29% of pups born between September and January survive. One cause of this low survival rate is the timing of high surf around the areas of breeding, creating a threat to young pups. As well, because of smaller populations there is an increase in genetic events such as inbreeding and lack of genetic variation. During other months of the year, pups have an estimated survival rate of 71%.[10]

In 2008, lactation was reported in an open beach, the first such record since 1945, which could suggest the seal could begin feeling increasingly safe to return to open beaches for breeding purposes in Cabo Blanco.[11]

Pups make first contact with the water two weeks after their birth and are weaned at around 18 weeks of age; females caring for pups will go off to feed for an average of nine hours.[1] Most female individuals are believed to reach maturity at four years of age unto which they will begin to breed. [4] Males begin to breed at age six. [9] The gestation period lasts close to a year. However, it is believed to be common among monk seals of the Cabo Blanco colony to have a gestation period lasting slightly longer than a year.[citation needed]

Status

This earless seal‘s former range extended throughout the Northwest Atlantic Africa, Mediterranean and Black Sea coastlines, including all offshore islands of the Mediterranean, and into the Atlantic and its islands: Canary, Madeira, Ilhas Desertas, Porto Santo… as far west as the Azores. Vagrants could be found as far south as Gambia and the Cape Verde islands, and as far north as continental Portugal and Atlantic France.[1]

Several causes provoked a dramatic population decrease over time: on one hand, commercial hunting (especially during the Roman Empire and Middle Ages) and, during the 20th century, eradication by fishermen, who used to consider it a pest due to the damage the seal causes to fishing nets when it preys on fish caught in them; and, on the other hand, coastal urbanization and pollution.[1]

Some seals have survived in the Sea of Marmara,[12] but the last report of a seal in the Black Sea dates to 1997.[1] Monk seals were present at Snake Island until the 1950s, and several locations such as the Danube Plavni Nature Reserve [ru] and Doğankent were the last known hauling-out sites post-1990.[13]

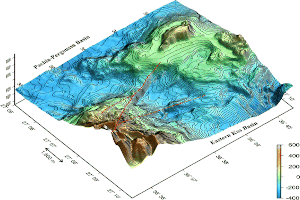

Nowadays, its entire population is estimated to be less than 700 individuals widely scattered, which qualifies this species as endangered. Its current very sparse population is one more serious threat to the species, as it only has two key sites that can be deemed viable. One is the Aegean Sea (250–300 animals in Greece, with the largest concentration of animals in Gyaros island,[3] and some 100 in Turkey); the other important subpopulation is in the Atlantic Ocean, in the Western Saharan portion of Cabo Blanco (around 270 individuals which may support the small, but growing, nucleus in the Desertas Islands – approximately 30-40 individuals[14]). There may be some individuals using coastal areas among other parts of Western Sahara, such as in Cintra Bay.[15]

These two key sites are virtually in the extreme opposites of the species’ distribution range, which makes natural population interchange between them impossible. All the other remaining subpopulations are composed of less than 50 mature individuals, many of them being only loose groups of extremely reduced size – often less than five individuals.[1]

Other remaining populations are in southwestern Turkey and the Ionian Sea (both in the eastern Mediterranean). The species status is virtually moribund in the western Mediterranean, which still holds tiny Moroccan and Algerian populations, associated with rare sightings of vagrants in the Balearic Islands,[16] Sardinia, and other western Mediterranean locations, including Gibraltar.

In Sardinia the Mediterranean monk seal was last sighted in May 2007 and April 2010. The increase of sightings in Sardinia suggests that the seal occasionally inhabits the Central Eastern Sardinian coasts, preserved since 1998 by the National Park of Golfo of Orosei.[17][18][19]

Colonies on the Pelagie Islands (Linosa and Lampedusa) were destroyed by fishermen, which likely resulted in local extinction.[20]

Cabo Blanco 1997 die off and Recovery

Cabo Blanco, in the Atlantic Ocean, is the largest surviving single population of the species, and the only remaining site that still seems to preserve a colony structure.[1] In the summer of 1997, more than 200 animals[1] or two-thirds of its seal population were wiped out within two months, extremely compromising the species’ viable population. While opinions on the precise causes of this epidemic remain divided between a morbilivirus or, more likely, a toxic algae bloom,[1] the mass die-off emphasized the precarious status of a species already regarded as critically endangered throughout its range.

