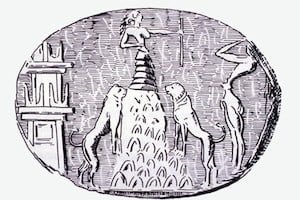

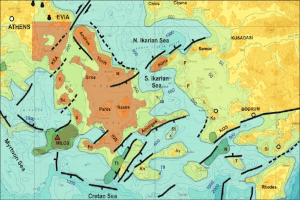

Sometime between 1,100 and 1,000 BC, a new wave of Greeks, the Dorian’s, swept into the mainland and Peloponnese from the north, overrunning and destroying the weakened Mycenaean kingdoms, then continuing on to Crete and Aegean islands. From Diodorus Siculus we learn that upon reaching the Cycladic islands the Dorians expelled recent Carians settlers who had taken advantage of the political and social vacuum that emerged after the Trojan War to re-occupy the lands that their ancestors had colonized more than a millennium previously.

The same is likely to have occured on Nisyros and the other southeastern Aegean islands. Having established themselves across Greece in the former Mycenaean territories, the Dorians subsides for about two centuries in a primitive manner. The arts that had flourished in the age of king Atreus and Agamemnon were almost entirely forgotten, the great aristocratic families and lineages remembered chiefly through the cycle of epic poems that were passed down from generation to generation until Homer adapted and committed them to posterity in writing.

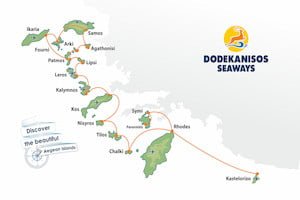

Herodotus identified the 5th century BC inhabitants of Halicarnassus as Dorians from Troizen, and inhabitants of Cos, Nisyros and Calymnos as Dorians from Epidaurus in the Peloponnese. Whether the Dorians mingled peacefully or came into conflict with the Mycenaeans or the more recent Carian setllers on Nisyros is unknown to us.

Certainly the historical identification of the island as Dorian indicates that the newcomers took complete control of it, either through the strength of their numbers or military action.

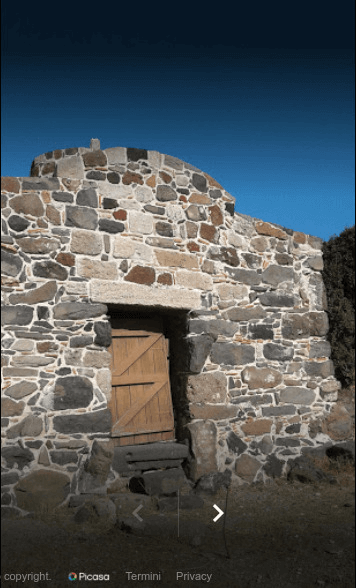

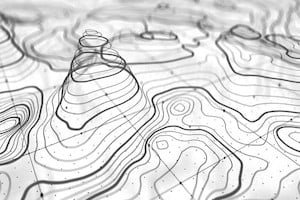

It is possible that the massive rubble fortification walls visible on a plateau to the east of the monastery of Panagia Kyra were erected by a Dorian expeditionary force seeking to control the island’s only source of drinkable water (at the nearby site of Pigi), and making use of the beach at Pachia Ammos as landing site, or alternatively by Mycenaeans attempting to hold that front; the marble Doric capital that has been found in the ruins of a Christian chapel near the monastery may have belonged to a temple built by descendant of the intruders.

The Dorians who settled the south Aegean maintained close political and cultural links with each other. By the early archaic period they had formed what they termed the “Dorian Hexapolis”, an alliance based on a shared ethnicity, which consisted of the three older towns of Rhodes(Lindos, Ialyssos and Cameiros), and the cities of Cos, Cnidos and Halicarnassus. Dorian Nisyros came to be regarded as a partner in the Hexapolis.

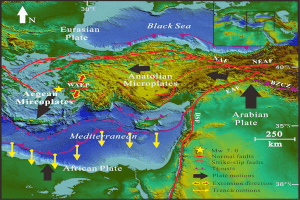

Toward the beginning of the 7th century BC, king Gyges of Lydia succeeded in subduing the Greek cities in Asia minor and islands its coast, including Nisyros.

Being a philhellene, however, he was quick to appease his new subjects, basing his control on the collection of a small tributary tax that had symbolic, rather than political, value. The eastern Greeks were therefore free to pursue their commercial and cultural ambitions, prospering and extending their influence over the entire greek world. At the same time they tolerated the Lydians, who acted as guarantors of their safety and benefited from their subjects’ commercial growth.

On Nisyros the transition from the Mycenaean feudal system that was overthrown by the descent of the Dorians appears to be complete, for, unlike some other cities in post-mycenaean Greece, there is no indication, historical, epigraphical or otherwise, of the survival of an aristocratic element of the society. As the island emerged in the 8th century BC from more than two centuries of obscurity, a democratic political system had taken firm root, in which the “demos”(citizenry), involved itself directly with political cultural and economic decision making.

During the Persian Wars, Nisyros fought on the side of king Xerses under the command of queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus at the battle of Salamis, in 480 BC.

After the formation of the Delian League, Nisyros became a tributary ally of the Athenians, contributing troops and funds during the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) until the victory of Sparta at Agios Potamoi, in 405 BC. For a period of 11 years, Nisyros, like the other islands, sided with the victorious Sparta, until the battle of Cnidos, 394 BC, which would have been clearly visible from the island, when the Athenian admiral Conon temporary re-established his city’s hegemony in the area.

Nisyros, which during most of the 4th and 3rd century BC, appears to have operated as a fully independent city-state, signed a peace treaty between the warring greek city states, 371 BC, becoming once again an Athenian ally. Shortly afterward, however, it was persuaded by its regional allies Cos and Rhodes, as well as the half-greek Carian king Mausolos, to rebel against Athens. Mausolos, who despite styling himself king, was in fact no more that a Persian satrap, took advantage of the apostasy and occupied Cos, Rhodes, and the other islands near the Carian coast. Thus Nisyros can be said to have briefly returned to the Persian fold. After Mausolos’ death, his wife Artemisia(like the queen of Halicarnassus) replaced him as sovereign until her death in 350 BC.

Nisyros subsequently regained its status as an independent city-state; after the battle of Chaironeia, 338 BC, king Philip of Macedon succeeded in uniting the greek world, forming the ‘League of Corinth’, and in 337 BC declared war on Persia to avenge continuing Persian aggression against subject Greek states.