According to ancient mythographers, Nisyros was created by the god Poseidon during his battle with the giant Polyvotis, whom he pursued until he came to the island of Kos. Using his trident to break off and hurl a fragment of Kos, Poseidon crushed Polyvotis under the rock’s weight. That rock, the myth says, is Nisyros. The island has been inhabited since Neolithic times. A Cycladic figurine now in the Berlin Glyptothek is said to come from Nisyros, and a later Minoan presence is confirmed by the discovery, at the Palace of Zakros in Crete, of a beautiful chalice made of a single piece of obsidian from the island of Yiali, adjacent to Nisyros.

The earliest written mention of the island occurs in Homer’s “Iliad” (8th c. BC), in which we learn that Nisyros contributed ships to the expedition against Troy (1184 BC), under the command of the rulers of Kos, Pheidippos and Antiphos. Soon after the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, Nisyros appears to have been overrun by a new wave of Greeks from the mainland, the Dorians. The ancient historian Herodotus identified the 5th c. BC inhabitants of Kos, Nisyros and Calymnos as Dorians from Epidauros in the Peloponnese. The colonists who settled in the southeastern Aegean formed a “Dorian Hexapolis,” of which Nisyros was regarded as a partner. By this time, Nisyros had at least one town, a harbor, thermal baths, and a temple dedicated to Poseidon. The city was located in the area of the modern town of Mandraki, beneath the ancient acropolis of Palaiokastro.

During the Persian Wars, Nisyros fought on the side of King Xerxes and took part, under the command of Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus, in the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. After the formation of the Delian League, Nisyros became a tributary ally of the Athenians, contributing troops and funds during the Peloponnesian War. Following the victory of Sparta at Aigos Potamoi in 405 BC, the island briefly joined the Spartan side, until the Battle of Cnidos in 394 BC, when the Athenian admiral Conon temporarily re-established his city’s hegemony in the area.

The history of Nisyros dates back many centuries in the past. Traces of Neolithic settlements have been found on the island, older than the 5th millennium B.C. Evidently, inhabitation of Nisyros through modern times has continued without interruption since then. The island was particularly booming in the 4th century B.C. as well as the 12th-13th century A.D.

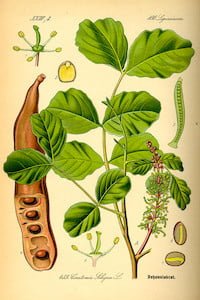

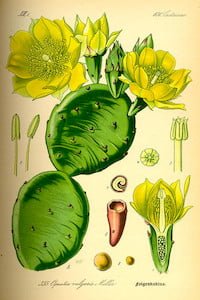

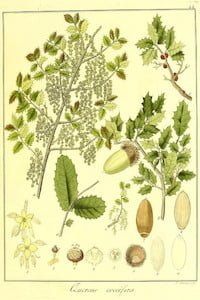

Farming produce (almonds, figs, acorns, grapes, olives), fishing and cattle breeding activity (goats, oxen, pigs) no longer suffice. Thus, inhabitants resorted to emigration, first to Alexandria, Smyrne and Constantinople and later to America and Australia. Moreover, several locals have rushed to Athens since 1930 and later to Rhodes.

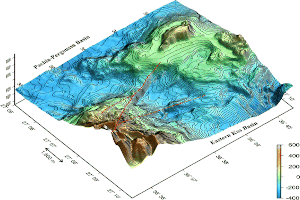

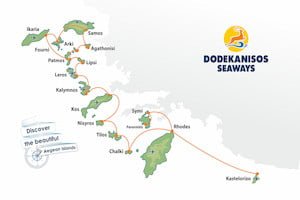

Nisyros, with an approximate area of 42 sq. km, is one of the smallest islands of the Southern Sporades or Dodecanese. Dodecanese is a name first employed to indicate those islands granted benefits by Suleiman the Magnificent, following the surrender of Ioannite knights (Hospitallers) to the Ottomans in 1522.

