Nephrops Norvegicus

– Norway Lobster –

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Family: | Nephropidae |

| Genus: | Nephrops |

| Species: | N. norvegicus |

| Binomial name |

|---|

| Nephrops norvegicus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Synonyms[2] |

| Cancer norvegicus Linnaeus, 1758 Astacus norvegicus Fabricius, 1775 Homarus norvegicus Weber, 1795 Astacus rugosus Rafinesque, 1814 Nephropsis cornubiensis Bate & Rowe, 1880 |

Nephrops norvegicus, known variously as the Norway lobster, Dublin Bay prawn, langoustine (compare langostino) or scampi, is a slim, orange-pink lobster which grows up to 25 cm (10 in) long, and is “the most important commercial crustacean in Europe”.[3] It is now the only extant species in the genus Nephrops, after several other species were moved to the closely related genus Metanephrops. It lives in the north-eastern Atlantic Ocean, and parts of the Mediterranean Sea, but is absent from the Baltic Sea and Black Sea. Adults emerge from their burrows at night to feed on worms and fish.

Description

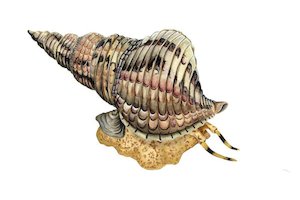

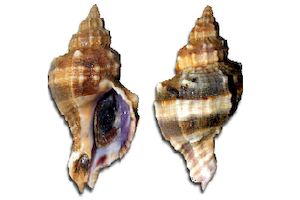

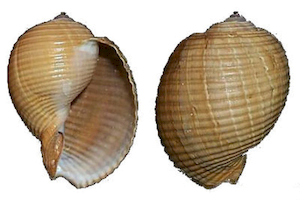

Nephrops norvegicus has the typical body shape of a lobster, albeit narrower than the large genus Homarus.[3] It is pale orange in colour, and grows to a typical length of 18–20 centimetres (7–8 in), or exceptionally 25 cm (10 in) long, including the tail and claws.[4] A carapace covers the animal’s cephalothorax, while the abdomen is long and segmented, ending in a broad tail fan.[4] The first three pairs of legs bear claws, of which the first are greatly elongated and bear ridges of spines.[4] Of the two pairs of antennae, the second is the longer and thinner.[4] There is a long, spinous rostrum, and the compound eyes are kidney-shaped, providing the name of the genus, from the Greek roots νεφρός (nephros, “kidney”) and ops (“eye”).[3]

The sides and top of the shell * can vary from orange to flesh pink and are sometimes finely speckled with orange or red. The underside of the shell is lighter, it is generally tinged with a more or less translucent yellowish white.

The body of Nephrops norvegicus can be broken down into three parts.

– The cephalon * (the head), which has two large black kidney-shaped eyes at the end of two white peduncles *. It ends with a long pointed rostrum * framed by two pairs of antennae (a small pair on the center side and a long pair on the outer side).

– The thorax is the part of the body that carries the legs and claws. The langoustine has two main claws as long as its body , and on which stand rows of small white spines. These two pincers are accompanied by 4 pairs of long and thin walking legs (pereiopods *), of whichthe ends of the first two pairs are terminated with small pliers .

The head and the thorax are united and form the cephalothorax *, it is covered by the same portion of shell.

– Finally the abdomen , it is made up of 6 cartilaginous and articulated segments which form the edible part of the langoustine. Each of the first 5 segments has two small articulated appendages, the pleopods *. It is these appendages that carry the eggs when the female is seeded, they are then constantly agitated to promote oxygenation of the eggs. The 6 thpair of pleopods (the uropods *) form with the suchon * the tail of the langoustine. This tail allows it to flee quickly by swimming backwards when it is faced with danger.

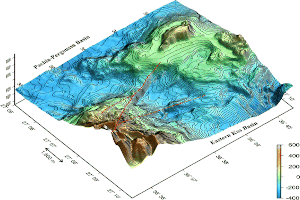

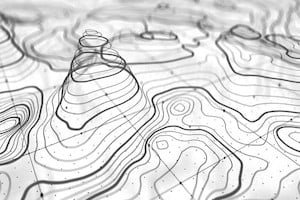

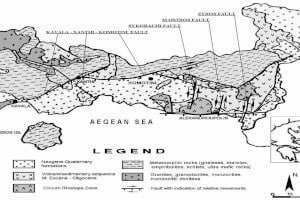

Distribution

Nephrops norvegicus is found in the north-eastern Atlantic Ocean and North Sea as far north as Iceland and northern Norway, and south to Portugal. It is not common in the Mediterranean Sea except in the Adriatic Sea,[5] notably the north Adriatic.[6] It is absent from both the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea.[3] Due to its ecological demands for particular sediments, N. norvegicus has a very patchy distribution, and is divided into over 30 populations. These populations are separated by inhospitable terrain, and adults rarely travel distances greater than a few hundred metres.[3]

Biotope

Nephrops norvegicus can be found at depths varying between 15 and 800 meters. Mainly on muddy or sandy-muddy bottoms, sufficiently loose so that it can dig its burrow there. These burrows are composed of tunnels buried 20-30 cm below the surface. These tunnels can reach up to 1 m in length and 10 cm in diameter for the largest. Most burrows have two openings to the surface but this number can vary (a sexually mature female will have a burrow with more openings for better oxygenation of the eggs).

