Philip’s son Alexander the Great claimed Nisyros and the surrounding islands in 334 BC, shortly after invading Persian-held Asia Minor. Macedonian rule was at first tolerated and then welcomed as a necessary imposition of order in the area by a Hellenic power. After death of Alexander his empire was divided into smaller states that were governed by his generals.

The conflicting interests of these dinasts threw the greek world into turmoil, armies and fleet clashing frequently in the struggle for political control.

In the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, Rhodes began to incorporate many of the smaller islands in the region into its territories, including Caria and Lycia on the coast of Asia Minor. It is likely that Nisyros joined what came to be known as the Rhodian Peraea around 200 BC. By the beginning of the 2nd century BC the various hellenistic kingdoms and city states had been exhausted by constant warfare; Rhodes itself became the first greek state to court Rome, in an effort to shake off designs by king Philipp V the Macedon.

This last ruler (221-179BC) had set up an alliance with the carthaginian general Hannibal, them joined king Anthiocos III of Syria angainstbthe child-king Ptolemy Epiphanes of Egypt. Philip’s plan were resisted by the rhodian and the neighboring islands of Cos, Nisyros, Calymnos and Carpathia, as well as the city of Pergamon, which were allied to the Ptolemies. Together, the island forces resolved to block the passage of Philip’s ships on their way from the northern coast of Asia minor to Egypt. In response, Philip moved against the Rhodians and their allies, who now included a volunteer force sent by Rome, and embarked on what came tonne known as the Cretan War.

To subdue the Rhodians, Philip persuaded the island of Crete, which was known to waver politically according to its foreign interests, to wage war against the Rhodians. Philip dispatched a notorious pirate by the name of Dikaiarchos, an Aetolian based in the Cycladic islands, to act as advisor to the Cretans. Soon afterwards the Hhieraptian Cretans launched an attack against Cos, which was defended by admiral Lysandros, the son of Phoenix.

At the naval battle off the Clan peninsula of Laceter(near the actual town of Kardamena opposite Nisyros), Lysander managed to rout the Cretans. An inscription has been found in Mandraki apparently honoring the victories of Nisyrian admiral Gnomagoras(who fought in the Cretan War under the rhodian admiral Astymedes), or according to a recent study, Gnomagoras’ compatriot, Aristocrates.

In the meantime Philip’s fleet was preparing to descend the coast of Asia minor. Together with the Pergamenes, the Rhodians sailed north to Chios to meet the Macedonians. There, in 201 BC, after a furious naval battle, Philip was defeated. Shortly after the Rhodians had begun heading south again, however, he managed to regroup and capture the island of Samos, which, together with Leros, Leipsoi, Patmos, and short time later Cos and Calymnos, joined him in his campaign.

His next move was to capture Caria on the coast opposite Nisyros, to which he then naturally turned his attentions. An inscription found near the church of Panagia Potamitissa in Mandraki records the message sent by Philip to the Nisyrians, by the way of his Nisyrian agent Callias, in which he sought their favor and urged them to abandon Rhodian alliance. Around this time, admiral Gnomagoras appears to have commanded a ship of the sort known as a “Triemolia” . In compensation for his victories, he was crowned with golden wreaths.

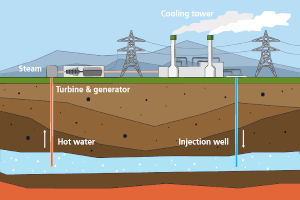

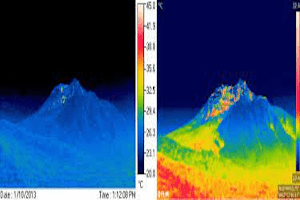

In the 1st century AD, geographer Strabo’s tells us that Nisyros had one city, a harbour, thermal baths, and a temple of Poseidon. The city was no doubt located in the area of the modern town of Mandraki at the northwest corner of the island, where the ruinsof the ancient acropolis occupy a promontory(known as ‘O oxos the Panagias’) that thrusts northward into the sea.