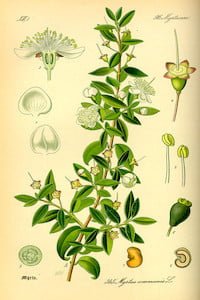

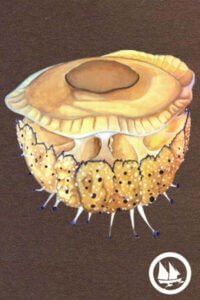

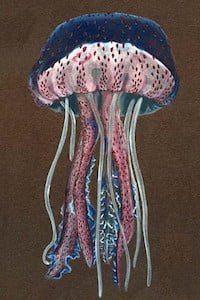

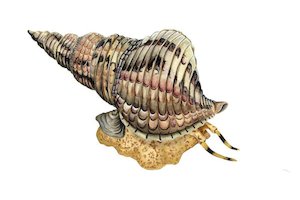

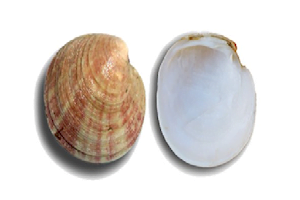

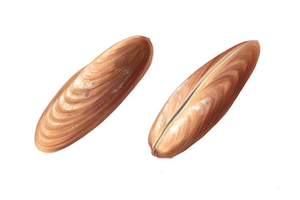

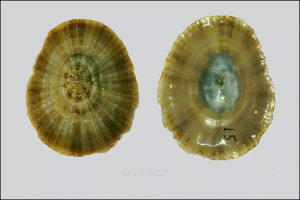

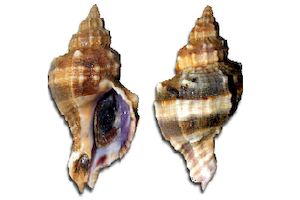

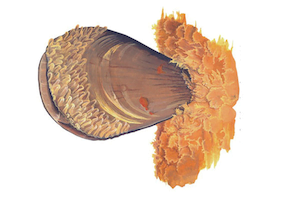

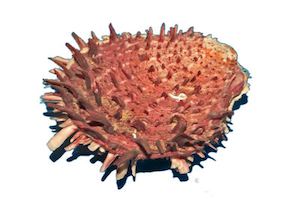

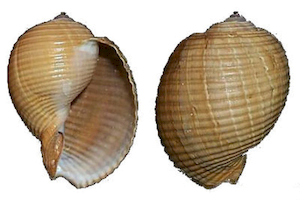

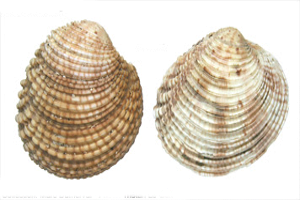

The island’s name is probably rooted in the ancient Greek words “neo (νέω, to swim)” and “syro (σύρω, to drag)” thus linking the island’s name to its legendary creation by Poseidon, after having clashed with giant Polyvotis. In another version, it originates from words “nies (νήες, ships)” and “syro (σύρω, to drag)”, meaning ships thrashing into the sea. A last version calls for an alleged corruption of “nea Saros”, a name possibly bestowed by Kares (pre-hellenic Cretans) who colonized both Saros (an island north of Karpathos) and Nisyros. In ancient times, Nisyros was also known as “Porphyris”, possibly owed to the production of laver from murex shells or owed to the production of tools (mainly grindstones) from ‘porphyrite’ stone (lava blocks). The Ottomans used the word ‘Intsirli’ as the island’s name (island of figs).