Nephrops norvegicus langoustine is a sedentary crustacean, it stays most of the time hidden in its burrow. She does not come out until sunrise or sunset to go and feed because, once her eyes have been exposed to the sun, she becomes blind. However, it is possible that this habit is reversed in individuals living at greater depths, where the sun’s rays are too attenuated to be harmful.

Ecology

Nephrops norvegicus adults prefer to inhabit muddy seabed sediments, with more than 40 percent silt and clay.[3] Their burrows are semi-permanent,[7] and vary in structure and size. Typical burrows are 20 to 30 centimetres (8 to 12 in) deep, with a distance of 50 to 80 centimetres (20 to 31 in) between the front and back entrances.[3] Norway lobsters spend most of their time either lying in their burrows or by the entrance, leaving their shelters only to forage or mate.[3]

Alimentation

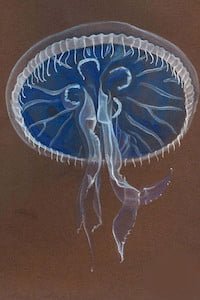

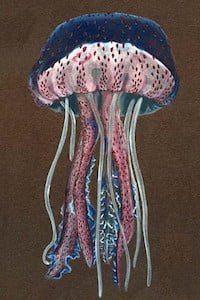

Nephrops norvegicus is a scavenger and predator[8] that makes short foraging excursions,[9][10] mainly during periods of subdued light. They feed on active prey, including worms and fish,[11] which they capture with their chelipeds and walking legs, and food is conveyed to the mouth using the anterior walking legs, assisted by the maxillipeds.[3] Although a crustacean diet provides less energy than other animals, it is rich in minerals essential for rebuilding the exoskeleton after each moult. There are, however, differences in diet that seem to be more related to the abundance of prey than to a preference for some of these prey. Nephrops norvegicus is therefore qualified as an opportunistic predator. There is evidence that Nephrops norvegicus is a major eater of jellyfish.[12]

Reproduction

The sexual maturity of langoustine is established around the age of 4 years for males and 3 years for females.

Mating takes place directly after the molt * of the female which takes place at the end of spring in the Atlantic and during winter in the Mediterranean. While the shell of the female is still soft, the two individuals side by side and the male, whose shell is still hard, introduces his sperm in the form of a spermatophore * into the genital opening of the female to the help of the pleopod * 1 which is changed into a sexual organ. The sperm can be stored for several months in the female’s spermathèque * (located between periopods 3 and 4), the spermatophore * is therefore eliminated with the exuvia * during molting.

Fertilization takes place during the emission of a few thousand eggs which are immediately attached to the pleopods of the female (the appendages under the abdomen). They will stay fixed there for a period of 8-9 months depending on the water temperature, during which the females will very little leave the burrow. To guarantee a good oxygenation quality of the eggs, their burrows have a greater number of openings towards the outside so that the water circulates more easily. It is during this period that the nauplius * larval stage will take place within the egg. The hatching will mark the entry of the larvae into the zoe * stage which will then spend a month of life in the planktonic state * before falling back to the seabed to lead their benthic * life of langoustines.

Similar Species

Nephropsis aculeata : the Florida lobster lives, as its name suggests, only in the Gulf of Mexico. It has the ends of the legs red, which contrasts with its body paler than Nephrops norvegicus .

Metanephrops binghami : the langoustine of the Caribbean, in relation to its place of life, has thinner and more elongated claws than our European langoustine.

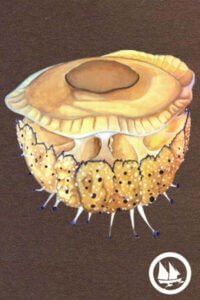

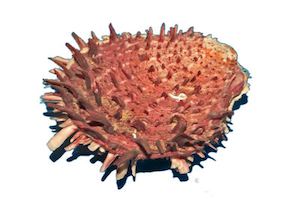

Palinurus elephas : the pink lobster, 30 to 50 cm, very long antennae, carapace bulging laterally and covered with pointed tubercles, red to brown-purple color, more or less dark, with lighter mottles, fifth pair of locomotor legs much more shorter than the others.

