Homarus Gammarus

– European Lobster –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] |

| Scientific classification |

Homarus gammarus (Linnaeus, 1758)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Family: | Nephropidae |

| Genus: | Homarus |

| Species: | H. gammarus |

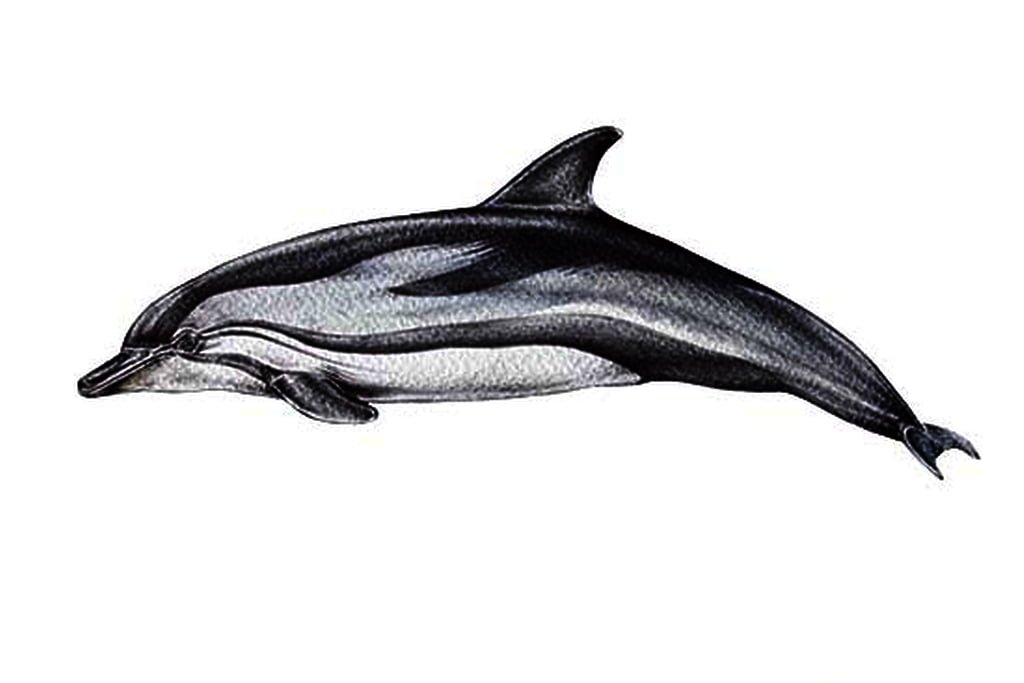

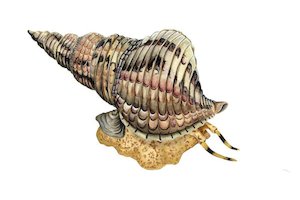

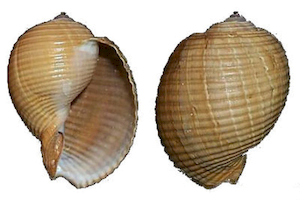

Homarus gammarus, known as the European lobster or common lobster, is a species of clawed lobster from the eastern Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea and parts of the Black Sea. It is closely related to the American lobster, H. americanus. It may grow to a length of 60 cm (24 in) and a mass of 6 kilograms (13 lb), and bears a conspicuous pair of claws. In life the lobsters are blue, only becoming “lobster red” on cooking. Mating occurs in the summer, producing eggs which are carried by the females for up to a year before hatching into planktonic larvae. Homarus gammarus is a highly esteemed food, and is widely caught using lobster pots, mostly around the British Isles.

Description

Homarus gammarus is a large crustacean, with a body length up to 60 centimetres (24 in) and weighing up to 5–6 kilograms (11–13 lb), although the lobsters caught in lobster pots are usually 23–38 cm (9–15 in) long and weigh 0.7–2.2 kg (1.5–4.9 lb).[3] Like other crustaceans, lobsters have a hard exoskeleton which they must shed in order to grow, in a process called ecdysis (molting).[4] This may occur several times a year for young lobsters, but decreases to once every 1–2 years for larger animals.[4]

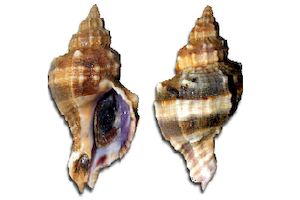

Its carapace is bluish often dark, with the tips of the legs white and the antennae orange.

Its body is made up of a cephalothorax, a long, powerful, folded-up abdomen at rest, and a tail.

Two large claws are located at the front of the cephalothorax, unlike the lobster, which does not have one. Its 2 clamps are different : the larger one, armed with irregular teeth, crushes, while the other, thinner and armed with a row of saw teeth, cuts. They are located either right or left and are particularly powerful (see additional information).

