Scyllarides Latus

– Mediterranean Slipper Lobster –

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Infraorder: | Achelata |

| Family: | Scyllaridae |

| Genus: | Scyllarides |

| Species: | S. latus |

| Binomial name |

|---|

| Scyllarides latus (Latreille, 1802) [2] |

Scyllarides latus, the Mediterranean slipper lobster, is a species of slipper lobster found in the Mediterranean Sea and in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. It is edible and highly regarded as food, but is now rare over much of its range due to overfishing. Adults may grow to 1 foot (30 cm) long, are camouflaged, and have no claws. They are nocturnal, emerging from caves and other shelters during the night to feed on molluscs. As well as being eaten by humans, S. latus is also preyed upon by a variety of bony fish. Its closest relative is S. herklotsii, which occurs off the Atlantic coast of West Africa; other species of Scyllarides occur in the western Atlantic Ocean and the Indo-Pacific. The larvae and young animals are largely unknown.

Description

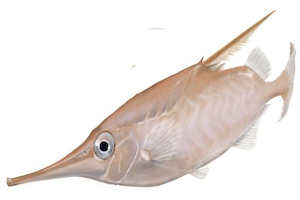

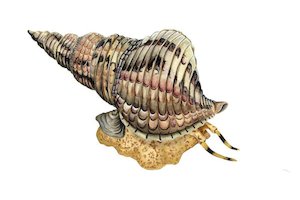

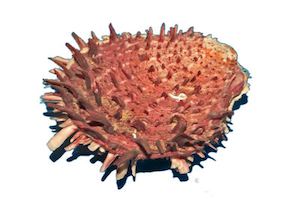

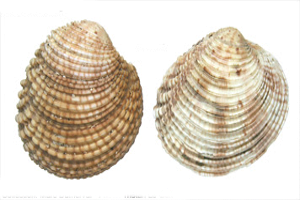

S. latus can grow to a total body length about 45 centimetres (18 in), although rarely more than 30 cm (12 in). This is equivalent to a carapace length of up to 12 cm (4.7 in).[2] An individual may weigh as much as 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb).[3] As in all slipper lobsters, the second pair of antennae are enlarged and flattened into “shovels” or “flippers“.[4] Despite the name “lobster”, slipper lobsters such as Scyllarides latus have no claws, and nor do they have the protective spines of spiny lobsters. Instead, the exoskeleton, and particularly the carapace, are thicker than in clawed lobsters and spiny lobsters, acting as resilient armour.[3] Adults are cryptically coloured, and the carapace is covered in conspicuous, high tubercles.[2]

The greater cicada looks like a lobster from a distance, but the body is stockier, dorso-ventrally flattened, and the antennae are flat, segmented paddles .

The carapace is more or less reddish brown, rough , grainy, bordered with purple at the antennae.

The length can reach 50 cm, commonly 25/30 cm . The legs are devoid of pincers, except the 5th pair in the female which uses it for the maintenance of the eggs which she carries under the abdomen.

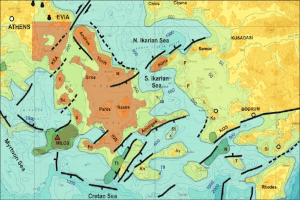

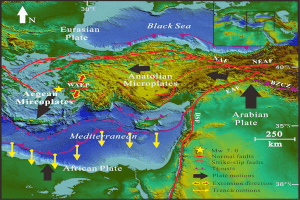

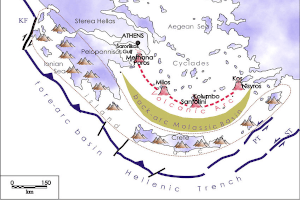

Distribution

Scyllarus latus is found along most of the coast of the Mediterranean Sea (one exception being the northern Adriatic Sea[3]), and in parts of the eastern Atlantic Ocean from near Lisbon in Portugal south to Senegal, including the islands of Madeira, the Azores, the Selvagens Islands and the Cape Verde Islands.[2] In Senegal, it occurs together with a related species Scyllarides herklotsii, which it closely resembles.[3]

Biotope

S. latus lives on rocky or sandy substrates at depths of 4–100 metres and likes caves, faults and the underside of isolated rock slabs in the Posidonia.

It is often found hanging under overhangs and the ceiling of cavities where it merges with the color of the substrate. Older adults, who rarely moult, can sometimes carry small algae or invertebrates (hydraires, bryozoa) attached to their shells, which further improves the quality of their camouflage.

They shelter during the day in natural dens, on the ceilings of caves, or in reefs, preferring situations with more than one entrance or exit.[3]

She goes out more readily at night.