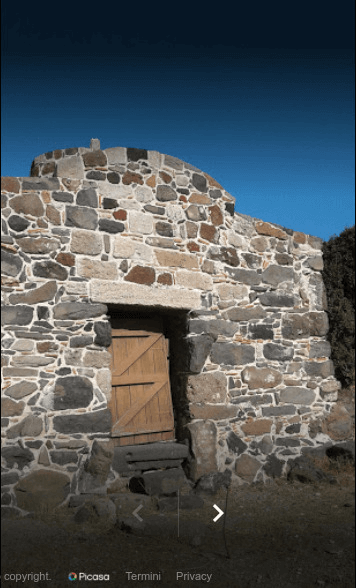

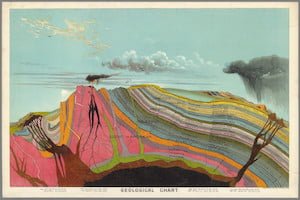

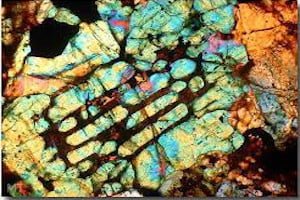

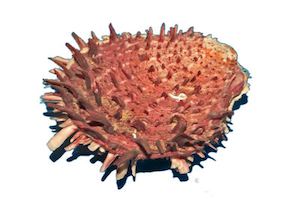

The acropolis fortifications consists of two long, perpendicular, mostly isodomic walls of black trachite running due west and north respectively, varying from three to four meters in width with square projecting towers about 10mr wide each, and about twenty five meters apart. As mentioned previously in connection with the remains from prehistoric times, it appears that the northernmost parts of the north-south running wall are Mycenaean date; the carefully-built isodomic walls probably date from the 4th century BC. Together, the fortifications enclose an area that slopes down toward the cliff edge overlooking the pebble beach of Choclakoi to the north.

The principal gate into the acropolis is located just to the north of the south east corner tower, facing south. Two large stone staircases survive near the gate, the one to the north and the other to the west on the east-west wall.

On the first tower to the north of the gate there is an official inscription:

‘ΔΑΜΟΣΙΟΠΤΟ ΧΩΡΙΟΠΠΕÎΤΕ ΠΟΔΕΣ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΤΕΙΧΕ(ΟΣ)’

declaring that a strip of land five greek feet(about 1,50mt 1gr ft= 30,8 cm) in width along the walls must remain property of the state,’damos’. Similar inscriptions are known from Ephesos and Paris, and were intended to prevent erection by citizens of buildings that might facilitate enemy scaling of the walls.

The north-running fortification wall drops downward along the natural gully of Potamos in Mandraki, where it appears to be intersected perpendicularly by an other, east running wall. This last structure seems to have enclosed a large unbuilt area, possibly the ancient city’s harbor mentioned by Strabo. The archaeologist Ludwig Ross, in the 19th century, informs us that only 30 years before his visit in Nisyros, in 1841, the site was a marshy area known as Lines by the natives; the name is possibly a contraction of the ancient greek word ‘limenes’, the plural for harbor, or a reference to the ponds(‘limnes’) of more recent times.

Immediately to the east of Limnes, in the district of Mandraki knows as Agio Savvas, there are a series of massive ancient terrace walls, also of black trachite; these walls, the different masonry styles of which indicate that they were constructed at different times, are likely to be the remains of the fortifications that enclosed the harbor, or large civic or religious buildings perhaps associated with an ancient cemetery that has been discovered here.

Another cemetery with extensive Archaic and Roman burials was also discovered to the south of Mandraki, near the chapel of Agio Iohannis.

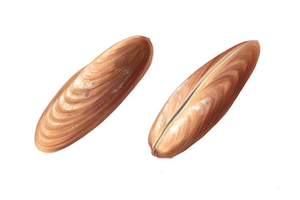

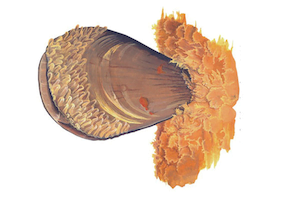

To the east of Mandraki, about halfway to the municipal baths along the coastal road, at the site called ‘Mylocratis’ , are said to be remains of ancient quarries from which Nisyrians extracted volcanic stone to fashion their famous millstones that were exported throughout the greek world.