Its eyes are located on mobile peduncles *, allowing a very wide 180 ° vision.

The lobster has two pairs of antennae : the antennae for the “smell”, the large antennae for touching it (detection of a possible danger). Moreover, while diving, you will be able to observe the lobster touching its environment, even the diver (subject to calm and patience). Its oral appendages are the mandibles *, maxillae and maxillae, used for chewing and for the circulation of water in the gills. It has a rostrum * at the front of the head, this one is provided with spines all turned upwards.

Finally, its tail ends in a suchon *, forming a powerful caudal fin.

Differences are visible between the male and the female. The male has large pincers and a slender body while the female has smaller pincers and a wider abdomen.

The first pair of pereiopods is armed with a large, asymmetrical pair of feet.[2] The larger one is the “crusher”, and has rounded nodules used for crushing prey; the other is the “cutter”, which has sharp inner edges, and is used for holding or tearing the prey.[4] Usually, the left claw is the crusher, and the right is the cutter.[5]

The exoskeleton is generally blue above, with spots that coalesce, and yellow below.[6] The red colour associated with lobsters only appears after cooking.[7] This occurs because, in life, the red pigment astaxanthin is bound to a protein complex, but the complex is broken up by the heat of cooking, releasing the red pigment.[8]

The closest relative of H. gammarus is the American lobster, Homarus americanus. The two species are very similar, and can be crossed artificially, although hybrids are unlikely to occur in the wild since their ranges do not overlap.[9] The two species can be distinguished by a number of characteristics:[4]

- The rostrum of H. americanus bears one or more spines on the underside, which are lacking in H. gammarus.

- The spines on the claws of H. americanus are red or red-tipped, while those of H. gammarus are white or white-tipped.

- The underside of the claw of H. americanus is orange or red, while that of H. gammarus is creamy white or very pale red.

Life cycle

Female H. gammarus reach sexual maturity when they have grown to a carapace length of 80–85 millimetres (3.1–3.3 in), whereas males mature at a slightly smaller size.[4]Mating typically occurs in summer between a recently moulted female, whose shell is therefore soft, and a hard-shelled male.[4] The female carries the eggs for up to 12 months, depending on the temperature, attached to her pleopods.[4] Females carrying eggs are said to be “berried” and can be found throughout the year.[2]

The eggs hatch at night, and the larvae swim to the water surface where they drift with the ocean currents, preying on zooplankton.[4] This stage involves three moults and lasts for 15–35 days. After the third moult, the juvenile takes on a form closer to the adult, and adopts a benthic lifestyle.[4] The juveniles are rarely seen in the wild, and are poorly known, although they are known to be capable of digging extensive burrows.[4] It is estimated that only 1 larva in every 20,000 survives to the benthic phase.[10] When they reach a carapace length of 15 mm (0.59 in), the juveniles leave their burrows and start their adult lives.[10]

Distribution

Biotope

It is found on rocky bottoms up to a hundred meters deep. It has become rare to fish for low water; the Chausey archipelago is one of the places where it is still possible at very good tides.

By day, he lives hidden in his shelter, often in faults, holes or wrecks, which he constantly rearranges by pushing the sediment outwards with his pincers. At night, it can be seen roaming the rocks in search of its food. It is a fairly aggressive animal, which attacks any animal smaller than its own. This aggressiveness is also manifested towards its congeners, especially by large males for the defense of shelters, territories, battles for females.

Homarus gammarus is found across the north-eastern Atlantic Ocean from northern Norway to the Azores and Morocco, not including the Baltic Sea. It is also present in most of the Mediterranean Sea, only missing from the section east of Crete, and along only the north-west coast of the Black Sea.[2] The northernmost populations are found in the Norwegian fjords Tysfjorden and Nordfolda, inside the Arctic Circle.[11]

The species can be divided into four genetically distinct populations, one widespread population, and three which have diverged due to small effective population sizes, possibly due to adaptation to the local environment.[12] The first of these is the population of lobsters from northern Norway, which have been referred to as the “midnight-sun lobster”.[11] The populations in the Mediterranean Sea are distinct from those in the Atlantic Ocean. The last distinct population is found in the Netherlands: samples from the Oosterschelde were distinct from those collected in the North Sea or English Channel.[12][13]

Attempts have been made to introduce H. gammarus to New Zealand, alongside other European species such as the edible crab, Cancer pagurus. Between 1904 and 1914, one million lobster larvae were released from hatcheries in Dunedin, but the species did not become established there.[14]