Alimentation

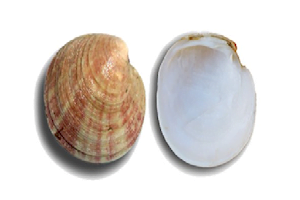

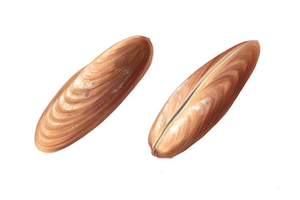

The diet of S. latus consists generally of molluscs. The preferred prey is, according to different sources, either limpets[2] or bivalves.[3] The prey, which S. latus can detect even under 3.5 cm (1.4 in) of sediment, is opened by careful use of the strong pointed pereiopods. They will also eat oysters and squid, but not sea urchins or muricidsnails. They eat more in warmer seasons, getting through 3.2 oysters per day in July, but only 0.2 oysters per day in January.[3]

They are occasionally scavengers *, and often get caught in traps and nets where they have entered to devour bait and caught fish.

Reproduction

Large cicadas breed from late spring through summer. We sometimes find gatherings of several dozen individuals, which return each year to very specific locations, sometimes at shallow depth, in caves, sheltered faults or in cavities of the coralligenous *.

The female carries her eggs hanging under the abdominal segments until they hatch.

The larvae * then have a planktonic life *, the duration of which is not well known. During this, they undergo several metamorphoses until the sub-adult stage where they will fall to the bottom.

Various biology

The genus of Scyllarids , created by Lund in 1793, currently comprises 13 species widespread throughout the world, more particularly in warm temperate seas.

– 7 in the Atlantic: S. aequinoctials, S. brasiliensis, S. deceptor, S. delfosi, S. herklotsii, S. latus, S. nodifer

– 4 in the Pacific: S. astori, S. haani, S. roggeveeni, S. squammosus

– 2 in the Indian Ocean: S. elisabethae, S. tridacnophaga.

All are relatively large and edible, although their catch is mostly incidental.

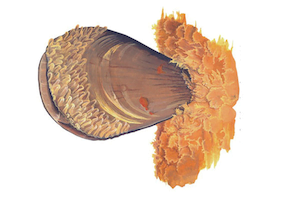

Life cycle

Male Scyllarus latus carry spermatophores at the base of the last two pairs of pereiopods in April.[3] Fertilisation has not been observed in this species, but most reptant decapods mate with the ventral surfaces together.[5] Between July and August, females carry around 100,000 eggs on their enlarged, feathery pleopods. The eggs develop from being a bright orange colour to a dark brown before being shed into the water after around 16 days of development. There is normally only one generation per year.[3]

The larvae are much less well known than the adults. An initial 1.3 millimetres (0.05 in) long naupliosoma stage, which swims using its antennae, moults into the first of eleven phyllosoma stages, which swim using their thoracic legs.[6] The last phyllosoma stage may reach a size of 48 mm (1.9 in) and can be up to 11 months old; most of the intermediate phyllosoma stages have not been observed.[3] A single nisto (juvenile has been recorded, having been caught off Reggio Calabria in 1900, but only recognised as being a juvenile S. latus in 2009.[7] Young adults are also rare; a museum specimen with a carapace length of 34 mm (1.3 in) is the smallest adult yet observed. Adults moult annually, and probably migrate to cooler waters with a temperature of 13–18 °C (55–64 °F) to do so. The old exoskeleton softens over a period of 10–22 days before being shed, and the new, pale exoskeleton takes around three weeks to harden completely. Smaller individuals typically gain weight over the course of a moult, but this difference is less pronounced in larger animals.[3]

Behaviour

Scyllarides latus is mostly nocturnal in the wild, since most of its predators are diurnal. While sheltering, S. latus tends to be gregarious, with several individuals sharing the same shelter. When confronted with a predator, S. latus has no claws or spines to repel the predator, and instead either clings to the substrate, or swims away with powerful flexion of the abdomen, or “tail-flips”. Larger lobsters can exert a stronger grip than smaller ones, with a force of up to 150 newtons (equivalent to a weight of 15 kilograms or 33 pounds) required to dislodge the largest individuals.[3]

Predator avoidance may also explain the frequent behaviour where S. latus will carry food items back to a shelter before consuming them. When two S. latus individuals compete for a food item, they may use the enlarged second antennae to flip their opponent over, by wedging the antennae underneath the opponent’s body and quickly raising them. An alternative strategy is to grip an opponent and begin the tail-flipping movement, or to engage in a tug of war.[3]

Taxonomy

Scyllarides latus was originally classified in the genus Scyllarus, along with the four other slipper lobsters known at the time (Scyllarus arctus, Scyllarides aequinoctialis, Thenus orientalis and Arctides guineensis). Separate genera were first introduced by William Elford Leach in 1815, namely Thenus and Ibacus. In 1849, Wilhem de Haan divided the genus Scyllarus into two genera, Scyllarus and Arctus, but made the error of including the type species of Scyllarus in the genus Arctus. This was first recognised by the ichthyologist Theodore Gill in 1898, who synonymised Arctus with Scyllarus, and erected a new genus Scyllarides to hold the species that De Haan had placed in Scyllarus.[8] Scyllarides is placed in the subfamily Arctidinae, which is differentiated from other subfamilies by the presence of multiarticulated exopods on all three maxillipeds, and a three-segmented palp on the mandible. The only other genus in the subfamily, Arctides, is distinguished by having a more highly sculptured carapace, with an extra spine behind each eye, and a transverse groove on the first segment of the abdomen.[9]