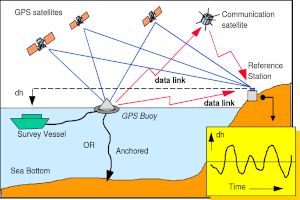

The walls at Palaiokastro formed part of a higly organized defensive system that included watchtowers and lighthouses around the island and on the nearby islets. Two towers from the Greco-Roman period have been found on the islet of Pyrgoussa, and other have been identified on the south west side of Nisyros by Lazaros Kontoveros in 1959, at Dracospilio on Cape Lefkos, and at Pyrgoi near Kateros; and one in Skopi near the municipal baths.

It is possible that the ruins at ‘Ta Ellenika’ at Argos, and ‘Ta Ellenika’ at Avlaki, mentioned elsewhere on this site, also included watchtowers. The guards of these towers were called the ‘phryktoroi’ or ‘signalgivers’, and their job was to transmit information about approaching ships and other naval activity in the area around Nisyros.

The reference in the 2nd century BC, Nisyrian inscription to the temple of Argive Poseidon and the existence of a region known by local as ‘Argos’ in the southwest of Nisyros have caused to speculate that a second Greek city called Argos existed. The site of Ta Ellenika, Kallipolis, Palisia and the monastery of Stavros in the region of Argos have all been put forward as likely locations for the presumed city.

With the exception of ‘Ta Ellenika’ and, possibly, Stavros, these places are not known to have remains of ancient habitation. It is also unclear if the ‘Argeios’ mentioned in the inscriptions is in fact a place name or an epithet of Poseidon.

However the region of Argos(a name believed by some to have originally meant a fertile plain) may have been overlooked by a coastal temple of the sea god, possibly the same one cited by Strabo. The remains of a large isodomic structure of black trachite at the place called ‘Ta ellenika’ at Argos belong perhaps to this temple.

From an inscription found in the ruins of the roman baths at the modern town of Paloi, it is clear that this site was occupied by an earlier greek bathing establishment, and very likely a small settlement. Certanly the natural harbor there was a good one, and not too distant from the principal city; it would likely have been put into use in ancient times when the main port in the city of Nisyros was crowded with ships. Nisyros was renowned in classical times for its thermal waters; the father of ancient medicine Hippocrates, whose birthplace was the city of Astypalaia on the Cephalos peninsula of Cos closest to Nisyros, would himself no doubt have been familiar with their therapeutic qualities.

The site of Armas, Nikia, Emporios, and Chorio on the road from Nokia to the little anchorage of Avlaki on the southeast coast of the island, have been suggested as possible location for smaller settlements in the classical period, but these are not known to have revealed any traces of ancient habitations. It is, however, as Ellinika to the east of Avlaki, where ruins of large isodomic buildings of black trachite and a curious tumulus-like mound are visible.

Three tower structures are reported near the place called Kateros or Katergos(labor camp) and one at Dracospilio near Argos. It is believed that there were Nisyrian colonies on the island of Saros and Calymnos, and Nisyrian neighborhoods are known to existed on Cos(nisyriades) and Rhodes.

