After the eruption of the Greek war of independence in 1821 AD, Nisyros took an active part in the insurrection, supplying the fleet of greek admiral Andreas Miaoulis with fighting men prior to the naval battle of Gerontas. In 1821 the Nisyrians helped Miaoulis’ fleet to defeat an Ottoman armada near Cos. Just before this important naval battle, the greek fleet was anchored at the islet of Yiali; there Miaoulis’ sailors a well that is still shown to tourist today.

A document in the monastery of Spiliani in Mandraki, records the initiation of a number of Nisyrians into the “Filikh Etairia”, the secret greek revolutionary society, by the patmian general Dimitrios Themelis.

By 1823, all the islands of the Dodecanese, with the exception of Rhodes and Cos which had strong Ottoman garrisons, were liberated.

They were immediately incorporated into the “Prosorinh Dioikisi ths Ellados”(Temporary administration of Hellas) and organized into “eparchies”(counties).

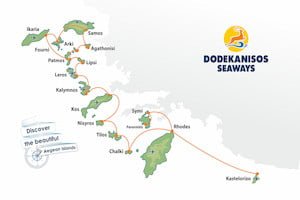

Nisyros now belonged to the Eparchy of Carpathos together with Halki, Symi and Episcopi(Tilos). The greek authorities acted quickly to install officials and initiate the machinery of state. Unfortunately, after the London protocols of March 10 and 22, 1829 and February 3, 1830, the islanders were required, once again, to submit the Ottoman rule; in exchange at this time was more vital to its interests.

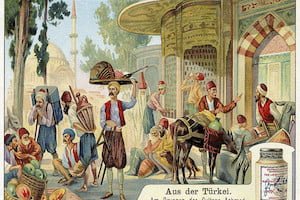

After the brief period in temporary administration, the ottoman governor(vallis) of Rhodes, Mehmet Sükür Bey himself of greek descent(maniot), terrorized then inhabitants with threats, confiscation of properties and imprisonment. After protest by Dodecanesian envoys to the highest authorities in Constantinople, Sükür Bey was replaced, and between 1836 and 1865 the special privileges of the islands were once again respected.

Change in turkish law, however, heralded by the creation of customs buildings on the islands, soon began to alter things. In 1905, the ottoman authorities required all Nisyrians to register births, marriages and deaths. After the “Young turk revolution” in 1908, which causes the collapse of the ottoman empire and the formation of the modern Turkish republic and constitution, the special privileges of the Dodecanese were cancelled and replaced with taxation as elsewhere in the new state. In addiction, young greek men in turkish-controlled territories were now required to serve in the turkish army. Only after vigorous protest did the islanders succeed in exempting themselves from this incompatible and embarrassing requirement.

Turkish rule on Nisyros ended on May 12, 1912, only be followed by 31 years of Italian occupation. This came about a direct consequence of the war that Italy had declared on Turkey in September 1911 for control of strategic north African territories of Cyrenaica and Tripolitana.

When the Turkish government refused to recognize Italy’s annexation of these lands, the Italians made plan to capture a few well-placed Aegean islands in order to block the movement of turkish military supplies to Libya, where the war was in progress.

In April 1912, an Italian fleet under the command of admiral Leone Viale sailed toward the Dodecanese islands. After a brief but intense battle with Turkish troops on May 4th, the Italians succeed in capturing the island of Rhodes, and within two weeks the rest of Dodecanese was under their control.

Though welcomed at first by the natives as liberators, the Italians soon began to transform the islands into permanent colonies. This had not yet been understood by the locals when, on the 18th of June 1912, native representation from each island( N. Petridis for Nisyros) met in Patmos and agree on the formation of an autonomous greek islands state, under the protection of the Italian government, that would pave the way for union with Greece.

Tough the Italian colonial authorities ignored the initiative at home,they used it to advantage their dispute with Turkey, arguing the half-truth that the islanders would never accept to return to the pre-invasion status. The other half of the truth, of course, was that the islanders did not wish to be governed by any foreign power at all.

The greek government was quick to support the Patmos delegates, advising them on a range of issue s from the creation of a transitional governmental mechanism and institution of public services to the nature of the new state’s flag, official emblems, postage stamps, etc.