The only other species of Scyllarides to occur in the Eastern Atlantic is Scyllarides herklotsii, which differs from S. latus mostly in the ornamentation on the carapace; while in S. latus the tubercles (lumps projecting from the surface) are high and pronounced, they are lower and more rounded in S. herklotsii.[10]

Type specimen

The type locality given by Pierre André Latreille in his original description of the species was simply “Mediterranée” (Mediterranean Sea), without designating a type specimen. Lipke Holthuis later chose a lectotype for the species, which was the animal illustrated by Cornelius Sittardus, and published in Conrad Gesner’s Historiae animalium in 1558 (book 4, p. 1097).[2] This illustration, originally a watercolour but reproduced by Gesner in a woodcut, had been mentioned by Latreille in his description as being particularly fine, and is all that remains of the type specimen.[11] Given that Sittardus was working in Rome at the time, it is likely that the type specimen was a fresh specimen from the Tyrrhenian Sea near Rome.[11]

Predators

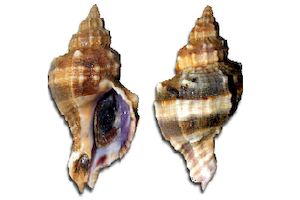

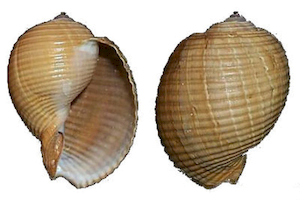

Similar Species

Scyllarides herklotsii (Herklots, 1851) the red cicada : present, supposedly rare in the Mediterranean, although few divers can differentiate it from S. latus , it is especially encountered in West Africa where the two species coexist. Quite difficult to distinguish from S. latus . One of the most remarkable differences is the presence of three red spots, clearly separated on the joint between the cephalothorax * and the abdomen.

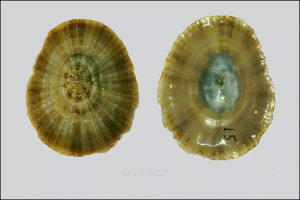

Scyllarus arctus , (Linnaeus, 1758) the little cicada has a different range from its larger cousin. It is found from the Mediterranean to the southern coasts of England to the north and on the Moroccan coasts to the south. Darker in color, its carapace is smoother, its antennae more indented on the edges, the eye peduncle and the legs are ringed in yellow. It often lives on mudder bottoms or among Posidonia meadows. Its size hardly exceeds 100 to 110 mm.

Scyllarus pygmaeus , (Bate, 1888) the dwarf cicada , much rarer, is sometimes confused with S. arctus , but its red or reddish brown color striped with white is very characteristic. It is mainly present on the northern coasts of the Mediterranean basin, in Gibraltar and the Canary Islands. Average size 40 to 60 mm.

The most significant predator of S. latus is the grey triggerfish, Balistes capriscus, although a number of other fish species have also been reported to prey on S. latus, including dusky groupers (Epinephelus guaza), combers (Serranus spp.), Mediterranean rainbow wrasse (Coris julis), red groupers (Epinephelus morio) and gag groupers (Mycteroperca microlepis).[3] An Octopus vulgaris has been observed to eat S. latus in an artificial setting, but it is unclear whether S. latus is preyed on by octopuses in nature.[3]

Human consumption

S. latus is edible, but it is a relatively rare species, and is therefore of little interest to fisheries. However, it is caught in small numbers throughout its distribution, mostly in trammel nets, by trawling and in lobster pots. An annual catch of 2,000–3,000 kg (4,400–6,600 lb) has been reported for Israel. Catching by hand has become increasingly frequent, since the advent of SCUBA diving made the animal’s habitat more accessible to humans. This may have affected population sizes of S. latus in some areas.[2]

Further Information

Always rare, but sought after for its delicate flesh, the big cicada has been the subject of intensive fishing by divers, whether they are snorkeling or scuba, in most countries of the Mediterranean and on the Atlantic coasts of the Iberian Peninsula.

Its main predators, apart from humans, are fish: groupers, dentis, triggerfish and octopuses.

His only defense is stealth, which justifies his nocturnal lifestyle and his daytime residence in caves and under rocks.

Despite its apparent slowness, the great cicada is capable of rapid reactions and can flee by swimming backwards at high speed!

It is not rare to find large cicadas in Rungis in the arrivals of red cicadas (Scyllarides herklotsii ) from West Africa.