Munida rugosa : the pink galathea, with large slender claws, legs covered with bristles and thorns, head with two eyes protected by the carapace and surmounted by a rostrum with a supra-orbital thorn on each side. Body six centimeters maximum.

Homarus gammarus : European lobster (called in France, Breton lobster), blue in color, with smooth rostrum and medium size (60 cm without legs, weight 9 kg).

It is also possible to confuse langoustine with species of the genus Axius (including Axius stirynchus ) or Upogebia (including Upogebia pusilla or Upogebia deltaura ). Even if they look like “small langoustines”, the length of their claws is always less than that of their body.

Associated Life

Langoustine can live in association in two ways.

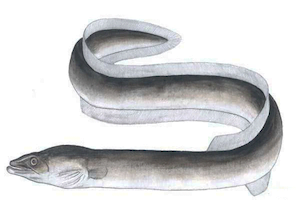

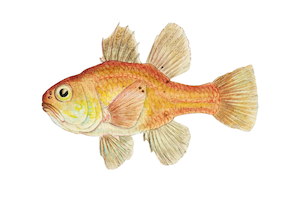

– The first association is a possible sharing of its burrow with other organisms, either with a small fish, the large-scale goby Lesuerigobius friesii , or with Gonneplax rhomboïdes a small seabed crab.

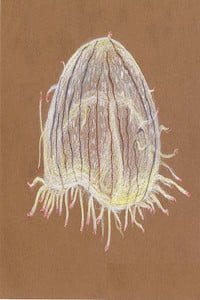

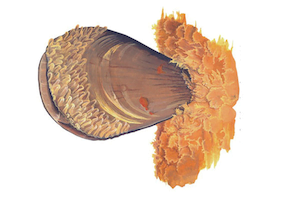

– The second possible association is much more specific. This is the association with Symbion pandora , an organism of a few tenths of a mm which can only develop on the mouthparts of Nephrops norvegicus. He spends his life fixed on them by a basal disc. It feeds on the microparticles suspended during the lobster’s diet. Its complex life cycle gives it its Latin name pandora which means “endowed with all gifts”. Indeed, its life cycle presents an alternation of mobile phases and fixed phases. This allows it to leave the exuvia (old shell) during the moult to go and attach itself to the new shell.

Parasites and symbionts

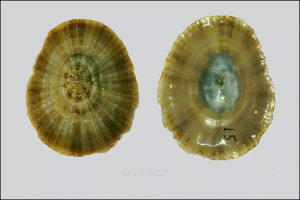

Nephrops norvegicus is the host to a number of parasites and symbionts. A number of sessile organisms attach to the exoskeleton of N. norvegicus, including the barnacle Balanus crenatus and the foraminiferan Cyclogyra, but overall Nephrops suffers fewer infestations of such epibionts than other decapod crustaceans do.[14] In December 1995, the commensal Symbion pandora was discovered attached to the mouthparts of Nephrops norvegicus, and was found to be the first member of a new phylum, Cycliophora,[15] a finding described by Simon Conway Morris as “the zoological highlight of the decade”.[16] S. pandora has been found in many populations of N. norvegicus, both in the north Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.[17] Individuals may be found on most segments of the lobster’s mouthparts, but are generally concentrated on the central parts of the larger mouthparts, from the mandible to the third maxilliped.[18]

The most significant parasite of N. norvegicus is a dinoflagellate of the genus Hematodinium, which has caused epidemic infection in fished populations of N. norvegicus since the 1980s.[14] Hematodinium is a genus that contains major pathogens of a wide variety of decapod crustaceans, although its internal taxonomy is poorly resolved.[14] The species which attacks N. norvegicus causes a syndrome originally described as “post-moult syndrome”, in which the carapace turns opaque and becomes highly pigmented, the haemolymph becomes milky white, and the animal appears moribund.[14] Other parasites of N. norvegicus include the gregarine protozoan Porospora nephropis, the trematode Stichocotyle nephropis and the polychaete Histriobdella homari.[14]

Life cycle

The typical life span of N. norvegicus is 5–10 years,[19] reaching 15 years in exceptional cases.[20] Its reproductive cycle varies depending on geographical position: “the periods of hatching and spawning, and the length of the incubation period, vary with latitude and the breeding cycle changes from annual to biennial as one moves from south to north”.[3] Incubation of eggs is temperature-dependent, and in colder climates, the duration of the incubation period increases. This means that, by the time hatching occurs, it may be too late for the females to take part in that year’s breeding cycle. In warmer climates, the combined effects of recovery from moulting and ovary maturation mean that spawning can become delayed. This, in turn, has the effect of the female missing out a year of egg carrying.[21]