Ecology

Adult H. gammarus live on the continental shelf at depths of 0–150 metres (0–492 ft), although not normally deeper than 50 m (160 ft).[2] They prefer hard substrates, such as rocks or hard mud, and live in holes or crevices, emerging at night to feed.[2]

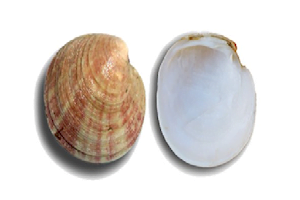

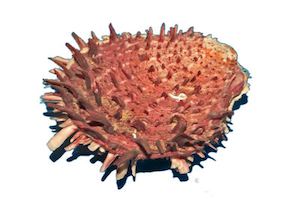

The diet of H. gammarus mostly consists of other benthic invertebrates. These include crabs, molluscs, sea urchins, starfish and polychaete worms.[10]

The three clawed lobster species Homarus gammarus, H. americanus and Nephrops norvegicus are hosts to the three known species of the animal phylum Cycliophora; the species on H. gammarus has not been described.[15]

Homarus gammarus is susceptible to the disease gaffkaemia, caused by the bacterium Aerococcus viridans.[4] Although it is frequently found in American lobsters, the disease has only been seen in captive H. gammarus, where prior occupation of the tanks by H. americanus could not be ruled out.[4]

Alimentation

It is a carnivore, it consumes any animal it can control or catch. Its prey is rather slow-moving animals, such as mollusks, worms and echinoderms, but occasionally it can be crustaceans and fish, dead animals and algae. After molting, it has been observed consuming its shell, possibly to “recover” the calcium useful for hardening its new shell.

Its predators are octopus and humans. For human interaction, see the chapter “Further information”.

Reproduction

A solitary animal, the lobster accepts the presence of its congeners only during reproduction.

The sexes are separated and mating takes place after the female molts, when the cuticle * of the latter is still soft. Mating is often preceded by foreplay and courtship displays. Thanks to his abdominal appendages modified into a copulatory organ, the male introduces his sperm into the seminal receptacle of the female, which is stored in a pouch (spermatheca *).

The female can fertilize her eggs with the same sperm for at least two successive years. The larger the female, the more eggs she produces, around 5,000 to 50,000. They are laid between July and December and are worn on the abdominal appendages (pleopods *) of females for about 7 to 10 months. 1/3 of the eggs are lost during incubation. During hatching, the female shakes her pleopods to release the eggs. Hatchings, spread over several months depending on the female, are at their maximum in May-June. It is estimated that only 2 to 3 individuals of the offspring reach adulthood.

The released larvae go through several planktonic stages * between April and August for 1 month, during which they moult 4 times before becoming post-larvae (resembling small adults) and starting a benthic life *. The temperature of the water influences the time it takes for the larvae in this pelagic process *. The colder the water, the slower the process (110 days at 10 ° C, 34 days at 18 ° C). The larvae swim to the bottom and quickly find shelter.

On average, the lobster moults 10 times the first year, 3 to 4 times the second, 1 to 2 times the third, once only then, and then less and less frequently until the growth stops completely.

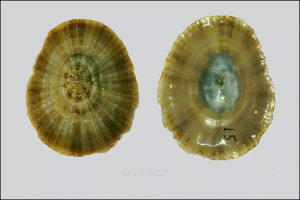

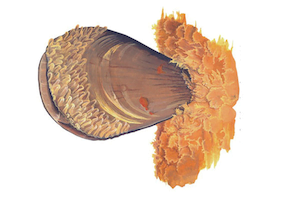

Associated Life

According to Ifremer, lobster is parasitized by protozoa, such as the sporozoan of the genus Aggregata and the gregarin Porospora gigantea , by the copepod Nicothoe astaci (crustaceans) and the annelids Histriobdella homari (worms). The latter is found in the branchial cavity or in the eggs. An amphipod Isaea elmhirsti (crustacean) seems to live permanently between the mouthparts of the lobster, without parasitizing it.

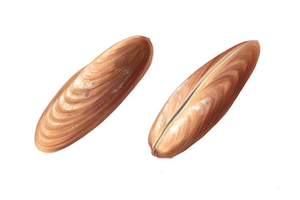

Although much less covered than the shells of spider crabs or those of Inachus crabs , lobster shells can be covered with certain invertebrates (epibiosis * by polychaete annelids, or bryozoa …).

Although it is less common than it has sometimes been reported, the association of conger eel and lobster is very real… (see photo).

It has been claimed that the conger eel was waiting for its roommate to moult before putting it on his menu, this remains to be proven!

What is the exact nature of this curious association, that’s a good question …

Various Biology

Son observation est particulièrement intéressante de nuit, car il sort de son abri pour chasser. C’est là l’occasion de le voir en entier !