Numbers in this all-important location started a slow-paced recovery ever since. A small but incipient (up to 20 animals by 2009) sub-population in the area had started using open beaches. In 2009, for the first time in centuries, a female delivered her pup on the beach (open beaches is the optimal habitat for the survival of pups, but had been abandoned due to human disturbance and persecution in past centuries).[21]

Only by 2016 the colony had recovered to its previous population (about 300 animals). This was made possible by a recovery plan financed by Spain.[14] Also in 2016, a new record of births was set for the colony (83 pups).[14]

However, the threat of a similar incident, which could severely reduce or wipe out the entire population, remains.[22]

Recent sightings

In June 2009, there was a report of a sighting off the island of Giglio, in Italy.[23] On 7 January 2010, fishermen spotted an injured Mediterranean monk seal off the coasts of Tel Aviv, Israel. When zoo veterinarians arrived to help the seal, it had slipped back into the waters. Members of the Israel Marine Mammal Research and Assistance Center arrived at the scene and tried to locate the injured mammal, but with no success. This was the first sighting of the species in the region since Lebanese authorities claimed to have found a population of 10–20 other seals on their coasts 70 years earlier.[24] In addition, the seal was also sighted a couple of weeks later in the northern kibbutz of Rosh Hanikra.[25]

In April 2010, there was a report of a sighting off the island of Marettimo, in the Egadi Islands off the coast of Italy, in Trapani Province.[26] In November 2010, a Mediterranean monk seal, supposedly aged between 10 and 20, had been spotted in Bodrum, Turkey.[27] On 31 December 2010, the BBC Earth news[28] reported that the MOM Hellenic Society[29] had located a new colony of seals on a remote beach in the Aegean Sea. The exact location was not communicated so as to keep the site protected. The society was appealing to the Greek government to integrate the part of the island on which the seals live into a marine protected area.

On 8 March 2011, the BBC Earth news[30] reported that a pup seal had been spotted on 7 February while monitoring a seal colony on an island in the southwestern Aegean Sea. Soon after, it showed signs of weakness and it was taken to a rehabilitation centre to try to save it. The aim is to release it back into the wild as soon as it is strong enough. In April 2011, a monk seal was spotted near the Egyptian coast after long absence of the species from the nation.[31]

On 24 June 2011, the Blue World Institute of Croatia [32] filmed an adult female underwater in the northern Adriatic, off the island of Cres and a specimen of unverified sex on 29 June 2012.[33] On 2 May 2013 a specimen was seen on the southernmost point of Istrian peninsula near the town of Pula.[34] On 9 September 2013, in Pula a male specimen swam to a busy beach and entertained numerous tourists for five minutes before swimming back to the open sea.[35] In summer 2014 sightings in Pula have occurred almost daily and monk seal stayed multiple times on crowded city beaches, sleeping calm for hours just few meters away from humans.[36][37] To prevent accidents and preserve monk seal, local city council acquired special educational boards and installed on city beaches.[38] Despite clear instructions, an incident occurred with a tourist harassing a seal. The whole event was filmed.[39] Less than a month later on 25 August 2014 this female monk seal was found dead in the Mrtvi Puć bay near Šišan, Croatia. Experts said it was natural death caused by her old age.[40]

In 2012, a Mediterranean monk seal, was spotted in Gibraltar on the jetty of the private boat owners club at Coaling Island.[41]

In the week of 22–28 April 2013, what is believed to have been a monk seal was viewed in Tyre, southern Lebanon; photographs have been reported among many local media.[42] A study by the Italian Ministry of the Environment in 2013 confirmed the presence of monk seals in marine protected area in the Egadi Islands.[43] In September and October 2013, there were a number of sightings of an adult pair in waters around RAF Akrotiri in British Sovereign Base waters in Cyprus.

In November 2014, an adult monk seal was reportedly seen inside the port of Limassol, Cyprus. A female monk seal, called Argiro by the locals, was repeatedly seen on beaches of Samos island in 2014 and 2015,[44] and two were reported in April 2016.[45]

On 7 April 2015, a large floating “fish” was reported near Raouche, Beirut in Lebanon, and collected by a local fisherman. This turned out to be the body of a female monk seal known to have been resident there for some time. Further investigations revealed that she was pregnant with a pup.[46]

On 13 August 2015, ten monk seals were spotted in Governor’s Beach, Limassol, Cyprus.[47]

On 6 January 2016, a monk seal climbed aboard a parked boat in Kuşadası.[48]

On 10 April 2016, a monk seal was spotted and photographed by a group of foreign exchange students and local bio-engineers in a creek in Manavgat District in Turkey‘s southern Antalya Province. According to the scientists involved in local projects to protect the animals, this was the first ever documented sighting of a monk seal swimming in a river. Possible reasons for the animal’s appearance included better opportunities for hunting, as well as higher salinity levels due to lower water levels.[49]