Adult male Nephrops norvegicus moult once or twice a year (usually in late winter or spring) and adult females moult up to once a year (in late winter or spring, after hatching of the eggs).[3] In annual breeding cycles, mating takes place in the spring or winter, when the females are in the soft, post-moult state.[22] The ovaries mature throughout the spring and summer months, and egg-laying takes place in late summer or early autumn. After spawning, the berried (egg-carrying) females return to their burrows and remain there until the end of the incubation period. Hatching takes place in late winter or early spring. Soon after hatching, the females moult and mate again.[3]

During the planktonic larval stage (typically 1 to 2 months in duration) the nephrops larvae exhibit a diel vertical migration behaviour as they are dispersed by the local currents. This complex biophysical interaction determines the fate of the larvae; the overlap between advective pathway destination and spatial distributions of suitable benthic habitats must be favourable in order for the larvae to settle and reach maturity.[23]

Fisheries

The muscular tail of Nephrops norvegicus is frequently eaten, and its meat is known as scampi. The N. norvegicus is eaten only on special occasions in Spain and Portugal, where it is less expensive than the common lobster, Homarus gammarus.[24] N. norvegicus is an important species for fisheries, being caught mostly by trawling. Around 60,000 tonnes are caught annually, half of it in the United Kingdom‘s waters.[25]

Besides the established trawling fleets, a significant number of fleets using lobster creels have developed. The better size and condition of lobsters caught by this method yield prices three to four times higher than animals netted by trawling. Creel fishing was found to have a reduced impact on the seafloor, require lower fuel consumption, and allow fishermen with smaller boats to participate in this high-value fishery. It has therefore been described as a reasonable alternative to demersal towed gears, and the allocation of additional fishing rights for this type of take has been suggested.[26]

The North East Atlantic individual biological stocks of Nephrops are identified as functional units. A number of functional units make up the sea areas over which a total allowable catch (TAC) is set annually by the EU Council of Ministers. For example, the TAC set for North Sea Nephrops is based on the aggregate total tonnage of removals recommended by science for nine separate functional unit areas. This method has attracted criticism because it can promote the overexploitation of a specific functional unit even though the overall TAC is under-fished. In 2016, the UK implemented a package of emergency technical measures with the cooperation of the fishing industry aimed at reducing fishing activity to induce recovery of the Nephrops stock in the Farn(e) Deeps off North East England which was close to collapse. A stock assessment completed in 2018 by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) shows that fishing pressure has been cut and this stock is now below FMSY and that stock size is above MSY Btrigger meaning that the Farne Deeps nephrops stock is being fished at a sustainable level. However, ICES also warn that any substantial transfer of the current surplus fishing opportunities from other functional units to the Farne Deeps would rapidly lead to overexploitation. This suggests that controls on fishing effort should continue at least until the biomass reaches a size that is sustainable when measured against the level of fishing activity by all fishermen wanting to target the stock. [27]

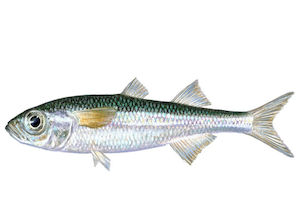

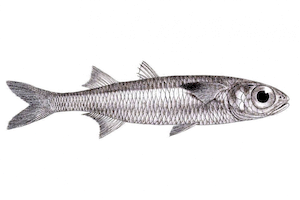

Discards from Nephrops fishery may account for up to 37% of the energy requirements of certain marine scavengers, such as the hagfish Myxine glutinosa.[28] Boats involved in Nephrops fishery also catch a number of fish species such as plaice and sole, and it is thought that without that revenue, Nephrops fishery would be economically unviable.[29]

Taxonomic history

Nephrops norvegicus was one of the species included by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae, the starting point for zoological nomenclature. In that work, it was listed as Cancer Norvegicus, with a type locality of in Mari Norvegico (“in the Norwegian sea”).[30] In choosing a lectotype, Lipke Holthuis restricted the type locality to the Kattegat at the Kullen Peninsula in southern Sweden (56°18′N 12°28′E).[2] Two synonyms of the species have been published[2] – “Astacus rugosus“, described by the eccentric zoologist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1814 from material collected in the Mediterranean Sea,[31] and “Nephropsis cornubiensis“, described by Charles Spence Bate and Joshua Brooking Rowe in 1880.[32]

As new genera were erected, the species was moved, reaching its current position in 1814, when William Elford Leach erected the genus Nephrops to hold this species alone.[2][33] Seven fossil species have since been described in the genus.[34]

Populations in the Mediterranean Sea are sometimes separated as “Nephrops norvegicus var. meridionalis Zariquiey, 1935″, although this taxon is not universally considered valid.[3]

North American transplant

The Norway lobster has reportedly been transplanted and released in North America by Erik Jensen. Jensen procured 300-500 fertilized eggs and proceeded to introduce Puget Sound salt water each time a batch molted from the larvae stage. After two months in a salt tank, the Norway lobsters were released into Filucy Bay in Puget Sound near Longbranch, Washington.[35]. The ethics and legality of this has been controversial.