Despite the strong garrisons that were established by the knights of St. John, the early 15th century saw a dramatic increase in Ottoman turkish raids on the eastern Aegean islands. Already by the 14th century the coast of Asia minor opposite the Dodecanese formed the ottoman principality of Mentese, and in the ongoing conflict between christian and islamic nations, armed ottoman bands often undertook random attacks as part of a sacred war, or “intifada”. In 1449 a monk called Gregorio’s reported incursions by armed bands on Nisyros and Calymnos, in which the town were burnt pillaged(205).

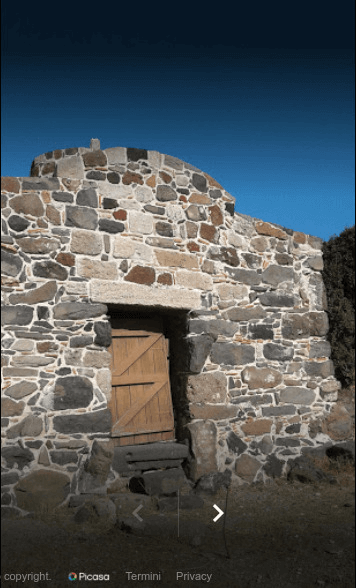

Immediately after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Nisyros was fortified by the Knights in anticipation of massive Ottoman attacks. Five castles are mentioned in a document from the library of Malta(Arch. No. 364,”Liber Bullarum 1453-54), which are the same as reported by the florentine monk Buondelmonti: Mandraki, Palaiokastro, Pandoniki(Emporios), Nikia and Argos(206). Another document form this period records fortifications at the site of Avia, Oriyes and Perva, all which places are unknown to us.(207). It is possible that Perva is the fort at the location known as Parletia, as the Knights describe it as being in the center of the island with traces of older defensive structures.

In 1455 an Ottoman fleet led by Hamza Hey attacked Nisyros and carried off many of its inhabitants, selling them into slavery. Again in 1457 the island was overwhelmed by an ottoman fleet, this time comprising as many as sixty war vessels(208). The troops massacred those inhabitants whom they found outside the fortifications, and ravaged the countryside. Many of the survivors were evacuated to the larger island, and repatriated after the Knight’s garrison was significantly strengthened. To encourage the Greeks to remain on their native islands, the Knights abolished taxation there(209).

Twenty six years later, in 1483, Ottoman invaders returned, leaving many inhabitants dead, with scores of survivors desperately seeking refuge in Rhodes. For almost five decades after this last disaster, Nisyros remained practically deserted. The fall of Constantinople and the continuing victories of the Ottomans against the Byzantines and the Knights discouraged Nisyrians refugees from returning immediately.

In 1471, the “Grand Magistrate of Rhodes” Giovanni Battista Orsini, in whose charge Nisyros had meantime been placed, handed the island to the Catalan Knight Galcerano da Lugo, with orders to prevent the Ottomans from returning and using the island as military base. By this time, living conditions were so deplorable, with the town lying largely abandoned and dilapidated, as to cause Pietro Utino, the bishop appointed to Nisyros by the Pope in 1475, to quit the place in dismay immediately after his arrival.

Ottoman and piratatical raids continues throughout this period, despite attempts by the Knights to streghten their defenses. In 1504, the notorious turkish pirate “Kemal Reis Camale” came close to capturing the island, but encountered fierce resistance a decided to withdraw(210).

Finally, in 1522, “Suleiman the Magnificient” extracted the eastern Aegean island from the Knights under the command of their last rhodian Grand Master, Philipp Villiers de l’isle Adam. On September, 6th of this fateful year, Nisyros, seeing its unavoidable fate, willingly succumbed to Ottoman occupation.It emerged from turkish control only 1912 with the capture of the Dodecannese islands by the Italians.

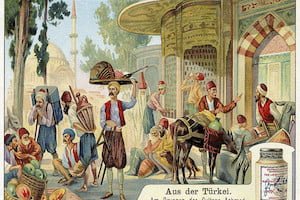

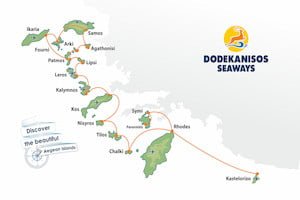

Ottoman law ensured that willful subjects could retain local autonomy in exchange for larger political allegiance and payment of taxes. Thus, the twelve islands Icaria, Patmos, Leros, Calymons, Nisyros, Astypalaia, Symi, Tilos, Halki, Cassos, Carphatos and Castellorizo, enjoyed a degree of political freedom as the Ottoman province “Isporad Adasi”, which gave rise to the greek term “Dodecanese” (twelve islands).