The impassivity with which the Italian government treated the political desires of the Dodecanese became clear after the signing of the Italo-turkish peace treaty at Ouchy on October 18, 1912, which stipulated that Italy would return the islands as soon as the latter withdrew its troops from Tripolitana and Cyrenaica. As no limit was set for the withdrawal of the Turkish troops, and a guerrilla war was sure o be waged indefinitely in north Africa by islamic militants.

The Vichy agreement was understood by both sides to be a ratification of the new ‘status quo’, which bestowed upon Italy the laurels of military victory without branding Turkey as the loser.

The islanders could do nothing but accept their faith as subject of new foreign master. This became particularly difficult as the greek navy had, in the meanwhile, commenced liberating the northern Aegean islands from turkish rule. Thus, the Italians who had at first been welcomed by the Dodecasians as liberators, came to be regarded with increasing resentment.

In reaction to the negative shift in the disposition of the natives, the first Italian governor , Giovanni Ameglio, set into motion a ogram of demoralization aimed to dissolving the social, political and religious bonds what had permitted the islanders to retain Greek identity through centuries of turkish rule.

After the autumn of 1912, the Italians began to intimidate, arrest, mistreat and exile any native who expressed national sentiments.

At the same time they initiated a drive to lay a historical claim on the islands on the ground that they were continuing the work of protecting them from islamic aggression that had been undertaken by the Knights of St. John in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Books and leaflets exaggerating the Italian ethnic make-up of the mediaeval Knights of Rhodes and justifying their occupation of the islands were distributed fee of charge to the population.

In a carefully disguished effort to lend its propagandistic efforts academic authority, Giuseppe Gerola to survey the ruins of the knights’ fortresses and other monuments around Dodecanese. Though relatively unblased , Gerola’s publications on the subjects were used selectively trump up Italy’s historical rule in the eastern Aegean.

A similar propagandistic attitude was espoused by the authorities with regard to then remains of ancient civilization. In general the numerous italian archeologists who operated in the Dodecanese did so with genuine professionalism. On Nisyros the work of Giulio Jacopi, who unearthed the extensive Archaic and Roman-period cemetary near Agios Iohannis in Mandraki, was in fact exemplary. Yet the policy of the colonial government in Rhodes WS to excavate and restore as many monuments from the Roman and Frankish periods as possible.

In August 1915, Italy once more declared war on Turkey, having just sided with the “Triple Entente” against Austria and Germany. In exchange for its military support, Italy succeeded in having Britain and her allies acceptmits claims to the full sovereign rights in the Dodecanese. In July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne saw the end of the World War I and Turkey permanently cede the islands to Italy. In the nine years that had elapsed since italian takeover, the islanders had grown increasingly defiant, and the Italian troops had on occasion to use the force to regain control.

After the Treaty of Lausanne, the islands entered the third, and most difficult, phase in the italian occupation. The new international recognition of italian rule isolated the islanders and transformed their initial defiance into a full-fledged resistance movement that echoed the greek struggle for independence in the early 19th century. Around Dodecanese, houses were painted the greek national colors,blue ( many abandoned houses on Nisyros still retain their blue hues); stirring patriotic messages were delivered by the clergy, people took to sewing Greeks flag inside their clothes, and anti-italian leaflets and grafitti proliferated.

Under the succesive regimes of governor Mario Lago and Cesare Maria de Vecchi, conte do val Cismon, italian political assertion and colonization reached a frenzied peak. Absurd ‘forest taxation’ law forced Greeks farmers to abandon their lands and flocks, properties belonging to the church and municipalities were randomly ‘nationalizated’; italian banks would not advance money to greek merchants; after 1926 the authorities made it very difficult for Greeks to obtain professional licenses; italian companies monopolized the most profitable industries (only two of eleven shipping companies operating in the Dodecanese were left in greek hands; virtually all the construction companies and hotels were italian-owned).

Meanwhile governor Lago attempted unsuccessfully to force local orthodox church authorities to cede from the patriarchate in Constantinople. The procedure of bestowal of orthodox priesthood was subjected to frustratingly long delays intended to discourage interest( on Cos after the death of the metropolitan bishop, Agathangelos Archytas, in 1924, no less than 23 years passed before his successor Emmanouil Karphathios was installed).