Son espérance de vie atteint 15 à 20 ans, mais la pêche intensive la réduit considérablement. En aquarium, des spécimens ont été conservés pendant une cinquantaine d’années. Certains ont avancé un âge de 100 ans, sans certitude, pour les plus gros individus connus.

C’est un crustacé, ce qui signifie qu’il a une carapace non extensible. Pour grandir, il doit donc muer. Le homard mue quasiment toute sa vie, avec un ralentissement avec l’âge. La taille du homard croît d’environ 20 % à chaque mue. Celle-ci se fait plutôt au printemps et en été selon les conditions climatiques.

Its shell is blue when alive but turns red when cooked. The responsible molecule is astaxanthin coupled with proteins to form a complex pigment called crustacyanin. This molecular complex shifts the absorption wavelength of light (it goes from 472 nm without crustacyanine to 632 nm with). Cooking, by coagulating the crustacyanin protein, releases astaxanthin and returns it to its red color. It should be noted in passing that the coloring of the eggs is due to even more complex pigments of very high molecular weight, namely lipo-glyco-caroteno-proteins.

Common species in the Channel and the Atlantic and much less in the Mediterranean.

Similar Species

The American lobster Homarus americanus is the closest species, but it is distinguished by its dark green to brown coloring (orange on the belly), its claws are wider and flat.

Its rostrum bears a spine in a lower position, which is not the case in the European lobster.

It lives in North America and is not found on our coasts. (It was introduced in the Netherlands).

No confusion possible in France.

Human Consumption

Homarus gammarus is traditionally “highly esteemed” as a foodstuff and was mentioned in “The Crabfish” a seventeenth century English folk song.[16] It may fetch very high prices[2] and may be sold fresh, frozen, canned or powdered.[2] Both the claws and the abdomen of H. gammarus contain “excellent” white meat,[17] and most of the contents of the cephalothorax are edible. The exceptions are the gastric mill and the “sand vein” (gut).[17] The price of H. gammarus is up to three times higher than that of H. americanus, and the European species is considered to be more flavored.[18][dubious – discuss]

Lobsters are mostly fished using lobster pots, although lines baited with octopus or cuttlefish sometimes succeed in tempting them out, to allow them to be caught in a net or by hand.[2] In 2008, 4,386 t of H. gammarus were caught across Europe and North Africa, of which 3,462 t (79%) was caught in the British Isles (including the Channel Islands).[19] The minimum landing size for H. gammarus is a carapace length of 87 mm (3.4 in).[20] To protect known breeding females, lobsters caught carrying eggs are to be notched on a uropod, the inner tail flap of female lobsters of reproductive size (usually above the minimum landing size 87mm carapace length). Following this, it is illegal for the female to be kept or sold, and is commonly referred to as a “v-notch”. This notch remains for three molts of the lobster exoskeleton, providing harvest protection and continued breeding availability for 3–5 years.[21]

Aquaculture systems for H. gammarus are under development, and production rates are still very low.[12]

Taxonomic History

Homarus gammarus was first given a binomial name by Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae, published in 1758. That name was Cancer gammarus, since Linnaeus’ concept of the genus Cancer at that time included all large crustaceans.[22]

H. gammarus is the type species of the genus Homarus Weber, 1795, as determined by Direction 51 of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.[23] Prior to that direction, confusion arose because the species had been referred to by several different names, including Astacus marinus Fabricius, 1775 and Homarus vulgaris H. Milne-Edwards, 1837, and also because Friedrich Weber’s description of the genus had been overlooked until rediscovered by Mary J. Rathbun, rendering any prior assignments of type species (for Homarus H. Milne-Edwards, 1837) invalid for Homarus Weber, 1795.[24]

The type specimen of Homarus gammarus was a lectotype selected by Lipke Holthuis in 1974. It came from 57°53′N 11°32′E, near Marstrand, Sweden (48 kilometres or 30 miles northwest of Gothenburg), but both it and the paralectotypes have since been lost.[2]

The common name for H. gammarus preferred by the Food and Agriculture Organization is “European lobster”,[2] but the species is also widely known as the “common lobster”.[6][25

]

Further Information

Be careful, the pliers can cut a finger! So, as a good diver who respects himself, avoid touching or catching them …

Man appreciates his gastronomic qualities.

The species has become rare in many places because of its overexploitation, and in particular through trap fishing. Pollution is locally responsible for the decrease in populations.

It is more common in the Atlantic-Channel than in the Mediterranean. 2/3 of the production comes from the Channel, the rest from the Bay of Biscay. This set does not allow national consumption to be satisfied and France has to massively import lobsters from Ireland and Great Britain, but also from North America ( Homarus americanus , the American lobster).