Cos and Rodhes were not part of the province, and had no autonomy because they resisted the turkish invasion. However, despite Suleiman and the subsequent sultans’ decrees (firmans) guaranteeing privileged status to the Dodecanese, turkish rule was from beginning severe and structured to gradually eradicate the local religion and national sentiment. Substantial privileges were bestowed on natives who would convert to Islam and more generally adopt the turkish language and customs.

A head tax(the maxtou) was imposed on christian subjects, which was used to finance and support islamic institutions in Cos and Rhodes. The eldest ablebodied sons were often required to join the “Janissary corps”, an elite and muchfeared body of islamized native troops.Those islamized men who reembraced their families’ christian faith were typically put to death, often by dismemberment or beheading.

One 15 years old Nisyrian by the name Nikitas Karmiris, later canonized as “Agios Nikita” by the greek orthodox church, is known to have suffered just such a fate in 1574(211).As the story has it, Nikitas’ father Nikolai’s Karmiris, a wealthy landowner who was serving as mayor(“protogeros”) of Mandraki, was arrested as the representative of the islanders on various charges leveled against them by the Ottoman authorities, and imprisoned in the infamous jails of Halicarnassus (Bodrum).

From there he was taken to Rhodes to be tried; fearing for his life, and having suffered unspeakable tortured aimed to extracting more and more ransom money to his family on Nisyros, Nikolaos converted to Islam. The same was consequently required of his children, including Nikita’s who was an infant at the time. Despite his conversion, Nikolaos was put by dismemberment, his wife was carried of to the rhodian Pasha’s harem after this official took a fancy to her.

Years later Nikitas , who had grown up believing he was the Pasha’s son, was told by his mother of his Nisyrian origins, and the fate of his real father.

This caused him to renounce the islamic faith that had been forced upon him and to embrace christianity. Eventually he was arrested, and after refusing to return to islam, beheaded. His younger brother Ioannis was so moved by his brother’s death in Christ as to declare himself in turn a “Greek and Christian”, and sought the punishment of his father’s accusers and murderers.

Perhaps because they were afraid to ignite a local greek insurrection, the ottoman authorities in Rhodes refrained from arresting him; he eventually returned to Nisyros, where he served as priest until his death 1536.

Despite the severity of Ottoman rule, the establishment by “Suleiman the Magnificent” of order through overwhelming military superiority eased the fear of piracy and the continual military skirmishes that had kept Nisyrians in a constant and exhaustive state of vigil. Nisyrian refugees gradually made their way back from Rhodes after 1522.

Their return was encouraged by Suleiman, who also recognized that the islanders would keep to check piracy in the area, if permitted to act with a degree of independence; thus, incentives for the inhabitants to remain subjects of the Ottoman empire were maintained (212). The islanders were free to organize themselves into local councils, which they called “dimogeronties).

The dimogeronties(community elders) were elected yearly by popular vote, elections being held usually in a churchyard. These local governments, which were later called “dimarchies”, curiously echoed the system of government in classical and hellenistic times. On every island a Turkish clerk(” moudiris, soumbasis or kaïmakamis) was installed and played by the dimogerontia.

On Nisyros this official and his family, few gendarmes (zaftiedes) and customs officials are the only turks known to have been present during centuries of Ottoman occupation.One retired turkish clerk , known as Ali, was so well liked by the Nisyrians , that they convinced the italian troops who ‘liberated the island from turkish rule in 1912,, to allow him to remain there. Typically, there were two or three dimogeronties, one acting as president(proedros) and others as member(paredroi). Along with every newly elected dimogerontia a managing council was also elected.

It is interesting to note that the dimogerontia, which had governmental as well as policing powers, was maintained by the Italians after their occupation of the Dodecanese in the first half of the 20th century.(213) The men who served in the dimogeronties were instrumental in maintaining the privileges that were originally bestowed on the islands by Suleiman; the continuing greekness of local government was one of the reasons for which turkish settlers never established themselves on Nisyros and the rest of the Dodecanese, with exception of the politically separate and more strategic Rhodes and Cos.

In the second half of the 18th century, Nisyros and other islands of the greek archipelago experienced a relaxation of Ottoman authority due to the outbreak of Russo-Turkish war(1769-1792). This war was the result of an ambitious plan by Empress Catherina of Russia to liberate Greek orthodox population from ottoman rule, and was begun with the destruction of the ottoman Aegean fleet off the island of Chios.Eventually a conditional peace was signed, in which Russia agreed to withdraw from the Aegean, while maintaining the right to come to the rescue of Christians in the event of mistreatment by the Ottomans.

The apparence of the Russian fleet, supported by Greek independence fighters like “Lambros Katsonis”(214), had the additional advantage of checking piracy in the Aegean. This newfound security, combined with the establishment of prosperous Nisyrian colonies in Odessa, Constantinople and Izmir, prompted the islanders to treat their churches more sumptuously: icons were gilded, elaborate chancel screens were built, and ambitious buildings programs were undertaken again.