A serious blow was dealt to the islanders’ pride when, with the “Ordinamento delle scuole elementari e medie” of 1926, governor Lago made the italian language compulsory in all grades of school, and prescribed biased and propagandistic textbooks. Greek was finally denigrated to the status of ‘lingua locale’ , or ‘religion tongue’, by De Vecchi in 1937, and left only as an optional course. Greek textbooks were entirely withdrawn, and a course entitled ‘Cultura Fascista’ was introduced.

Only degrees from Italian universities were recognized in the Dodecanese and greek students interested in advanced studies were sent to the university of Pisa where their activities could be monitored by the italian secret service. The injustice of the italian intervention in education is immediately evident, when the relative ethnic population of the Italians occupied Dodecanesian islands are compared: in 1935 the italian numbered a mere 7,000 colonists, 550 state employees and about 7,000 troops out of a total population of 132,638 inhabitants.

Architecture played a vital role in the forced process of italianization of the Dodecanese . Until 1912 the island towns were characterized by simple vernacular residences with straight forward, in cumbersome constructional details that had remained unchanged for millennia, and more monumental churches and civil buildings Italian architects began to apply monumental expressions indiscriminately, with the results that hotel buildings, apartment block , houses and other private structures were often just as elaborately treated as the public buildings. This had the effect of ‘ over changing’ the urban context, and confusing the clear civic hierarchies of Dodecanesian town.

The search of a proper colonial expression by the italian took on a number of aspect: in the first half of the occupation it was either an ecclectic synthesis of the various monumental traditions present in the broader region, or a straight imposition of traditional and classical italian forms.

The fascist government of Mussolini in the 1930s and 40s favored an architecture either of stripped-down, over scaled classicizing architectural forms, designed to convey the regime’s deterministic manipulation of conventions, or a ‘progressive’ international style modernism that projected the technocratic aspirations of the new 20th century authoritarianism.

The colonial enthusiasm of the Italians was such that, no matter how competent the work of their architects might have been, it could hardly avoid appearing contrived or revisionist, and therefore alien.

As former Ephor of Dodecasian antiquities Grigorios Konstantinopoulos has said, ultimately even the various hybrid arabesque and italic forms of the first phase of italian occupation were “… drawn out of the clean-slate intellectual archirectural attitudes of the German Bauhaus and international modernism, these forms heralded the coming of fascist regimes, permitting the conception and construction of governmental and public buildings for the new cities of an italian empire…”.

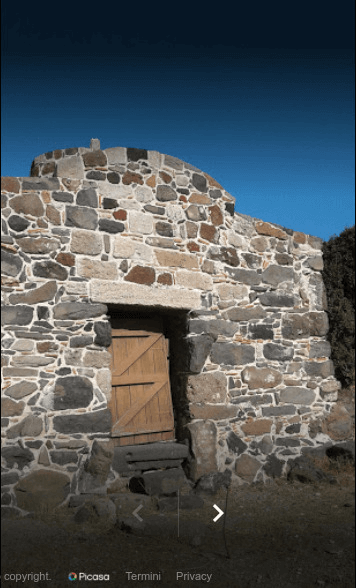

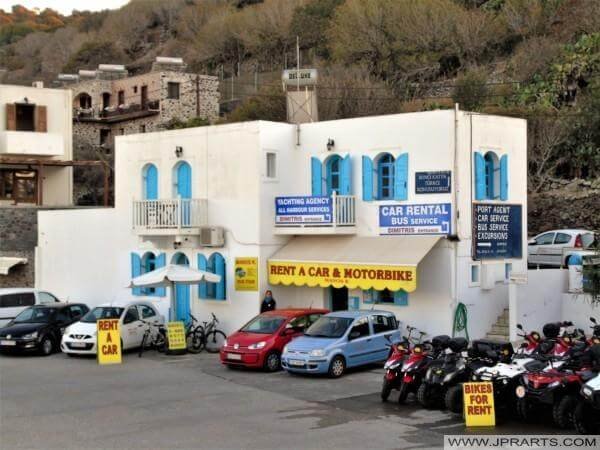

Despite their formal strangenesses, many few new colonial buildings were nevertheless meticulously executed in local materials and with reliable traditional techniques that were designed to allow the buildings to last for generations. The ‘Caserma’ at the port of Mandraki on Nisyros proves just that, having been used continuously since its construction in 1935; it currently houses the greek port authority and the police headquarters. Until the occupying force’ colonial intentions became apparent in the mid 1930s, many new Nisyrian buildings were characterized of a hellenic culture after four centuries of ottoman rule.