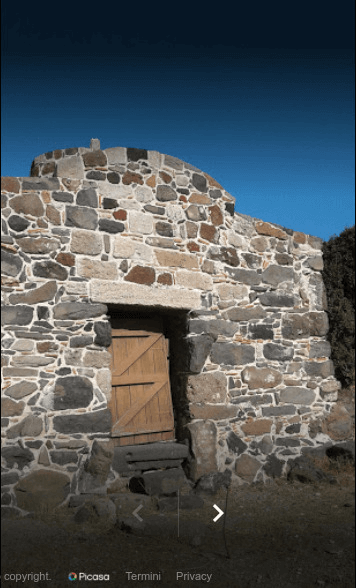

Despite their limited size, Nisyros and the surrounding islets host monuments of particular interest and historic value.

The oldest evidence of human presence in the greater area belongs to the Neolithic age, with remains of inhabitation in Yali (the ancient Kissiris) and at certain locations mainly in northwest Nisyros.

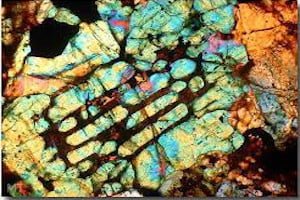

There are scant traces of Minoan and Mycenaean presence, evidenced by horn-shaped carvings, vessel fragments and ‘cyclopean’ walls characteristic of these civilizations found in Nisyros. The island’s relevance to pre-Hellenic Crete is mainly demonstrated by an ornamental cup made from Yali obsidian, found in the Cretan palace of Zakros.

The pre-classical and classical periods (10th to 4th century B.C.) are mainly represented by the profound Paleokastro, several sculptures and extracts from ancient temples used in paleochristian churches, and communities found on the Argos site, as well as traces of inhabitation and vases from the same period in adjacent Yali, Pyrgoussa and Pahia.

The remains of the Hellenistic period are some extensions and additions to classic structures, as well as numerous surveillance towers (‘Friktoria’) both in Nisyros and Pyrgoussa, evidently named after such towers (Pyrgos = tower).

The Roman period left sculptures and remnants of baths and cisterns; remnants of the latter remain intact close to Pali.

In the early Byzantine times, several large and small churches were built; the ruins of some of them are still intact.

No proven traces of civilization are found on the island from the period between 7th and 10th centuries A.D.

The Latin nations prevailed on the island between the 11th and 15th century, initially Venetians and later Ioannite knights, the latter having built the Castle of the same name in Mandraki (Kastro) as well as several other entrenchments.

After the fall of Constantinople, Nisyros was left defenseless to raids by pirates and the Turks; by the late 15th century the island had been entirely depopulated and in 1522 it surrendered to the Turks; the latter occupied the island until 1912, when it was annexed by Italy. A special regime was granted to the Dodecanese islands by the Ottomans, granting strong and vigorous self-government, which enabled Nisyros to achieve significant growth in this period. The rather prosperous and intense social activity is evidenced by the numerous churches from this period.

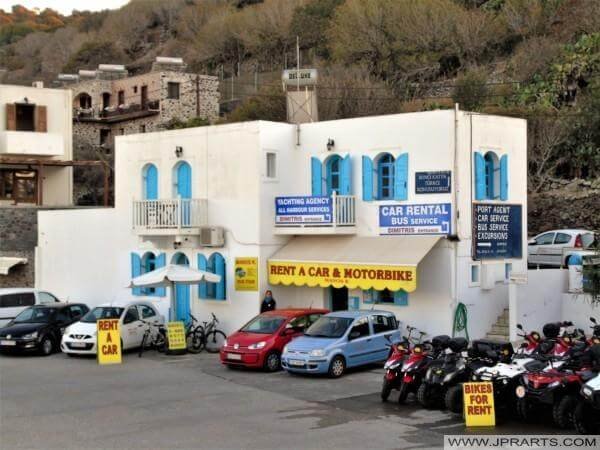

The efforts to ‘Italianize’ the Dodecanese are evident in monuments on Nisyros from the presence of Kazerma at the Mandraki harbor (the harbor was constructed in 1885 in its present position).

By the end of the 19th century it was populated by around 5,000 inhabitants. The decline of the island started ever since.