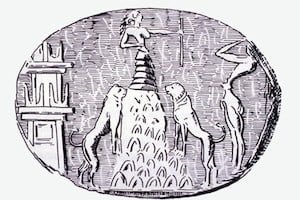

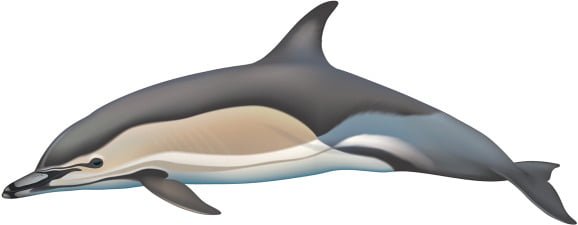

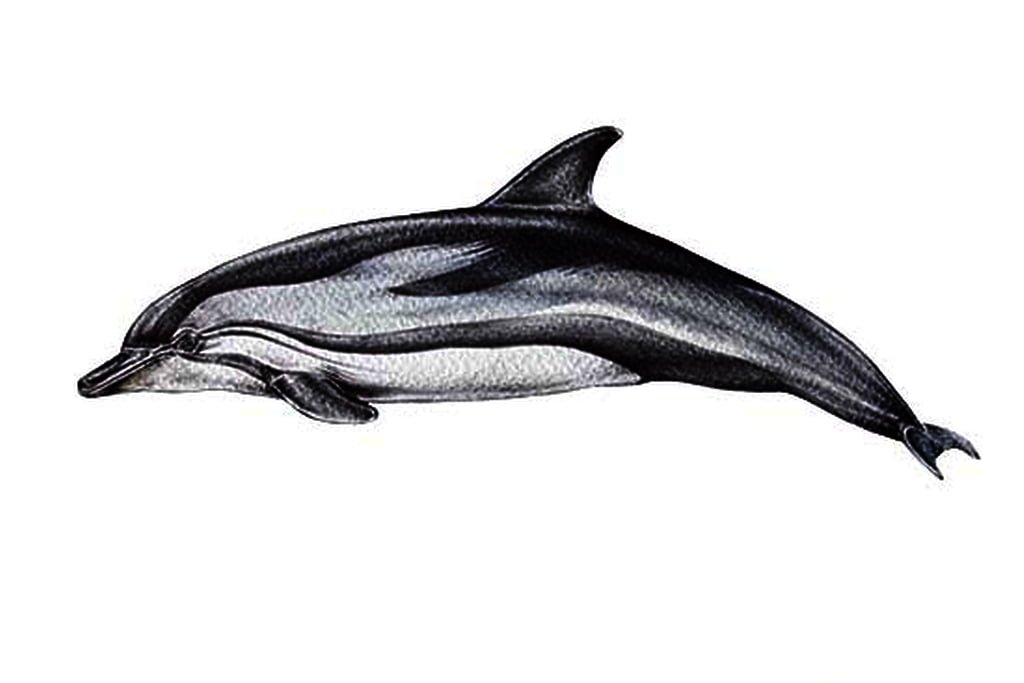

Strabo tells us that the island’s principal deity was Poseidon. The importance of his cult is confirmed by ancient Nisyrian coins on which this god is represented either as a bearden head, or sitting on a rock with his trident in hand, or symbolically in the form of entwined dolphin and trident. Cults of other Nisyrian deities, to whom shrines and temples are either known of likely to have existed, included Zeus Meilichios(a subterranean cult of a mild fatherly god), Hera, Ares, Aphrodite, Artemis, Hermes, Dionysios, Tyche, and the hypochthonic deities Lethe and the Moirae(fates).

The cult of Apollo, the national god of the Dorian’s, was particularly prominent. He was worshipped under the epithets Delios, Carneios, and Delphinios or Delphidios. Elements of pre-hellenic religion appear to have survived into classical times in cults like those of Apollo Smyntheus, and Apollo Nisyreites.

It have been argued that the terrace walls of black trachite that a e visible in the district of Agios Savvas in Mandraki belong to the temple of Poseidon mentioned by Strabo. This view, however, is based entirely on the monumental appearance of these walls, and a possible survival of ancient worship of Poseidon at the church of Agios Nikolaus(patron saint of mariners) which sits in the modern cemetery adjacent to the ancient building.

The remains of a large well built classical building, almost certainly a temple, occupy the highest point inside the medieval castle near the pilmigrage church of Panagia Spiliani. These foundations are made of large trachite ashlar blocks like the 4th century walls at Palaiokastro. In its day the building would have commanded the entire lower town and harbor, beckoning ships approaching from the west around the promontory.

A few of other temple ruins in and about the city of Nisyros have been located, and in some cases identified. One temple, possibly belonging to Hermes, sits just outside the gate and to the southwest of the ancient acropolis; another can be seen near the area of Jambi about ten minutes walk south of the acropolis on the road to Argos. Fragments of a marble Doric entablature (“thringos”), complete with its projecting mutules (“promochthoi”) and guttae (“stalagma”), in the ruins of an early christian basilica at a place called Kardia just to the northwest of the byzantine chapel of Faneromeni off the same road to Argos.

A well preserved doric capital survives in a ruined christian chapel near the monastery of Kyra.

The temple of Zeus Meilichos has been located near the church of Agia Triada in Mandraki, where remains of its walls and inscribed stelae were discovered. One nisyrian inscription mentions the cult of Dionysios which, as elsewhere in Greece, would have involved mime reconstructions of Dionysian orgiastic myths.