On 26 April 2016, two monk seals were spotted at the municipal baths area of Paphos, Cyprus.[50]

On 18 October 2016, a monk seal was captured on video around Gulf of Kuşadası.[51]

On 3 November 2016, a monk seal was spotted at the coast of Gialousa in Cyprus.[52]

On 13 June 2017, a specimen was spotted and photographed by a group of fishermen off the coasts of Tricase in the south of Italy.[53]

In early 2018 a mother and her pup were spotted around Paphos Harbour in Cyprus.[54]

In November 2018, a young monk seal was spotted at the coast of Karavostasi in Cyprus, only to be found dead at the same area a few days later.[55]

On 15 March 2019, a monk seal was spotted and photographed by a group of citizens at a marina in Kuşadası.[56]

On 26 March 2019, a young monk seal and a mature one 1.5 meter were sighted in Vlora, Albania, in the Ionian sea.[citation needed]

On 20 July 2019, a monk seal was spotted in Protaras bay area in Cyprus .[57]

On 27 January 2020, a young monk seal was spotted in Apulia. Some day later, it was found dead in another beach.

Preservation

Damage inflicted on fishermen’s nets and rare attacks on off-shore fish farms in Turkey and Greece are known to have pushed local people towards hunting the Mediterranean monk seal, but mostly out of revenge, rather than population control. Preservation efforts have been put forth by civil organizations, foundations, and universities in both countries since as early as the 1970s. For the past 10 years[citation needed], many groups have carried out missions to educate locals on damage control and species preservation. Reports of positive results of such efforts exist throughout the area.[58]

In the Aegean Sea, Greece has allocated a large area for the preservation of the Mediterranean monk seal and its habitat. The Greek Alonissos Marine Park, that extends around the Northern Sporades islands, is the main action ground of the Greek MOm organisation.[59] MOm is greatly involved in raising awareness in the general public, fundraising for the helping of the monk seal preservation cause, in Greece and wherever needed. Greece is currently investigating the possibility of declaring another monk seal breeding site as a national park, and also has integrated some sites in the NATURA 2000 protection scheme. The legislation in Greece is very strict towards seal hunting, and in general, the public is very much aware and supportive of the effort for the preservation of the Mediterranean monk seal.

The complex politics concerning the covert opposition of the Greek government towards the protection to the monk seals in the eastern Aegean in the late 1970s is described in a book by William Johnson.[60] Oil companies apparently may have been using the monk seal sanctuary project as a stalking horse to encourage greater cooperation between the Greek and Turkish governments as a preliminary to pushing for oil extraction rights in a geopolitically unstable area. According to Johnson, the Greek secret service, the YPEA, were against such moves and sabotaged the project to the detriment of both the seals and conservationists, who, unaware of such covert motivations, sought only to protect the species and its habitat.

One of the largest groups among the foundations concentrating their efforts towards the preservation of the Mediterranean monk seal is the Mediterranean Seal Research Group (Turkish: Akdeniz Foklarını Araştırma Grubu) operating under the Underwater Research Foundation (Turkish: Sualtı Araştırmaları Derneği) in Turkey (also known as SAD-AFAG). The group has taken initiative in joint preservation efforts together with the Foça municipal officials, as well as phone, fax, and email hotlines for sightings.[61]

Preservation of the species requires both the preservation of land and sea, due to the need for terrestrial haul-out sites and caves or caverns for the animal to rest and reproduce. Even though responsible scuba diving instructors hesitate to make trips to known seal caves, the rumor of a seal sighting quickly becomes a tourist attraction for many. Irresponsible scuba diving trips scare the seals away from caves which could become habitation for the species.

The Environment and Urbanization Minister of Turkey announced on 18 November 2019 that a plan was proposed to further preserve the species to allow the sub species of Foça, Gökova, Datça and Bozburun to increase in numbers.[62]

Conservation

Under the auspices of the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) concerning Conservation Measures for the Eastern Atlantic Populations of the Mediterranean Monk Seal was concluded and came into effect on 18 October 2007. The MoU covers four range States (Mauritania, Morocco, Portugal and Spain), all of which have signed, and aims at providing a legal and institutional framework for the implementation of the Action Plan for the Recovery of the Mediterranean Monk Seal in the Eastern Atlantic.

As there are indications of small population increases in the subpopulations, as of 2015, the Mediterranean monk seal’s IUCN conservation status has been updated from critically endangered to endangered in keeping with the IUCN’s speed-of-decline criteria, with a recommendation for re-assessment in 2020.[1]