The arts in ancient classical and hellenistic Nisyros were remarkably advanced; already from the earliest archaic times, Nisyrian potters were producing admirable designs in the most current regional fashions.

Excavations in 1931 executed by the italian archaeological service at the ancient cemetary of Nisyros to the southeast of the acropolis, near the chapel of Agios Iohannis, revealed scores of intact vessels from the 7th to 5th century BC.

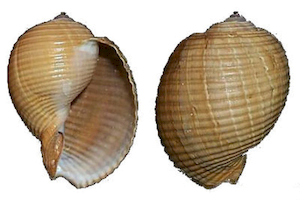

Nisyrians artisans excelled in the delicacy and range of their paintings, which were applied carefully to complement the shape of the vessels; these were typically greek form and execution: ‘oenochoae”, “lekythoi”, “pithoi”, “pinakia”, “stamnoi”, “aryballoi”, “skyphoi”, etc. The earlier painted designs are representative examples of the orientalizing style of the eastern greek world, which adapted images of flora and fauna from Syro-Phoenician art. Soon afterward, Nisyrian workshops began to imitate the subtle designs of “protocorithian” ware, then the well known black and red figure techniques that were established in Athens.

Of the others from the classical and hellenistic period only sculpture and architecture survive sufficiently to give an idea of the quality of workmanship. A tomb excavated in 1953 on the eastern side of the acropolis revealed a fine marble sanctuary bust, 0,34 mt tall, of a young woman, with slightly parted slips, and wearing the ancient chitin on her shoulders.

There is a fragmentary marble funerary stele in excellent condition is housed in the archaeological museum of Istanbul(No. II-1142), showing a standing ephebe, or Nisyrian youth, holding an upright spear.

Other examples of classical Nisyrian sculpture are a superb, though fragmentary marble stele in the Archaeological Museum of Rhodes (No. 72) showing a seated woman in relief, her arms resting on her thighs as the delicately pleated “chiton” she wears is blown across a leg of the chair; beneath the chair is a basket which presumably contained her weaving instruments.

A similar relief on another marble funerary stele and a marble fragment depicting a funerary banquet are now in safekeeping a specially designated area near the Town Hall. The lower marble torso of a standing, chiton-clad man, or god, has stood for years near the ancient terrace walls at Agios Savvas. The work has been variously described as belonging to a cult statue of Poseidon, or the 2nd century BC admiral Gnomagoras, or his near-contemporary, admiral Aristocrates. It is also known from inscriptions that bronze sculptures adorned the agora and sanctuaries.

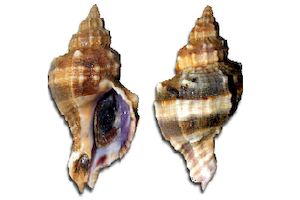

Despite the accomplishments of Nisyrian sculptors, the only artist’s name to have come down to us is that of Epicharmos Soleus. It is likely that other Nisyrian sculptures have found their way into private collections, and are either no longer possible to trace, or to ascribe with certainly to the island’s ancient workshops. In the mid 4th century BC and throughout the hellenistic age, Nisyros produced its own silver and copper coins, which carried images of Poseidon, Artemis, Aphrodite, Apollo and a dolphin with trident.

In architecture, significant changes were introduced after the middle of 5th century BC, presumably prompted by the destructive earthquake that hit Nisyros and Cos in 411 BC; by then greeks were no longer producing buildings styled in the orders associated with their tribal affiliations(Doric, Ionic and Aeolian, etc.). Thus, despite the Dorian ancestry of the Nisyrians, it was no longer usual for temples to be built in a Doric style; the evidence suggests that an Ionic. and Rhodian style came to predominate.

Perhaps the most significant architectural fragments, all of white marble, are an ionic capital in the yard near the old Zosimopouleion The at her in Mandraki(used as a bench seat today) part of a Doric entablature at the place called Kardia to the south of Mandraki,and a Doric capital near the monastery of Kyra on the eastern side of the island. Numerous interesting architectural fragments can be seen in the collection in the Archaeological museum .

A number of marble altar bases with a small scotia molding at the point of juncture with the base are to be seen scattered inside and around the ancient acropolis of Palaiokastro.